Journeys on the Silk Road

Read Journeys on the Silk Road Online

Authors: Joyce Morgan

JOURNEYS

ON

THE

SILK

ROAD

JOURNEYS

ON

THE

SILK

ROAD

A desert explorer, Buddha’s secret library, and the unearthing

of the world’s oldest printed book

JOYCE

MORGAN

&

CONRADWALTERS

LYONS PRESS

Guilford, Connecticut

An imprint of Globe Pequot Press

First published 2011 in Picador by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Limited

First Lyons Press edition 2012

Copyright © Joyce Morgan and Conrad Walters 2011

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press

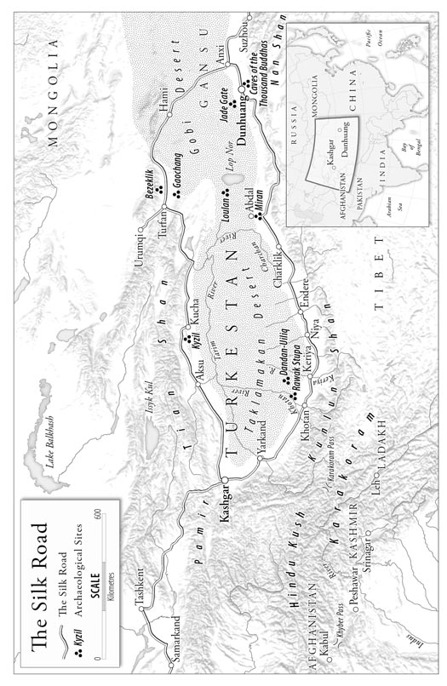

Map by Pan Macmillan

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN 978-0-7627-8297-0

Printed in the United States of America

The authors and publisher gratefully acknowledge permission to reproduce the following copyright material. While every effort has been made to trace copyright holders, we regret any inadvertent omissions.

Epigraphs from the Diamond Sutra are reprinted from

The Diamond that Cuts through Illusion: Commentaries on the Prajñaparamita Diamond Sutra

(1992) by Thich Nhat Hanh with permission of Parallax Press, Berkeley, California, www.parallax.org.

Quotations from Aurel Stein’s letters are courtesy of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

Quotations from

Ruins of Desert Cathay

and

Sand-Buried Ruins of Ancient Khotan

by Aurel Stein, and C.E.A.W. Oldham’s obituary of Aurel Stein, are courtesy of the British Academy.

Quotations from

Serindia

by Aurel Stein and

An English Lady in Chinese Turkestan

by Catherine Macartney appear by permission of Oxford University Press.

Quotations from British Museum Central Archives are courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Quotations from

Tun-huang Popular Narratives

by Victor H. Mair are courtesy of Professor Mair.

Quotations from

The Times

(London) are by permission of

The Times.

Quotation from

The Manchester Guardian

is courtesy of

The Guardian

(London).

Cartographic art by Laurie Whiddon, Map Illustrations.

E-ISBN 978-0-7627-8732-6

To our parents

Contents

13. Yesterday, Having Drunk Too Much

...

Prologue

For nearly a thousand years two attendants waited, sealed from the world in a hand-carved cave, while the sands of the great Gobi Desert crept forward. The figures, one with a topknot of black hair, the other robed in red, guarded the darkness with only a wooden staff for protection and a fan for comfort. Their cave was three paces wide by three paces deep, but they maintained a motionless vigil from the northern wall, where they merged with the room’s arid earthy browns. Outside, the winds could howl, the sun could try to bake the sand into glass and the desert could encroach with each century until even a hidden doorway to the attendants’ cave was buried. But inside, time had halted and everything was safe.

In front of the attendants were tens of thousands of manuscripts, piled as high as a man could reach. There were charts of the heavens, rules for monks, and deeds recording the ownership of slaves sold long ago. There were banners that could be unfurled from the cliffs outside and paintings on silk of enlightened beings. But outnumbering all of those were sutras—the words of the Buddha himself—piled into the black air, unheard, awaiting rebirth into a new realm.

Most were copies made with brushes dipped in lustrous charcoal ink by hands unknown, in kingdoms forgotten. But one paper sutra held special significance. It could confer spiritual blessings as no other. Where the rest were laboriously copied by long-dead scribes, this had been created with a wooden block and reproduced at a rate once unimaginable. It was the oldest printed book in the cave—the Diamond Sutra—and although no one outside knew it yet, this dated scroll was the oldest of its kind anywhere. The sutra taught that life is illusory and as fleeting as a bubble in a stream. True to its message, all who once knew the printed scroll was inside the cave had long since turned to dust, yet the Diamond Sutra itself remained intact.

Many copies of the sutra had preceded this one. Its words had been carried by man and beast through the wispy clouds of mountain passes, over the cracked earth of deserts, across the glacier-fed currents of surging rivers. In time this printed copy would cross the seas to reach lands unknown to its creators. One day it would even convey the Buddha’s wisdom invisibly through the air.

While Christians fought the Crusades and Magellan circled the globe, while Shakespeare wrote

Hamlet

and Genghis Khan united nomadic tribes, while the Black Death consumed Europe and Galileo imagined the cosmos, while Joan of Arc answered the voices in her head and Michelangelo sculpted

David,

the two attendants stood in meditative silence. Then, at the cusp of a new century, sound returned to the Library Cave. It was 1900—the Year of the Rat—and a faint noise announced the painstaking sweeping of the sand outside the attendants’ cave. Day by day, week by week, month by month, the level of the sand receded and the indistinct voices of laborers grew louder until their scrapings could be heard against the hidden door. For every moment across a millennium, the eyes of the two attendants had been open in anticipation. And, at last, a seam of light arrived.

1

The Great Race

An unforgiving wind blew clouds of dust and sand as if every grain were aimed at one tired man astride a weary pony. He urged his mount forward, determined to keep a promise. He had set out long before dawn, leaving behind his team of men and pack animals, knowing he would have to cover in one day ground that would typically take three. Traveling through the heat and glare of the Central Asian desert, he now looked on his vow—to arrive that day on the doorstep of friends in a distant oasis—as uncharacteristically rash. But for seventeen hours he pressed on across parched wastes of gravel and hard-baked earth.

As dusk approached, the sting of the day’s heat eased, yet the failing light compounded his struggle to keep to the track amid the blinding sand. His destination of Kashgar could not be far away. But where? He was lost. He looked for someone—anyone—who could offer directions, but the locals knew better than to go into the desert at night during a howling wind storm. He found a farm worker in a dilapidated shack and appealed for help to set him back on the path. But the man had no desire to step outside and guide a dirt-caked foreigner back to the road, until enticed by a piece of silver.

The rider still had seven miles to go. He groped his way forward as the horse stumbled in ankle-deep dust. Eventually, he collided with a tree and felt his way along a familiar avenue until he reached the outskirts of the old town. Then, as if conceding defeat, the wind abated and lights could be glimpsed through the murky dark. He crossed a creaking wooden bridge to reach the mud walls that encircled the oasis. The guns that signaled the sunset closing of the iron gates to the old Muslim oasis had been fired hours ago. The only sound was the howling of dogs, alert to the clip-clopping of a stranger on horseback passing outside the high wall. He continued until he reached a laneway. He had covered more than sixty miles to reach Chini Bagh, the home of good friends and an unlikely outpost of British sensibilities on the edge of the Taklamakan Desert. Its gates were open in anticipation. He shouted to announce his arrival. For a moment, silence. Then surprised voices erupted in the darkness as servants recognized him. At last Aurel Stein had arrived. They moved closer to greet the man they had not seen for five years. At forty-three, he was no longer young, but his features were as angular as ever, and his body—though just five feet four inches tall—still deceptively strong.