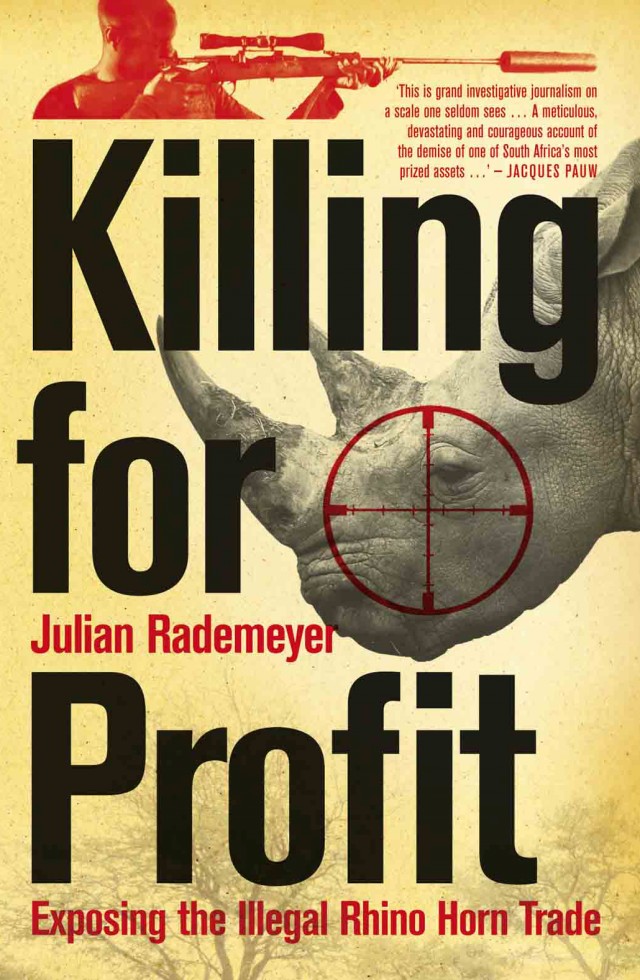

Killing for Profit: Exposing the Illegal Rhino Horn Trade

Read Killing for Profit: Exposing the Illegal Rhino Horn Trade Online

Authors: Julian Rademeyer

Tags: #A terrifying true story of greed, #corruption, #depravity and ruthless criminal enterprise…

Published by Zebra Press

an imprint of Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd Company Reg. No. 1966/003153/07

Wembley Square, First Floor, Solan Road, Gardens, Cape Town, 8001

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa

Publication © Zebra Press 2012

Text © Julian Rademeyer

Extract from ‘Run, Rhino, Run’ used with permission by Bud Cockcroft; © Bud Cockcroft

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners.

PUBLISHER

: Marlene Fryer

EDITOR

: Ronel Richter-Herbert

PROOFREADER

: Jane Housdon

TEXT DESIGNER

: Monique Oberholzer

INDEXER

: Cliff Perusset

TYPESETTER

: Catherine Coetzer

ISBN: 978 1 77022 334 9 (print)

ISBN: 978 177022 335 6 (ePub)

ISBN: 978 1 77022 336 3 (PDF)

14 Shopping for Rhino Horn in Hanoi

For Trish, without whom this book could never have been written

The Lao People’s Democratic Republic, December 2011

The sun is setting on a sweltering winter’s day in the Laotian capital, Vientiane. Across a sea of concrete lies the sickly grey Mekong River and, beyond that, a mess of cellphone towers and radio antennas. I climb the stairs of a seedy riverfront bar that reeks of stale cigarettes and alcohol, order an ice-cold quart of Beerlao Lager and find a window seat.

In the far corner, two sweaty tourists play a game of pool with a bar girl wearing impossibly tight white shorts and a fake smile. The place is starting to fill up with the late-afternoon crowd.

Nine thousand kilometres from my home in South Africa, I’m nearing the end of a journey. My flight landed a few hours ago. In my backpack is a photograph, an address and the name of a company. In a folder on my laptop are scanned pages of documents detailing illegal shipments of tons of monkeys, snakes, pangolins, ivory tusks, lion bones and rhino horns. Somewhere out there is the man I’m looking for; the kingpin of an international wildlife-trafficking syndicate. I just have to find him.

Three years ago, I could not have imagined being in that bar or writing this book or quitting my job to do so. Nor could I have imagined where this journey would take me, or the depths of the greed, folly, corruption and depravity that I would encounter.

Rhinos are unique creatures. They’re a link to a distant prehistoric past, a precious relic of our long-dead history. Ian Player will never forget his first

sighting. It was sixty years ago. He was a young game ranger of twenty-five on an anti-poaching patrol. ‘It was a misty morning,’ he recalled recently. ‘I was looking into a patch of bush when two white rhino came looming out of the mist, with steam rising from their flanks and their backs, and hundreds of stable flies hovering above them. Something within me was deeply touched by this primeval scene, and I had an intuitive flash that somehow my life would be bound up with these great prehistoric animals. There was sacredness about their presence …’

Along with a pioneering wildlife veterinarian, Dr Toni Harthoorn, Player is one of the men credited with saving the southern white rhino from extinction. In the 1960s, the few remaining southern white rhino were confined to the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Game Reserve in South Africa’s Natal province (later KwaZulu-Natal). Between 1961 and 1972, more than 1 100 rhinos were translocated from there to national parks, private reserves and zoos across Africa, Europe, the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States in what was called Operation Rhino. Today, as a result of that intervention and the involvement of commercial game farmers, the number of southern white rhinos has increased tenfold, from just 1 800 in 1968 to nearly 19 000 today. Ninety-five per cent of them are found in South Africa. It is the country’s greatest conservation success story. And one that is dangerously close to being unravelled.

While rhino population growth rates in South Africa still exceed the rate at which the animals are being poached, the ‘tipping point’ is drawing nearer. As I write this, towards the end of 2012, more than 400 rhinos have been killed for their horns this year alone, and projections suggest that as many as 550 could fall victim to poachers’ guns by the year’s end. Since 2008, without fail, a grim new poaching record has been set every year. If the number of killings continues to rise unabated, it is only a matter of time before the tipping point is reached. And, as was seen in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, the results will be devastating. The black rhino population, Africa’s other species of rhinoceros, was decimated – cut down from an estimated 100 000 in 1960 to barely 2 400 in 1995. Today their position is dire and, unlike white rhinos, which are considered ‘near threatened’, they remain on the ‘critically endangered’ list.

‘Rhino have a particularly plaintive cry,’ Player wrote, ‘which once heard is never forgotten. The screams of agony from rhino that have had their horns chopped off while still alive should reach out into the hearts of all of us.’

When I first read his words, I had no idea what he meant. Months later I heard those terrible dying cries for the first time. And they have stayed with me ever since.

Perhaps the greatest irony is that rhinos are being killed for the very things that evolved to offer them a means of defence. On the black markets of Southeast Asia, rhino horn is worth more per kilogram than gold, cocaine, platinum or heroin. It is a product that people are prepared to kill and die for. In Vietnam, it has become a party drug for the wealthy and a panacea for the very sick. And yet, it offers no real scientific benefits. Its value is artificial, founded on myth and propagated by greed.

But the prices keep rising and the syndicates and the market keep evolving. Since 2009, nearly fifty rhino horns have been stolen in brazen museum robberies, break-ins and smash-and-grabs across Europe. Many of the thefts have been linked to the Rathkeale Rovers, an Irish gang also implicated in robbery, money-laundering, drug dealing, airport heists and trading in counterfeit goods. Even the Russian mob is said to have stolen a mummified woolly rhino, excavated from a Siberian glacier, for its horns. And in the United States, antique dealers and even a rodeo cowboy have pleaded guilty to conspiring to traffic rhino horn trophies that they had bought on auctions across the country. There have been attempted armed robberies of government stockpiles in South Africa. In some instances, cash-in-transit gangs and ‘ATM bombers’ have turned to rhino poaching because of the low risk involved. Poachers have grown steadily more sophisticated. Some use helicopters and veterinary sedatives. Others have amassed arsenals of weaponry. They are adept at corrupting officialdom and subverting the very regulations meant to protect the animals. And all the while, poachers are being killed and rhinos shot on a scale not seen since the ‘Zambezi Valley war’ of the 1980s.

In South Africa, a bitter debate is raging over calls for the legalisation of the trade in rhino horn as a last-ditch effort to save the animals. In China, rhinos sold by South Africa to a Chinese pharmaceutical company are penned up in a breeding farm where they regularly have their horns harvested with a purpose-built ‘self-suction living rhinoceros horn-scraping tool’. The company, Long Hui Pharmaceutical, is reportedly pressing local government for permission to legally sell horn it has so far gathered under the auspices of ‘scientific research’.