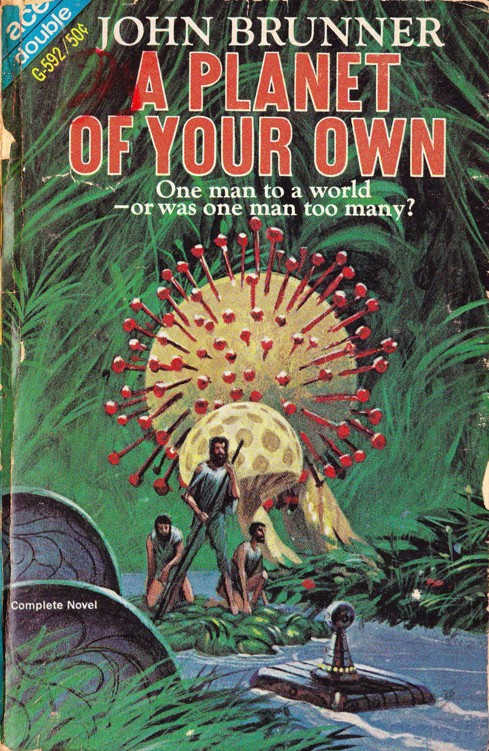

John Brunner

Authors: A Planet of Your Own

WORLDHOLD:

ZYGRA

Kynance

Foy was young, beautiful, intelligent and

highly trained in both qua-space physics and business law when she left Earth

to seek her fortune in the interstellar

outworlds

.

But she found that the further she got from Earth, the tougher became the

competition from the environment-hardened populations of these young worlds . .

. and by the time she reached the planet Nefertiti, she was facing poverty.

Then, unexpectedly, a wonderful opportunity

opened up for her: the job of Planetary Supervisor of the fabulously wealthy

world called

Zygra

, where exotic pelts costing a

million credits each were grown. The salary was huge, and at the end of the

year's tour of duty she would be transported free of charge back to Earth,

where she would be a very wealthy young woman.

There had to be a catch to it, she thought as

she signed the contract. And, of course, there was.

Turn

this book over for second complete novel

JOHN

BRUNNER

is

the author of these

outsanding

Ace novels:

TIMES WITHOUT NUMBER (F-161)

LISTEN! THE STARS! (F-215)

THE SPACE-TIME JUGGLER (F-227)

THE ASTRONAUTS MUST NOT LAND (F-227)

THE RITES OF OHE (F-242)

CASTAWAYS' WORLD (F-242)

TO CONQUER CHAOS (F-277)

ENDLESS SHADOW (F-299)

THE REPAIRMEN OF CYCLOPS (M-115)

ENIGMA FROM TANTALUS (M-115)

THE ALTAR ON ASCONEL (M-123)

THE DAY OF THE STAR CITIES (F-361)

?4

Plcuwt

by

JOHN

BRUNNER

ACE

BOOKS, INC. 1120 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10036

a planet of your own

Copyright

©, 1966, by John Brunner All Rights Reserved

Cover

art by Jack

Gaughan

.

the beasts of kohl

Copyright ©, 1966, by Ace Books, Inc.

Printed

in U.S.A.

I

T

here

was

one item on display

in the enormous window: a

zygra

pelt.

Kynance

Foy stood and looked at it. There were a lot of

other women doing the same thing.

But she was the only one

who was gritting her teeth.

It

wasn't the first time in her life she'd been the odd one out, so that figured.

For example—and the most glaring example—she hadn't

had

to leave Earth, which marked her off immediately even on a comparatively

highly populated out-world like Nefertiti. The massive "encouraged

emigration" of the Dictatrix period had lowered the premium on wanderlust

at home; it was a full generation since Nefertiti had declared

itself

independent and set quotas for

Earthside

immigrants, and then found them superfluous because the demand wasn't there.

For

the umpteenth time

Kynance

read the discreet

hand-lettered price tag attached to one corner of the stand on which the

zygra

pelt was draped. It read:

One million credits.

No other price had ever been asked for the

pelts.

Okay,

Kynance

told herself sourly.

I was

naive

....

She

had never confessed it even to her closest friends, but one of the things she

had planned to bring back when she returned to astonish those who had mocked

was—a

zygra

pelt. She had pictured herself emerging

from the exit of the starship wearing it: not elegantly, but casually, tossed

around her, her body molded by it into

insurpassable

perfection, yet her pose implying that she had had it so long she was becoming

faintly bored with the attention she attracted.

And

at this moment she did not even possess the price of a square meal.

Other plans, other ambitions, had been shed

one by one as she had doggedly worked her way towards Nefertiti, reasoning that

the closer one came to the source the cheaper the pelts might become. Not so;

only the cost of interstellar freight shrank, while the asking price remained

steady at one million.

She

stood watching the pelt's shifts of sheen and texture, wondering what exotic

perfumes it had been trained to secrete—what, for instance, matched that

liquid rainbow phase when the pelt seemed to run in endless streams of pure

color?—and cursing her own stupidity.

Yet

. . .

Could I have known better?

Oh,

maybe. Her brash confidence, though, hadn't lacked evidence to support it. She

had been fresh out of college with a brilliant record; she had deliberately

changed her major to qua-space physics and her minor to interstellar commerce

when she had made up her mind, but before that she had been well grounded in

the unfeminine combination of business law and practical engineering—the

latter by accident, merely to get even with a sneering boyfriend who had once

offered to fix her

skycar

.

This,

moreover, was not her only equipment. She was exactly five and a half feet

tall; she was exotically gorgeous, having inherited dark eyes and sinuous grace

from a Dutch ancestor who had fallen from grace in Java in the company of a

temple dancer, and hair of a curious iron-gray shade traceable only to a

colony of Cornish tin-miners totaling some five hundred persons in a

multi-billion galactic population, against which her tanned skin burned like

new copper.

There

had been no risk—so she had argued—of her ever being stranded. If the worst

came to the worst, and neither qua-space physics nor her encyclopedic knowledge

of interstellar commerce could secure her employment, she could always . . .

Well, she had never phrased the idea clearly

to herself, but it had involved some romantically handsome young starship

officer willing to hazard his career for the sake of her company on a trip to

some more promising planet, a crotchety captain won over by her dazzling

personality, and delivery with unsolicited testimonials to an entrepreneur in

need of a private secretary when they arrived.

She

had begun to suspect she had made the wrong decision on the first stop out from

Earth, when she had still had the cash to go home. What she had overlooked was

that during the miserable

régime

of the Dictatrix incredible numbers of

non-pioneer types had been—in the official terminology of the

day—"encouraged" to emigrate, chief among them intractable

intellectuals doubtful of the universal benefits Her Magnificence had

supposedly been bestowing. Consequently the

outworlds

had been colonized, forcibly, by a swarm of brilliant and

very

angry men and women. Having nothing left but the desire to get even,

they had buckled down and made the best of what they had. Not for this breed of

colonist was the broad axe or the draft-ox or the log-cabin; they were used to

lasers,

vidding

and mutable furniture, they knew the

necessary techniques, and with the determination of fanatics they had set out

not merely to provide such luxuries for themselves but to ensure that if the

same fate overtook their children or their children's children the youngsters

would be able to repeat the process.

Which was not to imply that there were absolutely no openings on such

old-settled worlds as

Ge

and New Medina for

moderately talented young women; had this been the case she would have turned

around despite the scorn she would have faced from her friends on retreating to

Earth.

Instead, she found temporary work; saved up; moved on, convincing herself

that things

would be different further out.

They

were. By her third or fourth stopover, she had been encountering sea-harvesters

supervised by ten-year-olds, each responsible for two thousand tons of

protein-rich food a week and a mainstay of the planetary economy, and reading

bulletin boards at spaceports bearing blanket warnings—to save the labor of

writing the words on every single advertisement— that no one lacking a Scholar

degree in the relevant subjects need bother to apply.

And

even her asset of last resort, her appearance, had failed her. What she hadn't

reckoned with—or had omitted to find out—was that once they had been clear of

Earth, and the traditional association of appearance with regional origins, the

emigrants whether forced or voluntary had become satisfied to be human beings

rather than Europeans or Africans or Asians. By the time a couple of

generations had slipped away, the mixing of the gene-pool had already been

producing types which made the concept "exotic" seem irrelevant:

Swedish and Quechua, Chukchi and

Matabele

, the

wildest extremes of physique met in a mad succession of paradoxes. Then,

released from

Earthside

attachment to local types,

the more prosperous girls had started to experiment, drawing on some of the

finest talents in biology and surgery. Within ten yards of where

Kynance

was standing, there were: a

Negress

with silver hair and blood-red irises, a miniaturized Celtic redhead no higher

than her elbow and very nicely stacked, and a shimmering golden girl with

slanted eyes and the quiet hypnotic movements of a trained geisha. Any of the

three would have monopolized a roomful of sophisticated Earth-men.

On Druid, somebody had asked

Kynance

to marry him. On Quetzal someone else had asked her

to act as hostess for him and be his acknowledged mistress. On Loki a third man

had suggested, in a rather bored manner, that she become his son's mistress,

the son being aged sixteen and due to submit his scholar's thesis in

cybernetics.

And on Nefertiti she would have been grateful

for even that much attention.

Confronted

with the symbol of her empty ambitions, she admitted the truth to herself at

last. She was

scared.

Well,

gawking at the

zygra

pelt wasn't solving the problem

of hunger. She started to move away.

At

that moment, a soft voice emanated from the air. It came over a biaxial

interference speaker, so for practical purposes the statement was exact. She

stopped dead.

"The

Zygra

Company draws your attention to a vacancy

occurring shortly in its staff.

Limited service contract, generous

remuneration, comfortable working conditions, previous experience

not

necessary,

standard repatriation clause.

Apply at this office, inquiring for

Executive Shuster."

The

message was repeated twice.

Kynance

stood in a daze,

waiting for the rush to begin. There was no rush. The only reaction was the

sound of an occasional sarcastic laugh as people who had been gazing at the

pelt were disturbed and decided to wander on.

No.

Ridiculous.

Impossible.

She must

have dreamed it. Not enough food and too much worry had conspired to make her

mind play a trick.

Nonetheless

she was on her way to the entrance of the

Zygra

Building. She hadn't made a conscious decision—she was following a tropism as

automatic as that of a thirsty man spotting an oasis across the desert. She did

wonder why one or two people she jostled looked pityingly at her eagerness, but

that was afterwards.