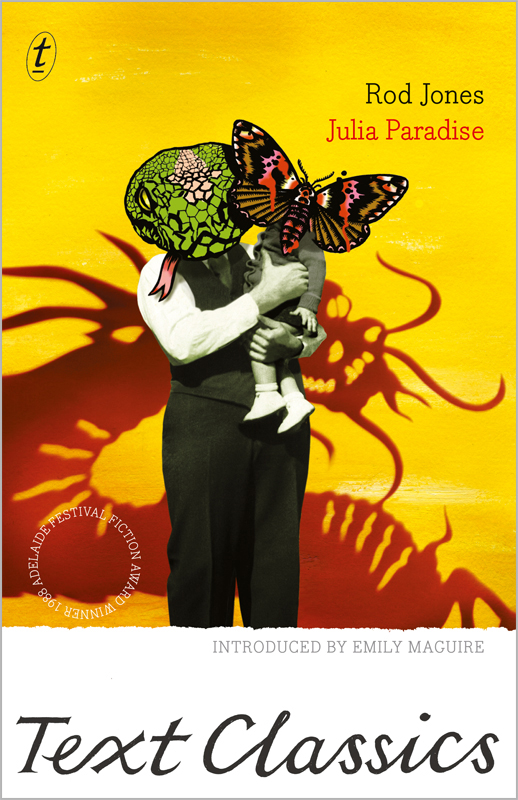

Julia Paradise

Authors: Rod Jones

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

ROD JONES

was born in 1953. He grew up in Melbourne and studied at the University of Melbourne.

Jones's first novel,

Julia Paradise

(1986), won the fiction award at the 1988 Adelaide Festival, was shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Award and was runner-up for the Prix Femina Ãtranger. It has been translated into ten languages and published throughout the world.

Prince of the Lilies

appeared in 1991 and Jones's third novel,

Billy Sunday

, four years later.

Billy Sunday

was the 1995

Age

fiction Book of the Year and won the 1996 National Book Council Award for fiction. The

Boston Globe

called it âthe Great American Novel'.

The follow-up,

Nightpictures

, was shortlisted for the 1998 Miles Franklin Award.

Swan Bay

(2003), Jones's fifth and most recent novel, was shortlisted for the New South Wales Premier's and Queensland Literary Awards.

All of his books are short and complex, avowedly literary and sometimes controversial. âWe tell stories about things we can't talk about,' Jones has said.

He has taught at various Australian institutions, including a four-year stint as a writer in residence at La Trobe University, and overseas.

Rod Jones lives near Melbourne. He is working on a novel,

Empire Street

, to be published by Text in 2014.

EMILY MAGUIRE

is the author of the novels

Fishing for Tigers

, S

moke in the Room

,

The Gospel According to Luke

and

Taming the Beast

, an international bestseller. Her non-fiction book,

Princesses and Pornstars

, was also published in a young-adult edition,

Your Skirt's Too Short

. She has written for the

Sydney Morning Herald

,

Age

,

Australian

and

Observer

.

Â

ALSO BY ROD JONES

Â

Prince of the Lilies

Billy Sunday

Nightpictures

Swan Bay

Â

Â

Â

Â

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Rod Jones 1986

Introduction copyright © Emily Maguire 2013

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by McPhee Gribble Publishers 1986

This edition published by The Text Publishing Company 2013

Cover design by WH Chong

Page design by Text

Typeset by Midland Typesetters

Printed in Australia by Griffin Press, an Accredited ISO AS/NZS 14001:2004

Environmental Management System printer

Primary print ISBN: 9781922147127

Ebook ISBN: 9781922148193

Author: Jones, Rod, 1953â

Title: Julia Paradise / by Rod Jones; introduced by Emily Maguire.

Series: Text classics.

Dewey Number: A823.3

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

CONTENTS

Â

The Cure

by Emily Maguire

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

JULIA Paradise

had no shortage of fans when it was first published. Winner of the South Australian Premier's Fiction Award, runner-up in France's Prix Femina Ãtranger, shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Award and hailed by the

New York Times

as âa remarkable accomplishment', Rod Jones's slim debut was taken up enthusiastically by readers around the world. A quarter of a century (and, for Jones, another four highly acclaimed novels) later,

Julia Paradise

will seem to first-time readers as startling as it did back in 1986. To those picking it up again it will be even better: few books reward rereading quite so richly.

Kenneth Ayres, a thirty-four-year-old Scottish doctor with some resemblance to his one-time master Sigmund Freud, spends his days psychoanalysing the âhysterical' wives and daughters of British expats, and his nights in the Chinese brothels and international clubs of decadent, cosmopolitan, seemingly lawless 1920s Shanghai. He has âno interest at all' in his adopted homeland. He arrived on a whim and stayed because it is a pleasant, easy life and because, having disappointed his military father with his career choice and been made a widower by the 1919 flu epidemic, he had no good reason to leave.

Julia Paradise, a young Australian morphine addict who hallucinates animals and fire, and recently beat her pet dog to death with a walking stick, is brought to Ayres by her husband, the Reverend Willy Paradise, a Methodist missionary. Under hypnosis she describes âwild and often obscene flights of fancy into her world of the animals', and reveals a nightmarish childhood on an isolated northern Queensland plantation:

Â

Mosses crept around the window frames, tree ferns sprouted from the outside walls, and when leaves and overhanging branches fell onto the roof they rotted there and provided a rich compost base for the next generation of parasitical growth. A small softwood tree with shiny oval-shaped leaves grew out of the veranda and the roots hung down through the holes in the rusted iron roof, where they tickled the face of anyone foolish enough to walk along that veranda in the dark. It was from one of these twisted clumps of roots one afternoon as Julia sat reading her

Golden Treasury

and listening to the groans of her father and a woman making love inside the darkened house, that a green tree snake began to unwind itself...

Â

Her tyrannical and increasingly disturbed German father, an explorer and naturalist, doesn't content himself with making love to women while Julia waits outside, though; and by thirteen, motherless, friendless and mute, âshe had come to accept the insertion of his erect penis as a natural and unremarkable bodily function.'

Ayres is convinced that he is curing Julia of her hysteria by drawing out every last detail of her visions and traumas. Perhaps, but Ayres has another reason to encourage the graphic spilling of her secrets: his taste for small, childlike (or, simply, child) prostitutes. Julia's tales of being rutted by her father really get him going. Before long Ayres and Julia are lovers.

It is extraordinary that Ayresâa glutton and an opium addict; a pimp (he procures street girls for artist friends), rapist and worseâconsiders himself qualified to analyse and instruct others. But mostly he avoids self-reflection. On one occasion, drifting into an opiate haze, he feels that âhe was on the point of making a crucial confession to himself, but that he was holding himself back from such an irrevocable step as an admission of guilt: like a murderer might feel, for instance.'

Not that he's entirely in denial about his predations. He recognises these âindulgently', comforting himself with Freud's observation that âsome perverse trait or other is seldom absent from the sexual life of normal people.' He doesn't wonder about what perverse trait may be present in the girls he rapesâor might have been present had they had been allowed to develop sexual lives of their own volition.

That a man who spends much of his time listening to âfemale problems' could remain so oblivious to the experiences, inner lives and potential agency of women is the key to solving this tightly packed puzzle of a book. Ayres, thoroughly enjoying his wanderings through Julia's kaleidoscopic dreamscapes, believes her to be âthe most suggestible patient he had ever come across in his life'. Oh, Kenneth, there really are none so blind...

It's not only Ayres who misreads Julia. Her husband tells Ayres that âone of her delusions was that she considered herself to be a “serious” photographer'âand yet there is no evidence of delusion in Julia's actions. She walks the streets of Shanghai's Chinese quarter dutifully recording the lives of the city's most oppressed and exploited inhabitants. But being doubted and dismissed is the story of her life. When she was a small child, traumatised into muteness, her father, ânever entirely convinced of the genuineness of her affliction', would sneak up behind her âdescribing all the wickedness he had in store for her'.

Â

*

Â

Despite Ayres' lack of insight, it seems that his talking cureâhis fucking-and-talking cureâworks, and Julia recovers sufficiently to vacation with a friend, the German missionary Gerthilde Platz. Shortly after this trip, Ayres is invited to visit Willy Paradise's mission to celebrate Julia's thirty-first birthday. That night the mission school burns down, Willy is arrested and Ayres learns that Julia is in far more control of herselfâand, it seems, himâthan he imagined.

While this is going on, China is erupting with communist insurgencies and nationalist crackdowns. Other forces, political rather than psychological, are on the march. Ayres sees the columns of strikers moving through Shanghai and the bodies hanging from lampposts, but they have as little to do with him as the legless beggars and starving children he passes on his way to his favourite brothel. An unpleasant scene, certainly, but irrelevant to the real stuff of Kenneth Ayres' life: sex and food and the knowledge he has prevented yet another expatriate wife from embarrassing her husband by jumping at shadows.

Nevertheless, Julia's revelations are troublingâcould she have been playing games with him? Julia is âa brilliantly coloured jigsaw puzzle dismantled and spread across the floor of his mind'. He obsesses over her words and expressions, her stories and rantings, but the puzzle is unsolvable so long as he refuses to look at the other pieces: the ones staring out from the background, from the jumped-at shadows.