Jungle of Snakes (24 page)

Authors: James R. Arnold

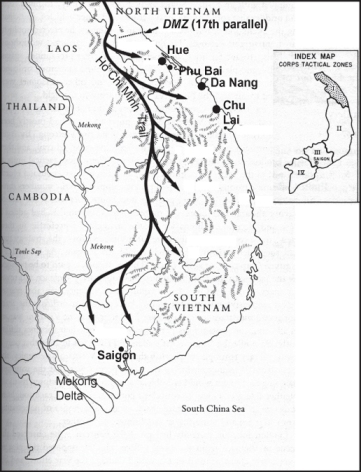

In the Phu Bai area, as elsewhere, each village consisted of multiple smaller hamlets. At first the marines visited the hamlets

only during the day and while accompanied by the militia. They avoided direct contact with the inhabitants. Instead, each

marine kept a notebook to record his observations about the people’s daily habits. By learning what was routine, the marines

learned what was extraordinary. They acquired a special sense, “an attitude you feel,” that indicated the extent of Viet Cong

control.

12

Then, having grown confident in their new environment, the marines and Popular Forces saturated the area with nocturnal patrols

and ambushes.

Contact with armed enemy was infrequent. Alarmed by the unexpected marine tactics, the Viet Cong avoided the four CAP villages.

However, it became apparent that the Communists and the villagers had arrived at a tacit agreement whereby the Viet Cong would

leave them alone as long as the villagers contributed money and rice to the NLF. But the rice harvest of 1965 was poor and

the Communists needed food, so they sent women and children to the market to purchase rice. Villagers began tipping off the

militia, thereby allowing CAP patrols to intercept the rice agents. Ek came to learn that the armed enemy “were the easy ones”

to find and eliminate; it was the unarmed rice or tax collector or the woman who showed a torch from her home to betray an

ambush site who were the more difficult foe.”

13

Ek and his superiors judged the Phu Bai experiment with Combined Action Platoons a success. With hindsight it can be seen

that several special circumstances contributed to this outcome. The first set of CAP marines were highly motivated, experienced

volunteers who were quick-thinking and socially aware. Two thirds of this first cohort volunteered to extend their tour with

the Combined Action Program rather than depart Vietnam. Backing them were some especially competent Provincial Forces and

an unusually efficient national police unit. The four trial villages lay in open rice paddies with no easy route for Viet

Cong infiltration. Lastly, the Viet Cong responded to the marine presence with a wait-and-see attitude. Later CAPs would have

none of these advantages.

Life in the Village

THE SUCCESS AT PHU BAI PERSUADED the marine leadership to expand the Combined Action Program. Officially, the program emphasized

destroying the insurgent infrastructure embedded within each village while protecting the people and government officials

from insurgent reprisal. As it formally evolved, a fourteen-man marine rifle squad plus a navy corpsman operated with a 38-man

local militia, or popular Forces (PF) platoon. Because the marine rifle squads were dispersed around different CAP villages,

young marine sergeants or corporals held in dependent command positions. Their counterparts back in Central America during

the Banana Wars, as well as British noncommissioned officers (NCOs) in Malaya, had served in the same way. While not unprecedented,

it was still a heavy responsibility. The NCOs and their men received a short primer on Vietnamese language (although the language

barrier remained the cause of frequent and sometimes fatal misunderstandings), culture, and history before being permanently

assigned to a hamlet or village where they lived twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

For the villagers, the most popular American was the navy corpsman. Hundreds attended his sick call. As one marine rifleman

recalled, “You won’t find too many Marines that’ll dispute the fact that Doc won more hearts and minds than all of us combined.”

1

Far more difficult was the challenge of forging an effective command relationship between the marine NCO and the Vietnamese

platoon leader. It was one thing to establish the principle that they shared responsibility for the well-being of their troops

and operated on the basis of mutually agreed courses of action. It was something else to adhere to this principle.

If the men meshed, it proved a good blend, with the marines instructing the PFs in basic small-unit tactics and discipline

while the Viet namese taught the marines the terrain and informed them about the local population. In the absence of harmony,

a PF platoon commander exercised his power by refusing to cooperate. Many of the problems with the militia stemmed from sources

beyond the control of the marines. The popular Forces troops sat on the bottom of the pecking order in the allied order of

battle. They were nominally volunteers recruited within their native villages to protect their own families. In reality they

served at the discretion of the Viet namese district chiefs. Sometimes they remained in their home villages but too often

they were sent elsewhere for ancillary duties such as guarding fixed installations or acting as bodyguards for well-connected

politicians. Even worse, the PFs often received assignments outside their home villages, where the inhabitants viewed them

with the deep suspicion directed at all outsiders and foreigners. At all events, until much later in the war, the PFs received

last call on weapons and equipment. The Viet Cong outgunned them and they keenly felt their inferiority. Lastly, service in

the Popular Forces did not provide draft exemption. Consequently, most able-bodied men were in the regular forces, leaving

the ranks of the militia filled with the very young, the too old, or the physically or mentally infirm. Out of such unpromising

material, marine NCOs set to work to forge motivated anti-Communist fighters.

Special Men in a Strange Place

Like the original volunteers who served with Lieutenant Ek around Phu Bai, the nineteen-and twenty-year-old marines who volunteered

for service in the initial CAP cohort were special. They had at least four months’ combat experience and personal records

free of disciplinary blemishes. They had to receive favorable endorsements from their commanding officers and had to be without

discernible racial prejudice against the Vietnamese. This last qualification eliminated many candidates, since more than half

of all marines candidly acknowledged that they did not like any Vietnamese.

For those who made the grade, CAP duty proved lonely and dangerous. The marines involved in the Combined Action Program confronted

myriad difficulties, many of them unperceived by generals and civilian theorists. The program’s success depended on establishing

cooperation and trust with the militia and the villagers. The inability to speak the language and the difficulty of understanding

an alien culture made these goals almost unattainable. Even had the CAP marines spoken Viet namese, it would have been hard

for them to penetrate the complexities of village life with their bewildering (at least to an outsider) network of inter-and

intrafamilial relationships.

Among many cultural differences leading to tension was the attitude toward personal property. Whereas the marines believed

in the sanctity of such property, the Vietnamese did not consider “borrowing” an unused object wrong, and in the marine view

they had a very elastic notion of what constituted “unused.” If a marine came in from patrol in a rainstorm and hung up his

poncho to dry, a militiaman would borrow it to begin his patrol and perhaps return it three months later when the rainy season

had ended. Nothing provoked the marines more than the frequent thefts by the militiamen, with cameras, watches, and other

personal possessions disappearing with alarming regularity. Even items vital to security disappeared: “Every morning we would

awake to find that a few more barbed wire stakes or another roll of barbed wire had walked out of the compound overnight.”

2

The marines conceived that they and the militia were “in it”—patrolling, guarding, repairing, and the welcome respite of actually

fighting—fifty-fifty. But they saw the militia as not carrying their weight. Whereas the marines were on duty round the clock,

the “lazy” militia routinely took breaks, including three-hour siestas at noontime. Worse, too often the PFs seemed unwilling

to fight. The marines sarcastically labeled their behavior “search and avoid.” They would accidentally-on-purpose cough loudly

or discharge a weapon at a purported foe, thereby compromising a carefully set ambush. The marines knew that the village’s

sons and daughters served in the Communist ranks. They understood that a militiaman might be reluctant to fire at a potential

relative. But given that they were putting their own lives on the line, the CAP marines still found it hard to tolerate such

conduct.

In the absence of cooperative militia and living amidst an indifferent civilian population, the CAP marines could accomplish

little more than any other American soldiers. One patrol leader recalled conducting more than sixty night ambush patrols and

at least as many daytime patrols and never encountering the enemy. This led to the inevitable suspicion that the militia were

in cahoots with the Viet Cong. (The marines also suspected that an unknown number of the militia were in fact either Viet

Cong agents themselves or at least had made discreet accommodations with the enemy. So when a PF guide refused to advance

any farther along a jungle trail, a marine had to consider: was it because the dangers were really too great or because the

PFs had reached an accommodation that divided territory into “ours” and “yours”? Such suspicions led to enormous frustration,

stress, and often alienation: many marines developed an attitude that while the militia would steal anything not nailed down

and do what ever necessary to avoid danger, it didn’t matter, because the marine would be leaving pretty soon. Marines with

this attitude would not give their wholehearted effort to make the CAP program work.

WHEN THE CAP marines first moved through a typical hamlet the villagers avoided contact with them. They ducked quickly into

their homes and quieted children who called out. They exuded a palpable atmosphere of fear, avoidance, and apathy. To the

villagers, the marines were just another group of armed strangers come to plague them in a conflict without end. Indeed, throughout

the war rural people seldom shared information with outsiders, whether Americans or South Viet namese. But once the CAPs proved

that they were present for the long haul, villagers overcame their fears and began using the militia or children to relay

intelligence to the marines. Some of it was not useful, along the lines of “The VC will come here sometime next month.” But

some was: “A tax collector comes to Minh’s house to night at eleven.” If the marines and the militia successfully acted on

these tips by killing or capturing a Viet Cong tax collector or recruiting agent, by ambushing a Viet Cong propaganda team,

or by repulsing a sapper attack, the flow of actionable intelligence increased.

The PFs, in turn, gained confidence and agreed to extend the range of their patrols. Meanwhile, a marine civic action noncom

worked to obtain cement to repair hamlet wells. Other marines spent small sums in the hamlets and people began to benefit

economically from their presence. As the months passed additional positive changes in village attitudes occurred and the quality

of the intelligence improved. But progress could be undone so easily. To succeed on CAP duty, individual marines had to exhibit

nearly flawless conduct. Bad behavior by one could and did reverse months of trust building. If a marine greeted a village

girl with inappropriate familiarity or a man who never should have been assigned to CAP duty exploded in a racist rage, patient

progress was lost. External factors over which the marines had no control also impeded progress: an American vehicle accidently

injuring a hamlet child, an errant artillery round destroying a home, a passing convoy of front-line soldiers throwing objects

at the hamlet’s people out of dislike for all things Vietnamese.

Moreover, although the CAP might maintain a presence in a village for three or four years, the particular Americans involved

rotated away to other duties, thereby severing personal relationships between the marines and the villagers. As a 1969 assessment

reported, “Their replacements, fresh from the States, spoke no Vietnamese . . . and, arriving in an area that seemed to hold

no threat from the enemy, they could see little reason behind the requirements for continual military efforts. As a result,

some relaxation of discipline occurred.”

3

And this was what the patient Viet Cong agent embedded somewhere in the village waited for, even if that wait went on for

months or years.

The Viet Cong Adapt

Even when the CAP marines managed to cope with all the social problems caused by the inevitable friction between a foreign

army based in the middle of deeply suspicious rural society, the adaptable enemy could nearly always cause a setback. The

village of My Phu Thuong, located only five miles from the first marine CAP village in Phu Bai, demonstrated this adaptability.

When the CAP started to make progress, the NLF leadership summoned the best half of its twenty-man standing village guerrilla

force to a special training program. These chosen ten were to spearhead a counterattack at some future time. Meanwhile, in

their absence, recruiters entered My Phu Thuong to enlist ten replacements, including two women, all of whom belonged to the

American-armed local self-defense force.

Having dealt with its manpower problems, the Communists at My Phu Thuong also adjusted their operational methods. Because

the CAP ambush teams had begun to interdict the local trails, the guerrillas extended their underground tunnel network. Because

some villagers had begun to support CAP activities, the Viet Cong intensified attacks against informers and collaborators.

A key to Communist adaptability was the possession of good intelligence. Guided by people intimately familiar with the local

terrain, a Communist recon team would conduct a careful study. Briefing and rehearsal followed, and then came the assault.

In the seemingly pacified village of Phuy Bong it came at 2:30 a.m. when all the marines and militia were caught in the patrol

base. A North Vietnamese assault force pinned them in the base while enemy soldiers swarmed through the three hamlets that

composed the village. The Communists killed four PFs and then brazenly set up a mortar next to the village market. The mortar

fired against a bridge, undoubtedly with the intent of provoking American return fire that would damage the village. Although

in this case the ploy failed, the attackers succeeded in their goal of reminding villagers that they still were vulnerable

to reprisal. Worse, the next morning the marines discovered why their efforts to defend their base had been so difficult:

wires controlling their Claymore mines—a vital component of their defensive scheme—had been cut, rendering the mines useless.

The obvious answer was “an inside job,” betrayal by one of the militia. During the subsequent investigation matters grew so

heated that a marine apparently beat a PF. And so the precarious bonds of trust dissolved and the insurgents chalked up another

small victory.

All these factors made it hard for even dedicated CAP marines to provide village security. In the absence of security Viet

Cong terrorists struck: kidnapping the sister of a particularly effective militia officer, killing the kindly old couple who

ran a beverage stand frequented by the marines, leaving a note with the message that this was the certain fate for all traitors

pinned to the breast of a mutilated civilian who had provided intelligence to the marines. And always lurking was the fear

that someday the marines would leave and the Viet Cong would resurface.

Problems Emerge

A CAP marine had a 75 percent chance of being wounded once during his tour and a 30 percent chance of being wounded a second

time. Almost 12 percent died. High casualty rates occurred because as the program expanded the enemy recognized the threat

and made CAP villages high-priority targets. They were particularly vulnerable at night, when most of the defenders were out

on patrol and only four marines and six or so popular Forces remained. Thus a typical nocturnal attack by fifty or sixty Viet

Cong enjoyed overwhelming numerical advantage and routinely inflicted serious losses. And, as had been the case with the CIDG

camps established by the Special Forces, reaction forces—this time American, not South Vietnamese—were reluctant to come to

the rescue because they feared night ambush.