John Saturnall's Feast (37 page)

Read John Saturnall's Feast Online

Authors: Lawrence Norfolk

They began to walk.

‘That fever burned hotter than fire,’ Abel said. ‘And the hotter I burned the higher I flew. Half of me was in that cot. The other half was up with the angels. Except there weren't no angels, John. There weren't nothing up there. When I came down again, you and your ma were gone. Cassie told me you'd run up into Buccla's Wood. Marpot took us off to find Eden. Marched us out on the Levels all the way to Zoyland. But it weren't no Eden . . .’

The moon rose higher. John's face felt wet. He wiped his forehead with his sleeve but the sensation persisted. The bleeding from his head, he supposed. He stumbled beside Abel who stared over the pasture, grey-faced in the bleaching light.

‘Weren't even a church,’ Abel resumed as John remembered the picture in Calybute's news-sheet. ‘Just a barn. Marpot put the women in there and had ’em strip naked.’

‘Not Cassie,’ John said.

Abel grinned. ‘You were sweet on her, weren't you?’

‘Yes,’ John said. It did not seem to matter what he admitted to Abel. ‘I was. I thought she was sweet on me too.’

‘Think of it,’ Abel went on. ‘Our Cass married to a cook at the Manor. Be better'n what she got.’

‘How did you know I was a cook?’ John asked.

‘You ain't no soldier, are you?’

They tramped along the edges of moonlit fields, John unsure if they were prisoner and captor or two fugitives united in flight. For long minutes Abel would seem to forget John's presence. But whenever John was about to break the silence, Abel would speak again.

‘Marpot hauled that priest out at Buckland,’ he said abruptly.

‘You were there?’

‘Saw as much as I needed. If you lend the Devil a finger you owe God a hand. That's Marpot's way. He carries a block on the back of a cart. He would have had your Father Yapp if it weren't for Lady Lucy. She kicked up a right fuss. You can imagine.’

John grinned. He could.

From time to time, John heard faint cries. A noise like wheels creaking came and went. They rounded a copse of trees then climbed a stile and walked across a field.

‘Abel, where are we going?’

‘Look over there.’

In the corner stood the broken-down well. John stared, his head throbbing. They must have walked in a circle, he supposed. How long could this night last?

‘Reckon you can hit it from here?’ asked Abel, rattling his bag of stones. ‘Keep your elbow high, remember? Give your wrist a flick at the end. Like this.’

He launched a pebble that flew fiat and straight to crack against the well. Then John chose a pebble, the stone feeling oddly light. He threw and the well seemed to draw the stone to it.

‘There you go,’ said Abel encouragingly. ‘That's it, John.’

John's head had begun to throb again but he no longer cared as Abel held his arm at the required angle. They were back in Buckland. It was just like the old days. But no children were sick. No torches surrounded their hut. No flames lit up the night. Abel took off his hat and jammed it on John's head.

‘You're going to be all right, John,’ Abel said. ‘Like in Buccla's Wood when your ma wouldn't wake up. Or the Manor when Sir William came down those stairs. Same here.’

John's head was pounding now. How could Abel know what happened in Buccla's Wood? Or the kitchen? He tried to frame the question but his fatigue rose in a black wave. He closed his eyes and found he could not open them again. It was too late to ask Abel now. Too late to ask anything. He was sinking deeper. Falling again. Then he felt himself land.

The ground was hard as a board, lurching and jolting against his back. A terrible stench filled his nostrils. The wet winding-sheet smell wrapped itself about him. His eyes opened.

A single eye stared into his own, dangling from a head slashed ear to jaw. Other corpses pressed down on his limbs. He was trapped beneath a jumble of arms, legs and heads, all mangled, cut, slashed or pierced. They were loaded together on a cart. The cart stopped and John began to struggle. He looked up through a gap in the limbs. A face swung into view.

‘This one's alive.’

“. . .

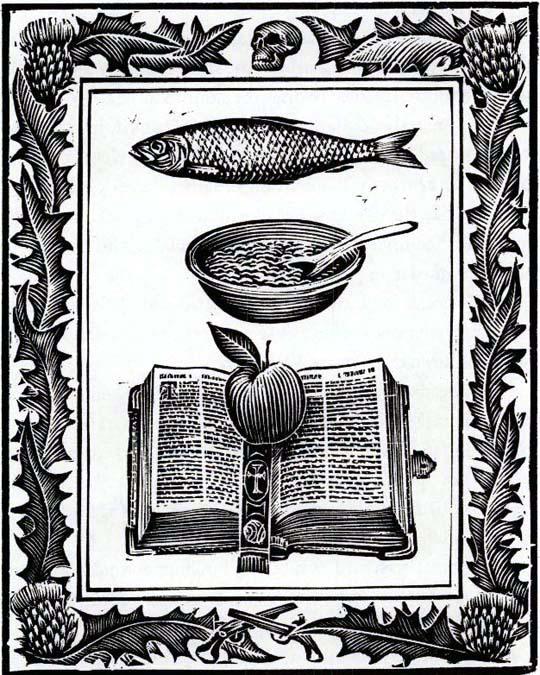

remember in

these Dishes those Times when a pickled Fish and a Bowl of Gruel was a Benison for a Lord . . .”

From

The Book of john Saturnall:

A

Feast

to commemorate the

Accession

of our late Lord High Protector, Oliver Cromwell, Gentleman

f those Multitudes who marched in the late Wars, the most Part were divided upon Naseby Field. For there did many fall, blown apart by Cannon or cut in twain by Swords, never to rise again except as Phantoms to guide the Living or as old Souls when the four Trumpets blow. Some were carried off in Tumbrels or Carts. Others limped or were borne away by their Comrades. Some rode from the blood-stained Sward upon a stolen Horse. Others marched as Victors.

f those Multitudes who marched in the late Wars, the most Part were divided upon Naseby Field. For there did many fall, blown apart by Cannon or cut in twain by Swords, never to rise again except as Phantoms to guide the Living or as old Souls when the four Trumpets blow. Some were carried off in Tumbrels or Carts. Others limped or were borne away by their Comrades. Some rode from the blood-stained Sward upon a stolen Horse. Others marched as Victors.

But among all these One did rise higher than all the Rest, being our first Minister as it came to pass, who was christened plain Oliver Cromwell.

Armed with Flintlock and Bible, he did preach an unfamiliar Lesson to the Nation. That there was no Christmas, nor May-feast, nor Hocktide, nor Feast or Fast. Indeed he eschewed all such Luxuries. Then Oysters were mixed with Crumbs and Dukes did seek their Dinners in the Hedgerows or they fled to the Garrets of Paris.

Find here, therefore, a Feast for that One who would have None, calling it a Papist Invention, and remember in these Dishes those Times when a pickled Fish and a Bowl of Gruel was a Benison for a Lord and a Drop-apple was Supper enough for the fattest Bishop . . .

A

GUST OF WIND BLEW

up the slope, rustling the dark crowns of the trees. Standing watch on the gatehouse, Simeon Parfitt heard the charred stubs of the gates creak as they shifted in the breeze. The red-eyed youth yawned and glanced across at the opposite turret where He-sekey's thin body was silhouetted against the pre-dawn sky.

Another two hours to breakfast, thought Simeon shuffling his feet on the planks and shivering in the pre-dawn chill. His stomach grumbled in expectation of the bowl of thin porridge.

Lady Lucretia had insisted that the gatehouse stay manned. ‘Lest our enemies mistake the Manor for one of their churches and sing their psalms on the lawn,’ as she had put it. But when the Militia had arrived, Buckland's sentries had offered scant resistance.

Simeon remembered the black-cloaked ruffians running through the corridors, smashing glass and daubing crosses, hauling armfuls of papers from Mister Pouncey's rooms before dragging the steward outside. The hangings they could not hide had fed a bonfire whose black scar still marked the lawn. Then their women had tumbled the stained wooden block from its cart and their colonel had hauled Yapp from the chapel.

That scene glowed hotly in Simeon's thoughts. A manacle had been nailed into the bloodstained wood. Yapp had soiled himself as they clamped his hand in the metal, the dark stain spreading out from his crotch. Their colonel had denounced him, his blue eyes wild. The axe had risen. Then Lady Lucretia had forced her way to the front . . .

A sharp crack resounded out of the trees, rousing Simeon from his thoughts. Little enough traffic arrived at Buckland Manor by day, let alone before dawn. A fox, Simeon decided. Or a badger. He wrapped his thin cloak more tightly about him. But then, at the bottom of the hill, a figure stepped out from the trees.

On the east turret, Hesekey leaned out to stare.

‘See that?’ he hissed.

‘I do,’ Simeon replied with more assurance than he felt.

A lean man clad in a long coat stood in the road, a slouch hat pulled down over his face. As the youths watched, he began to walk up the track. With a nod to Hesekey, Simeon climbed down. They stood together beneath the smoke-blackened archway.

‘What's he want?’ whispered Hesekey.

‘How should I know?’ Simeon whispered back.

In the weeks after Naseby, bands of ragged soldiers had crept home along the drovers’ tracks. But the last of those had passed by months ago. A few beggars still came in hope of the dole-boxes in the yard. But the dole-boxes had been empty since the first winter. Perhaps a fugitive from the Militia, wondered Simeon. But the dark figure walked with an air of greater purpose.

‘He has no sword,’ Hesekey offered hopefully. ‘Can you see a sword?’ Simeon shook his head then looked back at the darkened hulk of the house. The remaining servants would be asleep inside, huddled on mattresses made of sacks stuffed with straw. No one slept in the outbuildings now, not Diggory in his dovecote or the maids in the dairy; not even Barney Curle in the servants’ yard. Only the Heron Boy kept his place in the shed by the ponds, grinning a mute refusal when Mister Bunce had tried to order him up to the house.

The figure drew nearer, his long legs striding up the incline. Making the last yards, he came to a halt before them, his face shielded by the brim of his hat. Simeon summoned his deepest voice.

‘Who comes to Buckland Manor?’

‘That depends,’ replied the man. ‘Who's its master these days?’

‘Sir William Fremantle,’ Simeon declared. ‘Same as any day.’

The man nodded then turned and gave a low whistle. Down the slope, men began to step out from the trees. Some limped. Others supported their fellows. A ragged column began to move slowly up the slope.

‘Who comes here?’ Simeon demanded again, alarmed now. ‘What's your business?’

By way of an answer the figure pulled off his hat. Simeon's eyes widened.

‘Master Saturnall!’

The ladle hung where John had left it. Lifting the handle off its hook, he touched the metal to the cauldron, the familiar tone chiming in his memory. The peal began softly, no louder than a skewer tapping the shoulder of a bottle. A faint red glow rose from the embers in the hearth. Soon the sound grew louder. Around the kitchen, heads rose from their ragged nests as the rest of the men followed John in. Then the door to Firsts swung open and a familiar stout figure entered with a rushlight.

‘My eyes! Is that Philip?’ exclaimed Mister Bunce. ‘Pandar too? Are you all back?’

‘Not all,’ Pandar responded gruffly. But his answer was lost in the noise.

The Head of Firsts clapped Luke and Colin on the back then advanced on Jed Scantlebury. Mister Stone rubbed the heads of the Gingell twins then Adam Lockyer and Peter Pears while Tam Yallop stationed himself by the door to shake the hands of all who passed. Even Barney Curle offered a grin and Ben Martin smiled reluctantly in return. The survivors of the Buckland Kitchen walked or limped into the great vaulted room where they patted the benches or gazed around at the pots and pans hanging from their hooks or simply smelt the air. All the time, John hefted the ladle, drawing great clangs from the copper.

‘Strangers in!’ declared Mister Bunce, catching sight of Ben. ‘And all the more welcome for that.’

Flanked by Simeon and Hesekey, John swung on, the metallic din rising up the hearth to resound in the flues and echo through the house. In the Great Hall, Diggory Wing and Motte uncurled and stretched. The serving men who slept in the old buttery roused themselves. Upstairs, Mrs Gardiner's head lifted from a straw-filled pillow. In chambers once swagged and draped the jangling tocsin rang brightly off the bare walls, waking the sleepers who rose and trudged in nightshirts and caps down the kitchen stairs.