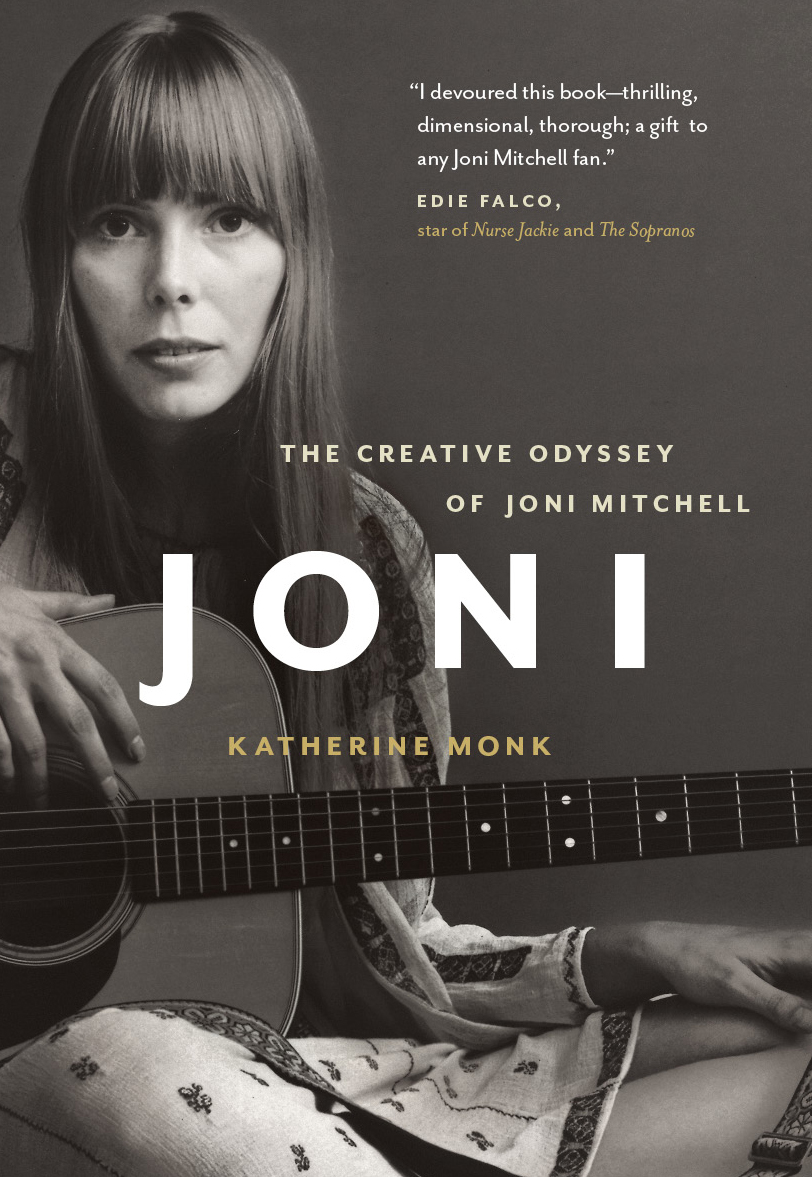

Joni: The Creative Odyssey of Joni Mitchell

Read Joni: The Creative Odyssey of Joni Mitchell Online

Authors: Katherine Monk

“Alas, who knows what in himself prevails. Mildness? Terror? Glances, voices, books?”

âRainer Maria Rilke,

Späte Gedichte (Later Poems)

For my mother, Joan: healer, hugger, creator

I will be honest. I wasn't a huge Joni Mitchell fan before all this started. Sure, I think

Blue

is probably one of the ten best records ever made, and Mitchell deserves every accolade she's receivedâas well as all the ones she hasn't. But like so many people who grew up listening to Mitchell's vast catalogue in large part by sonic osmosis, I had a preformed idea about who she was and what her songs were about. To me, the name “Joni” conjured thoughts of earnest heartbreak, wholesome hippie-ness, mournful love songs delivered in high soprano, and, well, macramé plant hangers. These loose impressions were attached to the lattice of her legend, which I learned of as a kid growing up in Canada during the seventies.

My first memories of Mitchell's music go back to early childhood, sitting in my older sister's bedroom: Tracy had the record player, a fancy model that functioned like a primitive jukebox. My mother had given her Joni's 1968 debut,

Song to a Seagull

, wrapped alongside

The Best of Peter, Paul and Mary: Ten Years Together

. Half the fun was watching the records drop with an achingly slow mechanical clicking sound. The rest of the joy was suckled from the tinny tweeter as the milk of seventies rock poured from the grey plastic casing, quivering with each thump of electric bass. When we heard “Night in the City,” Mitchell's upbeat single off

Seagull

, we'd giggle until our tummies hurt. Something about the yodelling octave shifts made us giddy, and of course we tried to sing alongâif you could call the noises we made “singing.”

The rest of the album made my stomach hurt for other reasons. Most of the music sounded so mournful and lonely, it sent a prematurely existential shiver down my six-year-old spine. It certainly wasn't

Sesame Street

. I loved

Sesame Street

, and if there was any real pole star in my early life, it was Ernie, the oddly ageless, somewhat genderless Muppet in a striped jersey. I loved the way Ernie laughed.

After researching this book, I believe Mitchell probably would have dug Ernie, tooâbecause, in some ways, she's an ageless, genderless Muppet with a penchant for mischief. That's certainly one of the sides I've come to know as a result of my Joni voyage, but for most members of Mitchell's generation, the very name “Joni” is spoken with reverenceâalongside “Jimi,” “Leonard,” and “Dylan.”

My mother's record collection featured all these names on skinny album spines. It was contained in a cupboard above the stereo with wooden sides, and it did not mingle with the second-hand rock albums my sister and I had lying about the floor or stacked six-deep on her plastic party machine. My mother had Beethoven and Bach, as well as Barbra, Janis, and Nana, but most of the records in her collection were bought for the cover art. She would use the large colourful graphic squares to gussy up her showroom at work, where she tried her best to display silky hectares of fashion scarves without the aid of models, lighting, display equipment, or great amounts of space. She made do with a few Styrofoam heads in berets and, of course, scarves. These Pucci-esque silks and rectilinear polyesters were displayed before a wall of record covers. This added a sense of urbane chic to the otherwise rundown shmatte palace in Chabanel, the needle trade ghetto on the north side of Montreal. When the displays finally came down, the records came home. My mother gave them a chance. She would listen. Sometimes she would dance. She has little recollection of this. Not because she's senile or dead. But because the musical part of her being seems to be something she sees as part of her pastâa part of her life she left behind, in the basement, above the now-broken stereo that won't turn off unless you unplug it.

It's when I think about my mother that I feel an urgent sense of purpose behind this book. My mother is, and always was, a highly intelligent and creative woman. Yet most of her artistic energy has been spent on cooking, flower arranging for the church, sewing terry cloth onesies for me and my sister, and pursuing her many business venturesâwhich led to that novel commingling of gatefold record sleeves and scarves. She had no time to be creative, she would sayâlike we all say, because we, as a society, undervalue the creative impulse. We almost mock the idea of being “an artist for a living.” But as I've come to discover, being an artist is living. Joni Mitchell taught me that.

It was the first of many lessons writing this book taught me, but it was probably the most transformative: it framed the rest of the journey and brought new meaning to the project itself. The closer I came via Joni Mitchell's life to the core of the creative experience, the closer I came to understanding my own creative potentialâand the underlying pulse of this book. This is very much a book about Joni Mitchell but, at its heart, it attempts to celebrate the essence of the creative experience. In the end, that's what Mitchell's life odyssey was all about: attaining meaning via the act of making something.

This lifelong drive is unfathomably simple and universally applicable but surprisingly easy to misunderstand, especially when you add thick layers of philosophy, calcified deposits of bad press, and a standoffish relationship with the public.

I soon learned that I'd had a completely inaccurate view of who Joni Mitchell really wasâeven if I knew the basic outlines of her biography. For instance, I knew that she was raised in Saskatchewan, dated James Taylor, lived in Laurel Canyon, wrote “Both Sides Now,” released the universally beloved

Blue

, and won several Grammys. I also knew she chain-smoked sans apology, had a baby no one knew about, surrendered her for adoption, and reunited with her more than thirty years later in an estrogen-fuelled media circus of attention and awkward, forced intimacy.

Perhaps the most daunting fact of all was Mitchell's noted distaste for the media. As a reporter who once covered pop music, I knew some of her “people.” I was aware that Mitchell never liked doing interviews and retired from show business on several occasions because it was too exhausting to be continually misunderstood in the scum pond of celebrity sound bites. In fact, at the dawn of this project, Mitchell was already done with biographers. As one of her last remaining business representatives told me: “She doesn't even want me sending solicitations. Nothing. She will not talk to you.”

A huge problem quickly reared its head: How do I add anything original to the already exhaustive amount of Joni material without any new Joni Mitchell musings? The answer was not immediately apparent, but after immersing myself in the Joni Mitchell archive for a few months in the hope of finding a great big hole to fill with a new book, the outlines of a very different Mitchell began to emerge. And she was nothing like the person I thought she was.

She was a lot more complex, more literate, and far more creativeâas an entire human being and not just as an artistâthan I had ever imagined. She was full of fabulous paradoxes, damning and redeeming herself in the same breath. One minute she would be trashing the status quo with righteous zeal, and the very next, she'd recoil at the idea she sounded badass. Similarly, she hated doing interviews, yet some of the transcriptions are fifty thousand words long. There was an almost amorphous quality to the person emerging between the lines of text and archived interviews. She was not the mono-dimensional Joni monolith I was expecting. She was an evolving force of nature and, most importantly, an ever-questioning creative spirit.

I soon discovered Mitchell's inquisitiveness wasn't limited to the arts. As I pored over interviews, I realized she had a profound interest in philosophy and religion that guided her oeuvre. But she was also self-taught and, therefore, largely unencumbered by the academic posturing that can halt honest learning in its tracks. She pulled ideas together in a novel and entirely personal way. Romanticism, asceticism, nihilism, and humanism seemed to bleed from the same sliced vein of expression without the cauterizing influence of a formally educated intellect. As a result, Joni Mitchell could dance down original paths of enlightenment, going boldly where few musicians could ever hope to go.

She'd traipsed across the hostile landscapes of modern thought, where the likes of Martin Heidegger, Albert Camus, and Friedrich Nietzsche forever ride the metaphysical merry-go-round, chasing the elusive ring of human meaning. Mitchell frequently cited these sources, and many more, to the music journos who poked and probed at her artistic soul. She wasn't always quoting them verbatim, and she often mixed chunks of ideas together, but there was no doubt she grasped the material, internalized it, and expressed it in her words and music. Despite some snide insinuations, she wasn't reading the deep stuff to show off, or to prove herself literate to the frequently phony entertainment community. She was reading to understand herself, and her work. As a result, these big ideas would become compass points on her creative journey, with none other than Nietzscheâthe granddaddy of nihilism and the man who killed Godâemerging as the central

N

, her true north, on the map of her life.

Just how much Nietzsche influenced Joni Mitchell's oeuvre was probably the biggest surprise of all. While many writers had noted Mitchell's affection for Nietzsche's most literary work,

Thus Spoke Zarathustra:

A Book For Everyone and No One

, usually that analysis went no further than a nod to a handful of songs that Mitchell herself described as Nietz-schean. The biographical gap I was seeking stood before my feet, and within hours of rereading

Zarathustra

, I was sucked into what I can only describe as a Nietzschean wormhole where the macramé plant hangers, gingham dresses, and patchouli that once framed my impressions of Joni Mitchell vaporized in a thundercloud of creative power. It did not take me long to realize that this woman had gone far beyond the boundaries of the standard singer-songwriter. She was more of an artist-astronaut, extracting the ore of human meaning from the act of personal creation.

By the time I finished the research, I felt Joni Mitchell might be the only artist on the planet to survive the music industry with her soul intact. Hell, she may be the only human being in modern existence to approach the creative heights of the Nietzschean Supermanâan individual who reconciles all his petty human flaws to become a true creator, or what Nietzsche described as “the lightning from the dark cloud of man.”

1

I know that sounds a little inflated and maybe downright pedantic. But that's the rock I landed on. After walking through the door as an ambivalent observer, with absolutely no ego stake in the narrative or any messianic image to protect, I found myself feeling profound admiration for Mitchell and her unmatched courage in a world where art meets commerce in a head-on collision.

She has created one of the most enduring catalogues in the history of popular music, but she isn't like any other pop musician, folk legend, or celebrity icon I have ever encountered. Her work, her life, and her world view form a unique tapestry in the annals of popular culture because they have complete integrity. She never dropped a stitch of self. There are no holes of compromise, or any moth-eaten patches of pandering commercialism. Due to a confluence of benevolent circumstances, Mitchell was able to call her own shots from the beginning of her career: her first recording deal with Reprise Records gave her full creative control over every album, from internal content to external packaging. I can't overstate how rare, and how important, this piece of Mitchell biography is: it means she was in control of the artifacts from day one. It also means we can look at her career as a pure example of the pop star phenomenon, untainted by the usual peer and commercial pressures. Where most performers are essentially chauffeured around their own lives, driven by trends and an agent's profiteering advice, Mitchell has always piloted her own craft. She did not “show her tits” or “grab her crotch,” nor did she suffer through any outsider's attempt to turn her work into focus-grouped sludge. She held true to her fluctuating and often fickle creative muses and managed to emerge as an icon recognized the world over.

Where did Joni Mitchell gain her creative strength and vision? And in this age of just-add-water pop stars on

American Idol

, what does it mean to be a creator anyway? Do we need artists, or have the suits successfully sold us on the deep meaning of money and all the other abstracts our society assigns as “valuable”?

These are not new questions. Fortunately, the greatest thinkers in history applied themselves to these problems. Better still, Joni Mitchell read their work and transmitted their messages through song.

All I had to do was tease out the tangle. In order to do so, I had to dive into the deep end of a pool I normally waded in. I read a lot of philosophy and psychoanalytic theory. From Martin Heidegger to Rilke, Joseph Campbell to Sigmund Freud, Ellen Levine to Nietzsche, I immersed myself in ancient and contemporary thoughts about the creative process in the hope of decrypting Joni Mitchell's artistic success.

I have endeavoured to integrate these ideas into the text and to show how each golden philosophical thread helped Mitchell through the labyrinth of the artistic process. After all, the creative life offers up a never-ending series of challenges that must be overcome, and Mitchell found strength and purpose at each turn, partly because of her stubborn personality, but also because she had a philosophical grounding that gave her perspective. So there are many skeins of philosophical fleece twisting through this odyssey, but each one leads to the same whole Joni.

From Joseph Campbell, we can glean the importance of myth and mythmaking to the human experience. Campbell believed we crave mythical stories to help us unravel our own mysterious sense of meaning and feel the magic of existence. From Freud and his former student Carl Jungânot to mention Abraham Maslow, Ellen Levine, and all the other psych-types who see the creative act as the most important difference between us and our primate cousinsâwe can learn to use the language of psychology to describe the creative impulse and its role in personal realization. These thinkers believe that creative activity is a psychic cure for existential angst because it attaches us to the creative power of the universe itself and gives us a sense of belonging to something larger than ourselves.