Jerry Langton Three-Book Bundle (27 page)

Read Jerry Langton Three-Book Bundle Online

Authors: Jerry Langton

When attempts to negotiate with the Texans failed, Muscedere wrote begging messages on the guestbooks of Bandidos' sites around the world, appealing to them to stand up for the Toronto Chapter, which Muscedere claimed was being treated unfairly. Nobody â not even their Scandinavian sponsors â came to their aid, or if they did they were quiet about it and not very successful.

Finally, Muscedere sent the following e-mail to every Bandidos chapter in the world:

We ask that our Brothers make there voice heard from all over the world and stand tall with us in support of us as we have all our brothers. We would like a worldwide vote from all our brothers from around the world before we return our Bandidos property.

The highest-ranking member of Bandidos, el presidente Jeff Pike from the Houston Chapter, had the final word on the matter when he sent an e-mail to Muscedere that told him: “Bandidos don't vote, they do what the fuck they're told.”

Although they kept their Bandidos patches, the Toronto Chapter (many of whom, like Muscedere, actually lived in Southwestern Ontario and commuted to the club meetings) renamed themselves the No Surrender Crew, a name borrowed from a particularly violent faction of the Irish Republican Army. The Toronto version of “No Surrender” referred to the fact that these Bandidos wouldn't give up their patches without a fight.

Kellestine was a different story â as he always seemed to be. With some excessive drug use and bad business ideas, he had gone into severe debt, and one of his biggest creditors was the club itself. He had also forged a bitter divide between himself and the rest of the club by complaining bitterly of their lack of desire to make money and because they always called him late for meetings, not taking into account how far away he lived. And he had made some new friends outside the club. The crystal meth trade was flourishing and growing in Southwestern Ontario, and Kellestine had acquired several close associates in the business of manufacturing and retailing the drug. They assured him it was easy money, exactly what he needed to get out of his money troubles. Still, Muscedere and the bulk of the Toronto Chapter did not want to get involved with Kellestine's new friends or their business. It was, they decided, just too dangerous.

But some others did want to get involved. Kellestine had reached out to Winnipeg's prospective Bandidos, who lived in a place where meth had been very popular for a much longer time. The members of the probationary chapter there had grown very impatient with Muscedere, whose incompetence and poor relationship with the Texans they felt was the real reason they had been prevented from getting recognized as an independent full-patch Bandidos chapter.

At the start of April 2006, it all came to a head. The Americans had ordered Muscedere and his men to relinquish their patches more than five months earlier. But the No Surrender Crew were determined to stay on as Bandidos anyway, and wanted to do it without Kellestine and his meth. Kellestine wanted to make money selling meth and, if possible, remain a Bandido. Winnipeg wanted to be Bandidos making money selling meth and saw Muscedere and his crew standing in the way.

The Americans had given Kellestine the task of collecting his chapter's patches and returning them to Texas in March 2006. The job was too big for him, and he knew it. So he stalled. But when four representatives of the Winnipeg prospective chapter arrived unannounced at his Iona Station farm to ask him why he hadn't stripped his brothers of their patches (strongly intimating that they'd pull his own patch unless he acted quickly), he knew he had to do something.

The Winnipeggers were tough guys, sent on purpose to intimidate Kellestine. The tacit message was that if he didn't take care of it, they would do it themselves and they would take care of him, too.

Besides being a former cop and martial arts instructor, Sandham had been in the Canadian military, had undergone special-weapons training and had been known to associate with members of the Winnipeg Outlaws. He was easily the most important member of the prospective chapter and president-in-waiting should Winnipeg ever become a full-patch chapter. But the members of his gang were pressing him to do something about Toronto, and he, too, was in danger of losing his status among them unless he acted.

Sandham was actually with Kellestine at a March 2006 meeting with the American Bandidos at the Peace Arch Park on the British Columbia-Washington state border when the original orders to pull Toronto's patches came down. The park is unique in that there's a picnic table there that allows people on opposite sides of the border to meet face to face without entering the other country. This is important to bikers of many clubs because many of them are banned from crossing the border due to felony convictions or outstanding warrants.

The orders to “unpatch” the No Surrender Crew came from Peter “Mongo” Price, a 350-pound monster with long hair he liked to dye a brilliant shade of orange. Price was the Washington State Bandidos sergeant-at-arms, and was known to carry two guns, two knives and a chain with him at all times. He is said to have told Kellestine that if he succeeded in removing Toronto's patches he would be in charge of the Toronto chapter and be Canadian national president, while Sandham would become president of the newly official Winnipeg Chapter, and second-in-command of the Canadian Bandidos. He also indicated that if Kellestine failed, he would be in the same boat as the rest of the Toronto chapter and the duty (and rewards) would then fall to Sandham.

Police recorded Kellestine talking to Keswick-based full-patch Cameron Acorn just after the meeting. He told him that “The people in the States are super, super, super fuckin' choked.” In biker parlance that means upset or disturbed. When Acorn acknowledged that he knew that, and that Kellestine had been out west to talk with them about the situation, Kellestine told him: “And don't say a word, just ... uh ... just leave it at that.”

Later in the same phone conversation, he told Acorn that there was trouble on the horizon: “For some strange reason they [the Americans] seem to ... oh, fuck ... anyways there's gonna be some major changes, man ... I'm telling you that right now you protect yourself ... it's not my doing, I want no part of this, but I'm gonna try to salvage as many guys as possible.”

When Sandham arrived at Kellestine's farm, he brought along full-patch Dwight Mushey â a former kick-boxer turned boxer who had a rather disheartening 7-32-1 record as a pro. He had already been arrested for selling meth at least once back in Manitoba. Also with them was prospect Marcello Aravena â a professional tae kwon do instructor and strip-club bouncer. There was another man in the group, another big guy, Mushey's workout partner who was a full-patch and is now in the federal witness protection program and may only be referred to as M.H. He was a police informant before April 2006, but did not have any significant information about the upcoming meeting to share with police.

The four men showed up, they said, at the urging of an American Bandido who was identified as Keinard “Hawaiian Ken” Post. Post wanted to know why it had taken Kellestine so long to pull Toronto's patches.

Instead of just giving up and allowing the Winnipeggers to pull his patch, Kellestine explained his situation and recruited them to help him and two local friends â career break-and-enter man Frank Mather, who was originally from New Brunswick but now lived with Kellestine, and 21-year-old Brett “Bull” Gardiner of no fixed address â to strip Muscedere and his men of theirs.

Chapter 13Bloodbath at 32196 Aberdeen Line

Kellestine's visitors must have noticed that the first floor of his house at 32196 Aberdeen Line was decorated entirely in red and black, with swastikas, Iron Crosses and other Nazi memorabilia all over the place. He was obsessed with two things â guns and the Nazi party.

And he wasn't the only one. Kellestine's self-confessed “right-hand man” was a local character and truly massive full-patch Bandido named David “Concrete Dave” Weiche. He earned his nickname from his work at his father's immense contracting firm. And his father â Martin K. Weiche â wasn't just well known because he was wealthy and successful. The elder Weiche, like Kellestine, decorated the family house with Nazi memorabilia, including oil paintings of Adolph Hitler and an autographed copy of

Mein Kampf

, Hitler's autobiography.

Mein Kampf

, Hitler's autobiography.

Virulently racist and thoroughly atavistic though they may have been, at least the elder Weiche came by his views somewhat honestly. He had been in the Hitler Youth and had fought for the Nazis in World War II. After emigrating to Canada and becoming very successful, he ran in the 1968 federal election in the riding of London East as a National Socialist. The word “Nazi,” it's important to note here, is actually a short form of the German phrase “Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei,” which means “National Socialist German Workers' Party” and was the official name of Hitler's organization.

Under that red-and-black banner, Weiche received 89 votes. He was later connected to some violent clashes, a couple of local cross burnings and was alleged to have put up the money for Operation Red Dog â a failed coup attempt in Dominica, which was aimed at establishing a white supremacist government on the small Caribbean island after expelling all of its black residents.

Although the younger Weiche had been at the Peace Arch meeting with Kellestine, Sandham and Price, he had left Southwestern Ontario for Winnipeg about three months before Sandham and his crew showed up at the farm. There has been no evidence to indicate he had any involvement with or even any knowledge of what happened next.

Many locals who had no connections to outlaw motorcycle gangs knew about Kellestine's attitudes. He had a habit of doing things like interrupting London's annual Pride Day Parade by dancing around with the Confederate war flag (the familiar stars and bars) â but only, he told friends, because he could be indicted if he used a Nazi flag; he considered the Confederate flag to be a decent second choice.

His racist and anti-Semitic views were well known, but they were not considered bad enough to get him thrown out of or even disciplined by the club. Some sources have told me that, while his beliefs may have been flamboyantly displayed, they were hardly rare in his milieu.

But they caused some friction in Toronto. Because, while Kellestine was a constantly stoned, frequently violent arrest-waiting-to-happen, the club had a few promising prospects like Jamie “Goldberg” Flanz. His friends called him “Rogue,” but the Bandidos, particularly Kellestine, usually called him “Goldberg.”

Originally from Montreal, the strapping former hockey player was a well-liked and intelligent young man, but he had a habit of breaking laws. He was the son of a well-known and well-heeled Montreal lawyer and something of a computer expert. In 2003, Flanz had been hired by a big American company, but was fired because he had set up a website that was in direct competition with the one they paid him to establish. His wife left him, and nobody in the computer business was interested in hiring him. So, he took a job as bouncer at a bar in Bradford, Ontario, (about an hour north of Toronto) and lived in nearby Keswick.

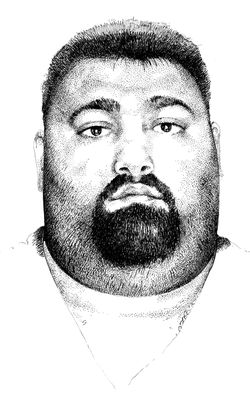

Jamie “Goldberg” Flanz

Although Keswick had been a Hells Angels' stronghold since the mass patch-over, the muscular Flanz shaved his head, grew a goatee and started running with the Bandidos. Police were well aware of it, too. When they found the beaten and burned body of Keswick-native Shawn Douse in Pickering on December 8, 2005, they arrested four Bandidos (two of whom were already in jail on other charges) and searched Flanz's apartment. Douse was known to have been an active cocaine dealer, and was seen at a meeting at Flanz's apartment earlier that week. They found no evidence of his involvement and Flanz was never charged.

As charming as Flanz could be, Kellestine hated him. Everybody knew that it was because he was Jewish. And so, at the start of April 2006, when Kellestine accused Flanz of being an informant, Muscedere and his crew attributed it all to Kellestine's rabid anti-Semitism and his growing paranoia. So when he invited them to his farmhouse in Iona Station to discuss the matter, they agreed. Their plan was not to entertain Kellestine's wild accusations, but to kick him out of the club.

So on Friday, April 7, 2006, the Toronto Bandidos, other than Kellestine himself and two others who were out of town, drove down the 401 from Toronto to Iona Station to meet Kellestine and the Winnipeg prospective chapter. Both sides were determined to take the patches of the other.

Paul “Big Paulie” Sinopoli

Other books

Engaged in Embellishments: Tulle and Tulips, Book 5.5 by Nikki Duncan

Blood and Ashes by Matt Hilton

Lethal Legend by Kathy Lynn Emerson

Taming a Highland Devil by Killion, Kimberly

Beloved LifeMate: Song of the Sídhí #1 by Cooper, Jodie B.

The Jack the Ripper Location Photographs: Dutfield's Yard and the Whitby Collection by Hutchinson, Philip

Wintercraft: Blackwatch by Jenna Burtenshaw

Sinfully Yours by Cara Elliott

Fear and Aggression by Dane Bagley

MeltMe by Calista Fox