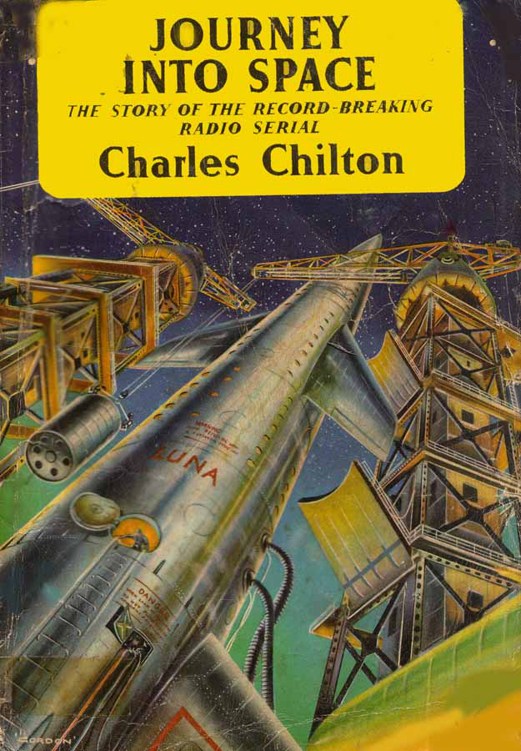

Journey Into Space

First published 1954

From the first BBC radio series ‘

Journey to the Moon’ (Operation Luna)

All the characters in this book are entirely fictitious and have no relation whatsoever to any living person.

Front left, Andrew Faulds as Jet; front right, Don Sharp as Mitch; back left, Alfie Bass as Lemmy; back right, Guy Kingsley Poynter as Doc.

November 20th, 1965.

The first shock came just after we had completed the circuit round the Moon. We were almost at the point where it was necessary to cut in the motors for a short burst, just powerful enough to take us out of the free orbit round the Earth’s satellite and set us on course for home.

On Jet Morgan’s orders, we had taken up our places on the take-off couches. The little televiewer poised less than two feet above my face showed a sharp picture of the pitted surface of the Moon’s southern hemisphere as it slowly unrolled beneath us. Little more than half-way up the screen, sharply defined against the black lunar sky, was the curved horizon. Any moment now, like a rising sun, the Earth would appear above it.

“There she is.” It was Mitch, our engineer, who saw her first.

“You sound as though you haven’t seen her in years,” said Jet.

“I feel like I haven’t.”

Jet didn’t pursue the conversation any further. “Position, Lemmy?”

“Coming into centre, five degrees.”

“Stabiliser, Doc.”

“Stabiliser,” I repeated and pressed the button. The low hum of the big gyro filled the ship and gradually the Earth moved into the centre of the televiewer screen.

“Stand by to switch in motor.”

“OK,” said Mitch. “I--hey, wait a minute!”

“Huh? What’s the matter?”

“The fuel--there’s hardly any left.”

“What?” The shock we all felt was clearly reflected in Jet’s voice. “But you told me there was plenty--oodles of it, you said.”

“Well, there’s not now. Something’s gone wrong. We’ve lost it somewhere.”

“Three degrees,” said Lemmy, apparently unconcerned.

Jet ignored him. “Then we must have used up much more than you estimated,” he said to Mitch.

“But we couldn’t have done, not on a Moon take-off. We shouldn’t have used half of it.”

“Two degrees.”

“Have we got enough to set us on course for Earth?”

“Just about but no more.”

“Then stand by to fire the motor.”

“Standing by,” said Mitch.

“One degree.”

“Contact!”

The ship shook as the powerful motor sprang to life. Speed began to increase and with it the gravitational pressure. I looked up at the televiewer to see how we were doing. The Earth had drifted slightly out of centre but was now coming back into it again. By the time we had reached maximum speed we were pointing straight towards the globe, and the Moon’s surface was no longer visible.

“Cut the motor,” ordered Jet.

The ship ceased to tremble. Gravity-less conditions returned and Lemmy heaved an audible sigh of relief. “Course correct,” he said.

“Cut the stabiliser, Doc.”

I cut it, and once more, but for the pulsating of the televiewer and the hum of the power packs, silence fell upon our tight little cabin.

“Lemmy, call up base and let me know the moment you get them.”

“Right.” Lemmy pressed a switch above his bunk and his control panel slid back into its stowage position in the wall, automatically disconnecting itself from the main circuit as it did so. He unfastened his safety straps and half climbed, half floated down the ladder which led from his bunk to the floor, his magnetic boots making metallic clicks as he descended. I had already unfastened my straps and was putting on my boots when Jet’s next order was given.

“Better check with those fuel gauges, Mitch. Make sure the fault isn’t with them.”

“Too right I will.” Mitch made his way towards the engineering control panel.

Now Lemmy’s voice could be heard calling Earth. “Hullo, Luna calling. Calling Control. Come in please.”

The loudspeaker spluttered and hissed. Two seconds later the voice of Control came up from Earth.

“Hullo, Luna. Luna City calling. Standing by.”

“I’ve got ‘em, Jet,” called Lemmy, but it was hardly necessary; Jet was already at his elbow.

“Morgan here. We’ve completed our circuit, have taken numerous photographs and are now heading back to Earth. We expect to be within landing distance in four and a half days from now.”

“Thank you, Luna. What did the other side of the Moon look like?”

“Much the same as this side, except that there’s a crater there--a large crater. Much bigger than you can see from Earth. It’s colossal.”

“Is that all?” There was a note of humour in Control’s voice. “No green-eyed monsters or anything?”

Jet laughed. “No, no green-eyed monsters. Look, we have to make our routine checks now and we’ll all be pretty busy for a bit. We’ll call you again in two hours.”

“Right. And while you’re coasting home you’d better get all the rest you can.”

“Huh? What for?”

“Because you’re certainly going to get a big reception when you get here. I think every Prime Minister in the Commonwealth intends flying out to greet you when you land.”

“Blimey!” The interjection came from Lemmy. He switched off the radio and the tape recorder which served as the log.

By now Mitch had returned from the engineering control panel. He looked worried. “I can’t understand it, Jet,” he said. “The gauges are right, the fuel tanks

are

empty. Well, as empty as makes no difference.”

“But they can’t be. We carried enough reserve for an emergency landing and we haven’t used any of that.”

“They’re dry just the same. What little we have left is

in

the reserve tanks.”

“Impossible. The motor could never burn up fuel at that rate, it would wreck the ship.”

Jet was right, of course. But then where had it gone? Less than two hours ago, when the pre-take-off checks were made, the fuel had been there; enough for all our normal needs and some to spare. Now there was virtually none. Should an emergency arise, should we drift off course, or overshoot the landing base, there was nothing we could do about it. These were the thoughts that were flashing through my mind when I made a discovery as startling as that just made by Mitch.

Periodically it was my duty to check and adjust the oxygen supply. I needed no reminder from Jet to carry out this operation. The moment our course for Earth had been set, I had gone over to the air-conditioning panel to carry out my routine. There I found, as Mitch had, that supplies were far less than they should have been. I checked again to make sure. There was no doubt about it. Since taking off from the Moon, one-tenth of our oxygen supply had been used up.

I hurried across to Jet to report the news. He ran his fingers through his unruly, black hair and looked at me as though I were crazy. “What is going on?” he exclaimed. “We couldn’t have used up half a day’s supply in less than two hours.”

“Well, we have,” I told him.

Jet was perplexed which wasn’t surprising. First the fuel, now the oxygen. The whole thing was fantastic. Impossible. But Mitch’s gauges and my indicators did not lie.

After a moment’s thought, Jet decided we should search the ship. As he said: “If hundreds of gallons of fuel and half a day’s supply of oxygen can disappear in this way, other things can disappear, too.” We divided the ship into four parts and every one of us began a thorough check of the portion allotted to him.

First we calculated the exact loss of fuel and oxygen. Half an hour later we checked again but found the fuel gauges had remained static and the oxygen was down by only the normal amount needed to replenish the air. All other parts of the ship, batteries, radar, radio and televiewer circuits appeared normal, and in good working order.

At Jet’s request, I figured out exactly how long our oxygen supply would last, assuming no further ‘evaporation’ took place. There was enough for 110 hours, two hours longer than the time required for us to coast back to Earth and make the difficult glide-landing through its atmosphere. We might make it, provided nothing happened to delay us and that we could land without the aid of the motor which, now that there was insufficient fuel to fire it, was useless anyway.

Our plight was serious; our chances of landing back on Earth safely were slim. We had just about got used to this idea when we received the biggest shock of all. It came when we examined the food supplies. Luna carried no cook, nor any means - whereby food could be heated, for the overall weight of the space craft had had to be kept to the minimum. Liquid, principally cold tea and fruit juice, was drunk from bottles with the aid of straws; solid food was kept in airtight containers and was of the ‘snack’ variety; bread, cooked meats, cheeses, canned fruit and vegetables. As with the oxygen, we had had sufficient food for thirty-eight days. Thirty-three of those days had already been spent out in space; fourteen days longer than had been intended. Even so there should have been food and drink for another five. There was. There was, in fact, considerably more, but what, as Lemmy described it, ‘shook us to the roots’, was the fact that the food had completely changed. Instead of tea or fruit juice, the bottles contained only water. And in the solid food containers was a pale yellow, sticky, spongy substance that none of us could recollect ever having seen before. We stared at the stuff incredulously, unable to believe our eyes.

“What on earth has happened to it?” It was Jet speaking. “It seems to have undergone a complete chemical change.”

“You once told me,” said Lemmy rather bitterly, “that when we reached outer space we would make new and startling discoveries. Well, we have. Fuel evaporates and food turns to something else.”

As ship’s doctor, the food supplies were my responsibility. Our diet had been carefully planned and the containers, both for the fluids and solids, were of my design. Within them, our precious rations should have kept fresh and wholesome throughout the voyage, even if it had taken longer than we had anticipated--which it had. I could in no way account for this metamorphosis. But, as Lemmy pointed out in his simple but logical way, the important question was not how the food had changed but, since it had, whether it was still good to eat.

There was only one way to find out. I broke off a piece of the strange substance. It was soft and a little sticky, like a newly baked, rich cake. I examined it a moment then placed it, rather gingerly, in my mouth. Taking courage, I crushed it between my teeth and rolled it with my tongue.

“Well, what’s it like?” said Mitch. His sun-tanned, leathery face was grim.

“Not bad,” I told him. “Rather sweet, like honey, but with the texture of bread. I don’t think this will do us any harm.”

“It had better not,” said Jet. “It’s all we’ve got to live on for the next five days.”

“And how about the water?” asked Lemmy.

I took a suck at the straw, held the liquid in my mouth for a few seconds and then swallowed it.

“Clean and fresh,” I pronounced. “We’ll neither starve nor die of thirst.”

“What if there’s any delayed action?”

“I don’t think there will be, but don’t anybody else touch it. If I’m not writhing on the floor within the next three hours we can count it as safe.”

“That was a stupid thing to have done, Doc,” said Jet. “Supposing it had been poisonous?”

“How else could I have tested it? There’s no laboratory aboard this ship and no dog to try the stuff on.”

Jet left it at that. He stood in silence while the rest of us waited for him to announce the next move. “The whole thing beats me,” he said at last. “Any of you got any ideas?”

We hadn’t. We were all as baffled as he was.

“Well, it couldn’t happen for no reason at all, could it?” said Lemmy.

Then Jet thought of my diary. The ship’s official log was tape recorded, of course, but, for my own amusement, I had kept a personal diary since before we left Earth. I had continued to keep it throughout the trip and found it a pleasant and satisfying method of passing away the idle hours while we were coasting through space. It also served as a complete record of every man’s reaction, including my own, to every circumstance we had met up to now. And we had been in some very strange circumstances, one way and another, which is why we were now heading back to Earth fourteen days behind schedule. There had been one period when the tape recorder had been out of action for two weeks. During that time my diary became the ship’s official log and all that happened to us was recorded by hand as concisely and faithfully as possible.