Lady Gregory's Toothbrush (2 page)

Read Lady Gregory's Toothbrush Online

Authors: Colm Toibin

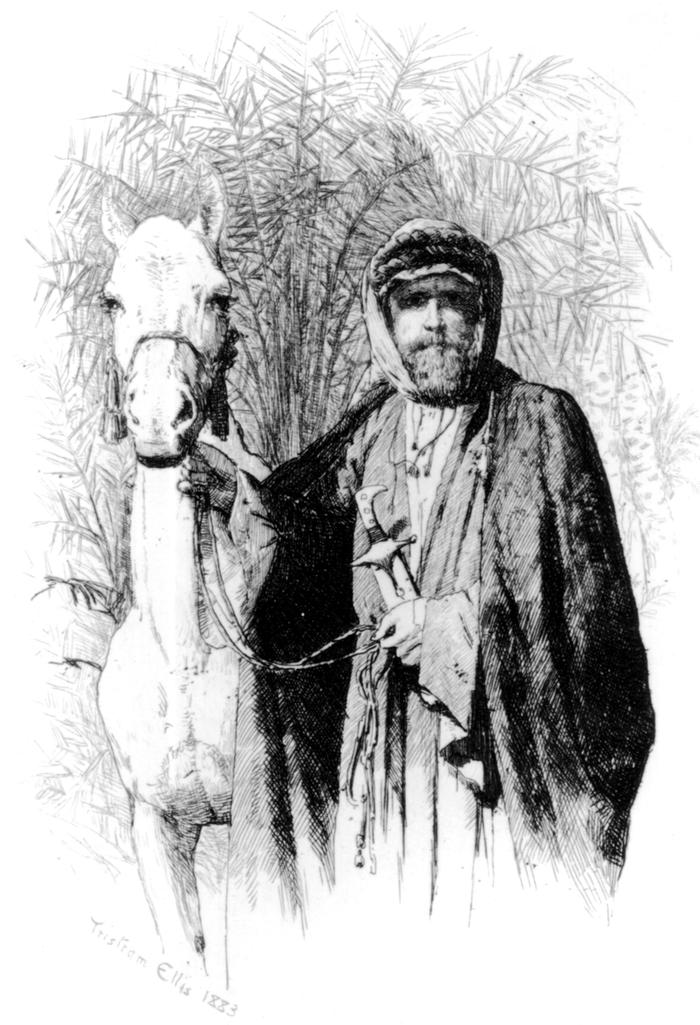

Her sonnets make clear that she was in love with him and that she had an affair with him which began during their Egyptian sojourn, when she had been married for less than two years, and ended eighteen months later. Her image after Sir William's death was that of a dowager who exuded dryness and coldness and watchfulness, who wore black and modelled herself on Queen Victoria. The

sonnets

, on the other hand, disclose someone else:

If the past year were offered me again,

And the choice of good and ill before me set

Would I accept the pleasure with the pain

Or dare to wish that we had never met?

Ah! Could I bear those happy hours to miss

When love began, unthought of and unspoke â

That summer day when by a sudden kiss

We knew each other's secret and awoke?

In these twelve poems she was in the sweet position of disclosing the love which had to remain secret:

Pleading for love which now is all my life â

Begging a word that memory may keep,

Asking a sign to still my inward strife,

Petitioning a touch to smooth my sleep â

Bowing my head to kiss the very ground

On which the feet of him I love have trod,

Controlled and guided by that voice whose sound

Is dearer to me than the voice of God.

Very few of the changes Blunt made to the poems improved them; he tended to soften her directness and dull her precision. But he could do nothing to lessen the sense of loss and shame in some of these poems, which are quoted here in her versions:

Should e'er that drear day come in which the world

Shall know the secret which so close I hold,

Should taunts and jeers at my bowed head be hurled,

And all my love and all my shame be told,

I could not, as some women used to do

Fling jests and gold and live the scandal down â

I could not, knowing all the story true

Hold up my head and brave the talk of town â

I have no courage for such tricks and ways,

No wish to flaunt a once dishonoured name â

Have still such memory of early days

And such great dread of that deserved shame

That when it comes, with one all hopeless cry,

For pardon from my wronged ones, I must die.

Â

T

he ten years in Lady Gregory's life between the death of her husband in 1892 and the first performance of

Cathleen Ni Houlihan

involve what is ostensibly a complete transformation in her life. A landlord's daughter and widow, steeped in the attitudes of her class, she became an Irish nationalist and leader of a cultural movement that was more powerful than politics. But her activities in these ten years also displayed what would, for the rest of her life, range from ambiguities to deep divisions in her loyalties and her beliefs. In 1893, for example, she published in

London

an anonymous pamphlet called

A Phantom's Pilgrimage

or Home Ruin,

essentially a piece of pro-unionist rhetoric, in which Gladstone returns from the grave ten years after Home Rule to find that every class in Ireland has suffered dire consequences. Later that year she travelled alone to the Aran Islands, staying in a cottage in Inishere “among people speaking scarcely any English”. She wrote to

English

friends about the trip and her reading of Emily

Lawless's

novel

Grania

, set on the islands, and Jane Barlow's

Irish Idylls

, stories of Irish peasant life. (“I look on it as one of my Irish sermon books; it really gives me sympathy with the wants of the people.”) In the meantime, she worked on her husband's incomplete manuscript for his

Autobiography

.

While this work seemed to Wilfrid Scawen Blunt merely a widow's “pious act”, and had very many dull moments and displays of Sir William's self-importance

and vanity, it was at the same time a piece of careful

repositioning

and re-invention which would become the basis not only for Lady Gregory's life at Coole and her work with Yeats, but also for many of Yeats's poems about Coole and many of his Anglo-Irish attitudes. It would emphasize, as in her account of Sir William's funeral, that he was loved by the people, that he and his family were respected as landlords. She would insist upon this all her life. In her own conclusion to the book, she quoted from a letter he had written to her “just before our marriage”: “I always felt the strongest sense of duty towards my tenants, and I have had a great affection for them. They have never in a single instance caused me displeasure, and I know you can and will do everything in your power to make them love and value us.” She continued: “He was glad at the last to think that, having held the estate through the old days of the Famine and the later days of agitation, he had never once evicted a tenant. Now that he has put his harness off I may boast this on his behalf. And, in the upheaval and the changing of the old landmarks, of which we in Ireland have borne the first brunt, I feel it worth boasting that among the first words of sympathy that reached me after his death were messages from the children of the National School at Coole, from the Bishops and priests of the

diocese

, from the Board of Guardians, the workhouse, the convent, and the townspeople of Gort.” In a letter to a

friend of his in London composed while she was working on the manuscript, she wrote: “I attach great importance to the breadth and sincerity of his views on Irish questions being remembered.”

This note would surface again and again in her letters and diaries. As late as 1920, when she was negotiating the sale of land at Coole, she wrote to Sir Henry Doran of the Congested Districts Board: “May I draw your attention to the fact that through all the troublesome times of the last forty years we have never had to ask compensation from the County or for police protection. We have been, in comparison with many other Estates, a centre of peace and goodwill. This was in part owing to the liberal opinions and just dealing of my husband and my son.”

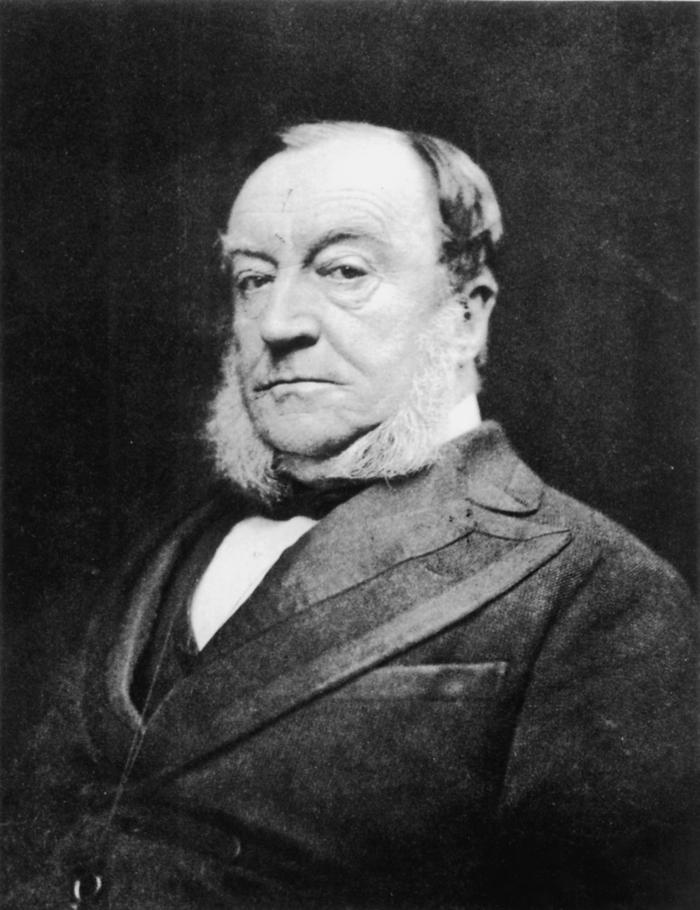

In the table of contents for Sir William's

autobiography

, Chapter V11 contains a section entitled “The

Gregory

Clause”. Sir William devoted two and a half pages to the subject, most of it a quotation from an article published in the

Dublin University Magazine

in 1876 that attempted to justify the Gregory Clause, which was passed by the House of Commons in March 1847.

Sir William Gregory was one of a large number of Irish landowners and politicians who took the view that the

system

of land-holding that had been in place in Ireland before the Famine could not continue. They believed that there were too many smallholdings and too many tenants.

In 1848, Lord Palmerston, for example, wrote to Lord John Russell: “It is useless to disguise the truth that any great improvement in the social system of Ireland must be founded upon an extensive change in the present state of agrarian occupation, and that this change necessarily implies a long, continued and systematic ejectment of small holders and squatting cottiers.” During the first two months of 1847, in the House of Commons debates on the famine in Ireland, Sir William Gregory had argued against the system of relief being used. He supported the idea of assisted emigration. He also proposed an amendment to the Poor Law Act in March 1847 that was to have

far-reaching

implications. The clause stipulated that no one who held a lease for more than a quarter of an acre of land should be allowed to enter the workhouse or to avail of any of the relief schemes. This meant that a cottier tenant whose potato crop had failed a second year in succession and who had no money to buy food would be faced with a stark choice. If he wanted to take his family into the

workhouse,

the only place where they could be fed, he would have to give up his lease and he would never get it back. His mud cabin would be razed to the ground as soon as it was empty. If he and his family survived the workhouse, where disease was rampant, they would have nowhere to go. They would have to live on the side of the road, or try to

emigrate

. Nor could a man send his wife and children into the

workhouse and stay on the land himself. They could get no relief unless he gave up the lease. “Persons”, Sir William said in the House of Commons, “should not be encouraged to exercise the double vocation of pauper and farmer.”

In his autobiography, Sir William quotes the

Dublin

University Magazine

article from 18 to justify himself: “That this clause has been perverted to do evil no one can deny, and those who only look to one side of the question have often blamed its author for some of the evils that were inflicted by its provisions ⦠The evil results we have alluded to were not foreseen, certainly they were not believed in by Mr Gregory, whose advocacy of the

emigration

clause is the best proof of his good motives to those who do not know the humanity and the kindness which, then and always, have marked his dealing with his tenants on his own estates.”

The effects of the clause, however, were foreseen by those who voted for it in the House of Commons on the night of 29 March 1847, as well as by the nine MPs who voted against it. Sir William's proposing speech was

followed

by William Smith O'Brien, who was reported as saying: “If a man was only to have a right to outdoor relief upon condition of his giving up his land, a person might receive relief for a few weeks and become a beggar for ever. He thought this was a cruel enactment.” Another speaker in the same debate said that the consequence of Sir

William Gregory's clause “would be a complete clearance of the small farmers of Ireland â a change which would amount to a perfect social revolution in the state of things in that country ⦠to introduce it at once would have the effect of turning great masses of pauperism adrift on the

community.” Hansard reported that Mr Bellew, speaking in support of the clause, argued that it “would tend to the gradual absorption of the small holdings now so

extensively

held, as well as the conversion of masses of starving peasantry into useful and well-paid labourers”. And Sir G. Grey in the same debate said that he “had always

understood

that these small holdings were the bane of Ireland”.

In his autobiography, Sir William wrote: “There is no doubt but that the immediate effect of the clause was severe. Old Archbishop MacHale never forgave me on account of it. But it pulled up suddenly the country from falling into the open pit of pauperism on the verge of which it stood. Though I got an evil reputation in consequence, those who really understood the condition of the country have always regarded this clause as its salvation.”

The Gregory Clause radically reduced the number of small tenants. Roughly two million people left Ireland

permanently

between 1845 and 1855, according to the historian Oliver MacDonagh, who also wrote: “The cottier class had virtually disappeared. The number of holdings under one acre had dropped from 134,000 to 36,000 ⦠the

number

of persons per square mile ⦠had fallen from 355 to 231; and the average productivity had risen greatly. In short, the modern revolution in Irish farming had begun.”

Sir William's father died of fever during the Famine, and he himself witnessed the suffering around Coole and

wrote about this in his book. “I did ⦠all I could to

alleviate

the dreadful distress and sickness in our

neighbourhood

. I well remember poor wretches being housed up against my demesne wall in wigwams of fir branches ⦠There was nothing that I ever saw so horrible as the appearance of those who were suffering from starvation. The skin seemed drawn tight like a drum to the face, which became covered with small light-coloured hairs like a gooseberry. This, and their hollow voices, I can never forget.” In April 1847, four thousand destitute labourers gathered at Gort, the nearest town to Coole, looking for work. A year later, a Poor Law inspector wrote that he could scarcely “conceive a house in a worse state or in greater disorder” than the workhouse in Gort. A quarter of the population in the area sought relief in those years.