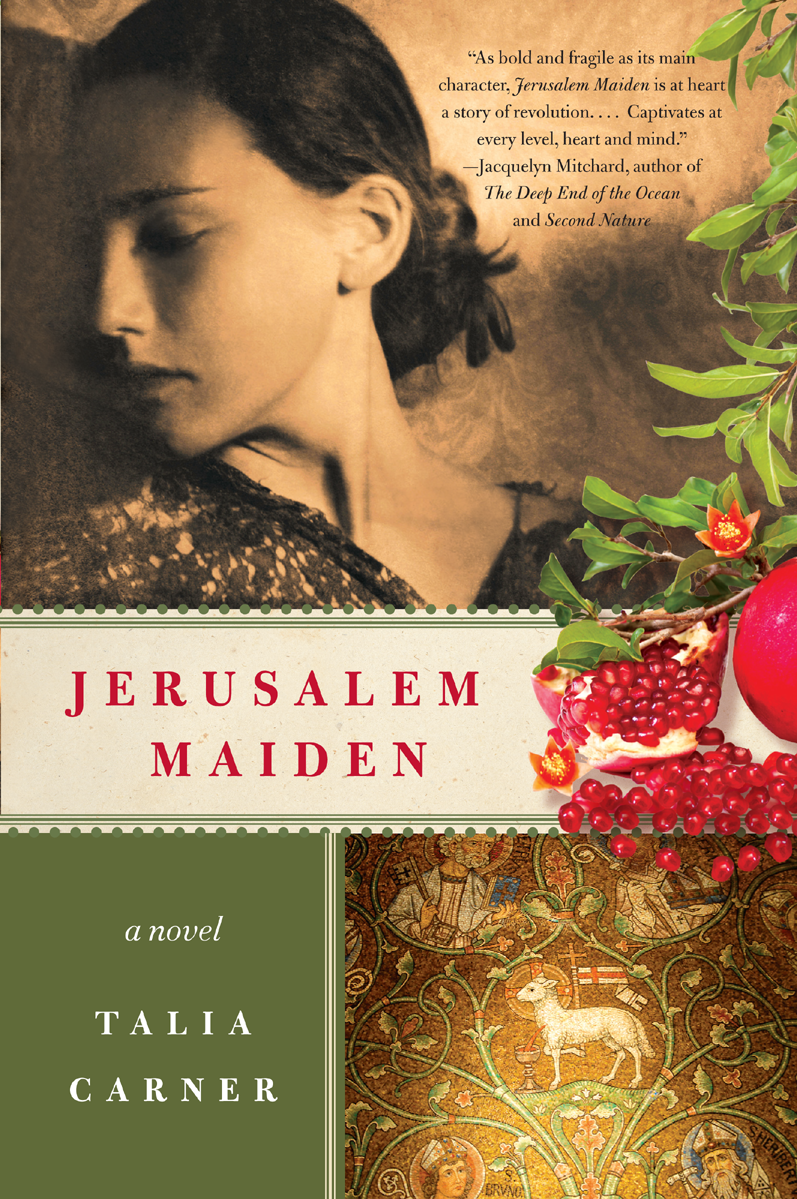

Jerusalem Maiden

Authors: Talia Carner

Jerusalem Maiden

A Novel

Talia Carner

T

O MY GRANDMOTHER,

Esther (Yanovsky) Lederberg, 1900â1980,

FOR YOUR UNTAPPED GENIUS

AND UNFULFILLED DESTINY.

Contents

Â

Â

OCTOBER 1911/HESHVAN 5672

Â

DECEMBER 1911/TEVET 5672

Â

JANUARY 1912/SHVAT 5672

Â

FEBRUARY 1912/ADAR 5672

Â

MARCH 1912/NISAN 5672

Â

APRIL 1912/IYYAR 5672

Â

JUNE 1912/TAMUZ 5672

Â

JULY 1912/AV 5672

Â

Â

NOVEMBER 1914/HESHVAN 5675

Â

DECEMBER 1914/KISLEV 5675

Â

JANUARY 1915/TEVET 5675

Â

FEBRUARY 1915/SHVAT 5675

Â

MARCH 1915/ADAR 5675

Â

APRIL 1915/NISAN 5675

Â

Â

Jaffa -

APRIL 1924/NISAN 5684

Â

MAY 1924/IYYAR 5684

Â

JUNE 1924/SIVAN 5684

Â

Paris -

JUNE 1924/SIVAN 5684

Â

JULY 1924/TAMUZ 5684

Â

Â

AUGUST 1924/AV 5684

Â

SEPTEMBER 1924/ELUL 5684

Â

DECEMBER 1924/HESHVAN 5685

Â

Â

E

sther's hand raced over the paper as if the colored pencils might be snatched from her, the quivering inside her wild, foreign, thrilling. All this time she hadn't known that “blue” was actually seven distinct shades, each with its own nameâazure, Prussian, cobalt, cerulean, sapphire, indigo, lapis. She pressed the waxy pencils on the paper, amazed by the emerging hues: the ornaments curving on the Armenian vase were lapis; the purplish contours of the Jerusalem mountains were shrouded by indigo evening clouds. In this stolen hour at Mademoiselle Thibaux's dining-room table, she could draw without being scolded for committing the sin of idleness, God forbid.

A pale gecko popped up on the chiseled stone of the windowsill and scanned the room with staccato movements until it met Esther's gaze. Her fingers moving in a frenzy, she drew the gecko's raised body, its tilted head, its dark orbs focused on her. She studied the translucency of the skin of the valiant creature that kept kitchens free of roaches. How did God paint their fragility? She picked up a pink-gray pencil and traced the fine scales. They lay flat on the page, colorless. She tried the lightest brownâ

Her hand froze. What was she thinking? A gecko was an idol, the kind pagans worshipped. God knew, at every second, what every Jew was doing for His name. He observed her now, making this graven image, explicitly forbidden by the Second Commandment,

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.

With a jerk of its head, the gecko darted away. Esther stared at the paper, her hand in midair. She had never imagined a sin like this.

Mlle Thibaux walked in from the kitchen nook, smiling. Her skin was smooth, luminous, and her brown hair uncovered, its coquettish ripples pinned by twin tortoiseshell combs. She picked up Esther's drawing and examined it. “

C'est merveilleux! Quel talent!

”

Esther blushed. The praise reflected what Mlle Thibaux's raised eyebrows had revealed that morning in sixth-grade French class when she had caught Esther doodling. To Esther's consternation, her teacher must have detected the insects hidden inside the branches and leaves. The teacher turned the page this way and that, and her eyes widened. She then asked Esther to stay after school, and Esther was certain she would be ordered to conjugate the verb “to be” hundreds of times on the blackboard:

je suis, tu es, il est, elle est

â Instead, Mlle Thibaux invited her to her apartment at the Hospice Saint Vincent de Paul, a palace-like building with arch-fronted wings, carved colonnaded verandas and balustraded stairwells. The teacher was a

shiksa

, a gentile. Newly arrived from Paris, she probably didn't know that while it wasn't forbidden in Esther's ultra-Orthodox community to decorate with flourished letters and ornamental shapes, drawing God's creatures was another matter.

Now, holding Esther's drawing, Mlle Thibaux smiled. “Here, try mixing these two colors.” On a separate page, she sketched a few irregular lines with a pink pencil, then scattered some short leaf-green lines in between.

Esther chewed the end of her braid. Fear of God had been instilled in her with her mother's milk and in the Ten Commandments tablets displayed everywhere, from her classroom to the bakery. In addition, the Torah pronounced that any urge must be suppressed, as it would surely lead to sinning. The quickening traveling through Esther again proved that what she was doing was forbidden. Her mother said that Esther's harshest punishment for sinning would be failure to become betrothed at twelve, as every good Jerusalem maiden should upon entering her mitzvah age. Yet, as Mlle Thibaux handed her the pink and green pencils, Esther silently prayed for God's forgiveness and recreated the hues inside the gecko's scales. To her astonishment, they blended as a translucent skin.

A knock sent Mlle Thibaux to the door, her back erect and proud as no woman Esther had ever known. The teacher accepted a pail from the water hauler and carried it to the kitchen while Esther collected the pencils into their tin box.

Outside the window, slicing off the top of the Tower of David, a cobalt-blue sky hung low on the horizon like a wedding

chupah

with a ribbon of magenta underlining it. A flock of sparrows jostled for footing in the date palm tree, then rose in a triangular lace shawl formation before settling again. The warm smell of caramelized sugar wafting from the kitchen made Esther hungry for tonight's dinner, a leftover Shabbat challah dipped in milk and egg, fried and then sprinkled with sugar. Closing the pencil box, her hand traced its scene of a boulevard in Paris, lined with outdoor cafés and their dainty, white, wrought-iron chairs. Women wearing elegant hats and carrying parasols looped their arms through men's holding walking sticks, and the open immodesty of the gesture shocked Esther even as it made something inside her tingle. In Jerusalem, only Arab men, dressed in their striped pajamas, idled on low stools in the souk and played backgammon from sunrise to sunset. Their eyes glazed over as they sucked the mouthpieces of hoses coiled around boiling tobacco narghiles. Paris. Esther had never known a girl who traveled, but when she had been little, her father, her Aba, apprenticed at a bank in America. It was a disastrous exposure to “others,” her mother, her Ima, said, because it filled his head with reprehensible new ideas, worse than the simpleton Hassids'. That was why Aba sent his daughters to a school so elegant that Yiddish was frowned upon. Most subjects were taught in English, and Esther mingled there with Sepharadi Jewish girls who spoke Ladino and Arabic as well as with secular girlsâheretic Zionists all of them, Ima saidâwho spoke the sacred Hebrew.

“

Chérie

, will you light the candles?” Mlle Thibaux walked in from the kitchen nook and placed a silver tea set on a spindle table covered with a crocheted napkin. The high collar of her blouse was stiff over starched pleats running down the front to a cinched waist, but when she moved, her long skirt immodestly hinted at legs. Had she ever walked in Paris with a man, daring to loop her arm in his?

Mlle Thibaux smiled. “It's four o'clockâ”

Four o'clock? Esther's hand rose to her throat. Ima, who expected her to attend to her many chores right after classes, had been laboring alone while Esther was indolent. Ima would be furious. “I must go homeâ”

Mlle Thibaux pointed to a plate with slices of glazed cake sprinkled with shaved almonds and cinnamon. “It's kosher.”

“

Non, merci.

The neighborhood gates will get locked for the night.” Saliva filling Esther's mouth, she gathered her long plaid skirt and backed toward the door. She had never tasted a French cake; it had been ages since she had eaten any cake. But Mlle Thibaux's kitchen was

traife

, non-kosher. Esther wouldn't add another sin to her list. “

Merci beaucoup!

”

She ran out of the apartment, down the two flights of steps, and across the stone-paved yard to the street facing the Jaffa Gate in the Old City wall, where camels awaited pilgrims and Turkish soldiers patrolled. Restless birds chirped in desperation to find shelter for the night. Wind rustled the tops of the tall cypresses and whipped fallen leaves into a spin. Maybe it would rain soon, finally replenishing the dry cistern under her house.

Running downhill, she turned north, her sandals pounding the cobblestones. At least she wasn't barefoot as she had been that morning, putting her sandals on at the gate to Evelina de Rothschild school to save the soles. She vaulted over foot-wide sewage channels dug in the center of the alleys. Then there was the open hill with only rocks and scattered dry bushes flanking the dirt path grooved by men, carts and beasts. Climbing fast up the path, she listened for sounds beyond the trilling of crickets and the buzzing of mosquitoes. In the descending darkness, a Jewish girl might be dishonored by a Turkish soldier or murdered by an Arab. Just on the next hill, the grandfather she had never met had been assassinated while inspecting land he purchased for the first Jewish neighborhood outside the Old City.

A scruffy black dog stood on a rock. Esther's heart leaped. Dogs were despicable creatures; they carried diseases that made people insane. It growled and exposed yellow-gray teeth. When Esther swerved out of the path, it gave chase. She screamed, running faster, the dog barking behind her. She grabbed the hem of her skirt, and her feet pounded on rocks, twisting, stumbling. If she tripped, she'd die. Now that the Ottoman Empire was crumbling and the sultan neglected his subjects, hungry Jerusalemites ate even rotting scraps of food, and starving dogs bit people. The Turkish policemen killed dogs on sight.

Was that the dog's breath on her heels? She gulped air. Her wet cheeks were cold in the rush of wind. A blister burned the sole of her foot. The dog must smell her sweat, her fear. She couldn't outrun it. Her punishment for drawing idols had come so soon! It had never occurred to her that there could be a fate worse than Ima's warning about failing to find a groom. To Esther, that threat had always sounded like a blessing.

Cold pain sliced her rib cage, and her lungs burned. She could run no more. She stopped. Whirling, she faced the dog, exposed her teeth and snarled, waving her arms like the mad girl she'd become if it bit her.

To her amazement, the beast halted. Another snarl rose from Esther's chest, tearing her throat, and the animal backed off. She flailed her arms again, and the dog tucked its tail and slunk away.

Her heart still struggling to escape its confinement, Esther whispered a prayer of thanks and then fumbled for the amulet in her pocket to stave off the evil eye. Her pulse drummed in her ears. She broke into a trot. Five more minutes to Me'ah She'arim. Her inner thighs chafed over her belted socks, but stopping wasn't an option. Wicked windsâworse than dogsâgusted in search of a soul deserving punishment, one that had defied God.

P

anting, Esther was about to enter the tiny kitchen yard of her home, when she was startled by a movement in the shadow. Lilith the ghost? It was common knowledge that she stalked the night. Or what if these were the robbers Ima fretted about? Or Turkish soldiers raiding the Jewish streets to kidnap boys for lifelong military service, as Aba feared? Esther held her breath as if she could become invisible, then jumped at the screech from the rusty neighborhood iron gate swinging shut.

A figure stepped into the patch of yard washed by the last light of dusk: her friend Ruthi.

“You scared me,” Esther said in Yiddish, grabbing Ruthi's hand. “What happened?” She scanned the large rectangle of communal space created by rows of identical one- and two-room houses clinging together like a frightened herd of goats. Their back walls bordered the thoroughfare to form an impenetrable blockade. In the center, the oven, the well, the laundry shed and the outhouses were all dark and silent, as were the yeshiva and the

mikveh

. Only the synagogue's windows shone, where the silhouettes of praying men would sway until the wee hours as they mourned the destruction of the Temple nineteen hundred years earlier. “Did someone die?” Esther asked. After the recent Day of Atonement, God might have struck a wicked manâor even a seemingly virtuous nursing mother.

“Did you take a ride in Elijah's chariot?” Ruthi asked. A smile broke on her face and she gushed on. “Guess what? I am going to be betrothed! Blessed be He.”

“And I'm the rabbi marrying you,” Esther said in a ponderous tone and stroked an imaginary beard. She and Ruthi had made a pact to refuse marriage until they finished school. She wanted to report about her afternoon at Mlle Thibaux's, but right now she had to get in the house. Resuming her own voice, Esther motioned toward her kitchen yard. “Come in. I have work to doâ”

“Well?” Ruthi asked.

“Well what? I'll beat you at hopscotch tomorrow.” They kept a running tally, and that morning Ruthi had taken first place.

“I can't play. Not now that I'm an adult.”

The rising moon illuminated the delicate line of Ruthi's thin nose and heart-shaped mouth. If she had Mlle Thibaux's colored pencils now, Esther thought, she would highlight Ruthi's clear skin with lavenderâ

“

Nu?

Well?” Ruthi demanded.

The fact suddenly penetrated Esther's head with the sounds of the neighbors' clattering pots and pans, the cries of babies, the scratching of furniture being dragged to make room for cots, and the angry thumping of Ima's wooden clogs on the chiseled kitchen floor. “But, butâMiss Landau said we shouldn't get married before fourteen, or even sixteenâand you agreedâ”

“That's ridiculous. Name one religious girl in school who's waited that long.”

“I will,” Esther said, even though Aba often explained that marriage was the Haredi community's building block, especially in Jerusalem, the holiest of all cities, where a maiden carried the promise of perpetuity for all Jews in the entire universe.

“My groom is a biblical scholar,” Ruthi said.

“All these yeshiva

boochers

are afflicted with hemorrhoids from sitting on hard benches all day and all night.”

“I'm serious,” Ruthi said. “Marriage will make me important.”

The amulet in Esther's pocket felt cold. “You'll work your fingers to the bone from dawn to midnight, you and the children starving, barefoot, and living off charity, while he studiesâ”

Ruthi's eyes widened in shock. “It will hasten the Messiah's arrival.”

Esther knew that her utterings were Zionist blasphemy, but the subject of betrothal had never hit this close before. “Do you want to be responsible for the future of all Jews?” she whispered.

Ruthi stamped her foot. “Just say

mazal tov

.”