Killing Jesus: A History (12 page)

Read Killing Jesus: A History Online

Authors: Bill O'Reilly,Martin Dugard

Tags: #Religion, #History, #General

Of course, should Thrasyllus fail Tiberius, whether through bad information or willful manipulation, his long fall into the sea will be no different from that of the young sex slaves.

For Tiberius learned long ago that no one can be trusted. He was born two years after the death of Julius Caesar, whose name has been incorporated into his own. When his mother divorced his natural father to marry the man who would one day be known as Augustus, the three-year-old Tiberius actually benefited from the betrayal. The Roman emperor soon adopted him as his own son, and Tiberius rode through the streets of Rome in Augustus’s chariot during the public celebration marking the crucial victory over Marc Antony and Cleopatra.

The boy grew up privileged, trained in the classical manner, excelling in oratory and rhetoric. By age twenty, he was commanding armies. A brilliant tactician and fearless fighter, Tiberius was known for his successes on the battlefield—but also for his dark and gloomy behavior and the severe acne covering his face. Upon his return to Rome, he found love and married a young woman of noble birth named Vipsania. They had a child, Drusus Julius Caesar, after which Vipsania was soon pregnant with a second baby. But Augustus cruelly intervened. In an act that would dramatically transform Tiberius, the self-proclaimed son of god ordered Tiberius to divorce Vipsania after eight years of marriage and wed Augustus’s recently widowed daughter, Julia. When Tiberius argued against the divorce, he was ordered to be compliant or suffer harsh punishment. Devastated, Vipsania suffered a miscarriage.

Tiberius was distraught but obeyed the emperor. A short time later he accidentally ran into his beloved Vipsania on the streets of Rome and broke down, making a very public display by sobbing and begging for forgiveness. When news of this behavior reached Augustus, he demanded that Tiberius never again speak with Vipsania.

And so died the human part of Tiberius. At that moment, his life of cruelty, depravity, and drunkenness began. The man who once studied rhetoric and who loved the mother of his child was emotionally destroyed. Never again would he act in a humane manner. But his behavior didn’t bother his new wife, Julia, who herself embraced debauchery. She had a fondness for dwarves, and when Tiberius once again marched off to war—this time in Gaul—she kept such a man nearby at all times for her immediate pleasure. Julia was a great beauty, which made it easier for her to indulge her base instincts. She attended orgies, openly prostituted herself, and publicly flaunted her disregard for Tiberius. Most grievous of all, when Tiberius returned from Gaul, he found that she had turned their home into a brothel.

Emperor Tiberius

Even Augustus was appalled. He granted Tiberius a divorce. But the man who would one day be emperor would never marry again.

Deeply shamed, Tiberius, approaching forty years old, exiled himself to the Greek island of Rhodes. There he began to drink in ever-larger quantities and established a pattern of cruel behavior that he would embrace to the day he died. He routinely committed murder, even ordering the decapitation of a man whose only crime was making a poor mathematical calculation.

In the final years of his reign, Augustus recalled Tiberius from Rhodes, grooming him to become emperor. There was no other suitable prospect. Tiberius accepted the challenge in willing and ruthless fashion. After Augustus died in

A.D.

14, Tiberius ordered the execution of any would-be pretender. For twelve long years, Tiberius did battle with the Senate and oversaw the empire in a proficient, workmanlike manner. But upon the sudden and unexplained deaths of his adopted son Germanicus

1

and natural-born son Drusus,

2

ages thirty-three and thirty-four, respectively, Tiberius could take no more.

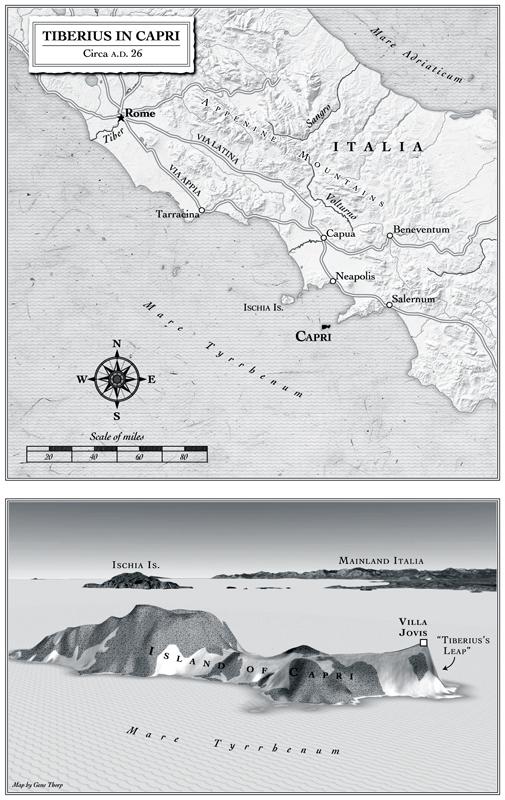

Fed up with the intrigues of Rome, Tiberius ordered that renovations and enhancements be made to Augustus’s villas on the island of Capri. This included the construction of “lechery nooks” and the special pools in which he now swims naked with young boys. His servants are authorized to kidnap children, and Tiberius even employs a man known as “Master of the Imperial Pleasures,” whose sole job is providing the emperor with new bodies.

In the midst of all this, Tiberius continues to hold control of the vast Roman Empire. From high on a mountain, safe from assassination plots, and surrounded only by those he can murder on a whim, Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus issues the moral and legal decrees that will determine the fate of millions. Those mandates especially affect Roman administrators.

Pontius Pilate, newly installed as Roman governor of Judea, knows that his personal and professional future depends on making the degenerate Tiberius happy. Despite his own pagan lifestyle, Tiberius admires the Jews’ religious ways. He considers the Jews the most devout subjects in the empire when it comes to keeping the Sabbath holy. Tiberius sends an order to Pontius Pilate on how to treat the Jewish population: “Change nothing already sanctioned by custom, but to regard as a sacred trust both the Jews themselves, and their laws, which are conducive to public order.”

So it is that Pontius Pilate honors that “sacred trust” by strengthening his bond with the high priest Caiaphas, the figurehead of the Jewish faith and the most powerful man in Jerusalem. According to Tiberius’s orders, Pilate is not to meddle in matters of Jewish law.

It is an order that Pilate will remember all too well.

* * *

Herod Antipas, now approaching fifty, understands that allegiance to Tiberius is vital. He has spent a great deal of time in Rome, educating himself in Roman ways and customs and absorbing Romans’ fondness for literature, poetry, and music. The Jew Antipas even dresses like Roman aristocracy, wearing the semicircular piece of cloth known as a toga rather than the simple robes of the Jewish people.

During his time in Rome, Antipas learned to douse his food with fermented fish sauce, a pickled condiment favored by Romans with a strong taste that masked spoilage from lack of refrigeration. He attended chariot races at the Circus Maximus. He might even have taken a slave for a lover. In Rome, prostitution is legal and even taxed. The only shame was for a male citizen of Rome to be the submissive partner in a homosexual relationship, which was why Julius Caesar’s long-rumored affair with the king of Bithynia was never forgotten by his enemies.

Antipas has great power over the Jewish peasants, but he must do as Rome tells him to do. He can never comment negatively on anything Tiberius does—even though the Jews are every day becoming more disenchanted with Roman rule. His fear of Tiberius also prevents Antipas from making any reforms that would help the Jewish people. Caught in the middle, Antipas keeps his mouth shut and accumulates as much wealth as he can.

* * *

The Roman Empire may be vast, but all those roads built by the legions, and all those shipping lanes plied daily between Rome and her many outposts, mean that rumors travel fast. Household servants gossip, and word has spread about Tiberius’s aberrant and violent behavior. He murders at will, killing entire families for any perceived slight. He defiles even the youngest child. He retaliates against any woman who will not have him—even a woman of noble birth and marriage—by letting his servants violate her.

But Antipas is not Tiberius. The ruler of Galilee has many faults, among them vanity and personal weakness, but his behavior is nothing like that of the emperor of Rome. Yet the moral depravity of Tiberius cannot help but seep into the fiber of even the most far-flung province, causing an erosion of discipline and justice. While the emperor will never make his way to Judea and never come face-to-face with Jesus of Nazareth or with the Passover pilgrims who flock to Jerusalem each year, every decision ordered by the new Roman governor Pontius Pilate is made to gain Tiberius’s approval. It is the same with Antipas, as evidenced by his naming his dazzling new city on the Sea of Galilee after the all-powerful emperor.

Such is life in the Roman Empire, which has begun its slow decline into ruin. There is little justice or nobility among the ruling class. And so the Jewish peasants look for a savior, a man promised to them by the prophets. For a time, some thought the savior might be John the Baptist. But he languishes in prison.

Now there is cautious conversation about a new man, one far more powerful than John. Jesus of Nazareth is about to arrive.

CHAPTER EIGHT

JERUSALEM

APRIL, A.D. 27

DAY

Jesus clenches a coiled whip in his fist as he makes his way up the steps to the Temple courts. Passover pilgrims surround him. Hundreds of thousands of Jewish believers have once again traveled a great distance—from Galilee, Syria, Egypt, and even Rome—to celebrate the climax to the Jewish year. Not that they have a choice: failure to visit the Temple during Passover is one of thirty-six transgressions that will result in the holy punishment of

karet

, being spiritually “cut off” from God. Those who transgress will suffer a premature death or other punishment known only to the deity.

1

So, as he has done every spring since childhood, Jesus of Nazareth has made the trek to Jerusalem.

The spiritual emotion that flows through the city is wondrous, as these many Jews come together to openly celebrate their faith and sing praises to God. Agents of the Temple have repaired the dirt roads coming into town to make them smooth after the hard winter rains. Grave sites are clearly marked, so that no pilgrim will inadvertently suffer impurity by touching one. Special wells are dug so that every man and woman can immerse him- or herself in the ritual bath, in order to be pure upon entering the Holy City.

Mikvot

(purification pools) are carved into the bedrock and lined in plaster, into which an observant pilgrim steps down for cleansing.

Jesus himself submerges himself in a

mikvah

as a last stop before Jerusalem. Inside the city walls, he sees the hundreds of temporary clay ovens that have been constructed in order that each pilgrim will have a place to roast his Passover sacrifice before sitting down to the evening Seder feast. He hears the bleat of sheep as shepherds and their flocks clog the narrow streets, just down from the hills after lambing season. And Jesus can well imagine the peal of the silver trumpets and the harmonious voices of the Levite choir that will echo in the inner courts of the Temple just moments before an innocent lamb is slaughtered for the Passover sacrifice. A priest will catch its blood in a golden bowl, then sprinkle it on the altar as the lamb is hung on a hook and skinned. The Hallel

2

prayers of thanksgiving will soon follow, and the Temple courts will echo with songs of hallelujah.

This is Passover in Jerusalem. It has been this way since the rebuilding of the Temple. Each Passover is unique in its glory and personal stories, but the rituals remain the same.

Now, as he steps into the Court of the Gentiles, Jesus is about to undertake a bold and outrageous moment of revolution.

For this Passover will not be like those that have come before. It will be remembered throughout history for words of anger. Unfurling his whip, Jesus prepares to launch his ministry.

* * *

The partially enclosed Temple courts reek of blood and livestock. Tables piled with coins line one wall, in the shade of the Temple awnings, lorded over by scheming men known as

shulhanim

, “money changers.” In long lines, out-of-towners await their chance to exchange their meager wealth in the form of coins minted by agents of Rome. The Roman coins are adorned with images of living things such as gods or with portraits of the emperor. But this coinage must be converted into shekels,

3

the standard currency of Jerusalem. In keeping with the Jewish law forbidding graven images, these special coins are decorated with images of plants and other nonhuman likenesses. Also known as the “Temple tax coin,” the shekel is disparaged by many pilgrims because it is the only form of money acceptable for paying the annual tax or for purchasing animals for ritual slaughter.