Jellied Eels and Zeppelins (10 page)

At The Elms cricket ground at the back of where I lived, there were playing fields and the River Lea beyond, where there were horse-drawn barges. The Germans dropped a load of bombs there, ‘cos they thought it was the Thames - it stretched almost to Edmonton. So, when we were in the dugout during a heavy raid, we were being shaken about through the impact of the bombs exploding. Your head resounded with the ‘Bang! Bang!’ as you sat there with your feet in water. After the war was over, I think that about four to five hundred unexploded bombs were found there.

There were Molotov baskets (Incendiary Bombs) and they used to come down all alight and you could only put sand on them to put them out. Land mines, rockets, buzz-bombs - we had the lot!

I was sitting in front of the cooker crocheting once when the air raid warning sounded. Mum said ‘I’m not going in the dugout tonight - I’m fed up sitting with me feet in water.’ All of a sudden, we heard an explosion, flew up the passageway and got down on our knees. Mum was in front and me behind, we were almost lying down. We could hear another one coming and as we listened, I looked at my hand - my crochet hook was just inches away from my Mum’s bottom! I’ll never forget that as long as I live.

We sat in the dugout and Dad would say he was going for a walk to make sure everyone was all right. If people were frightened and a bit nervous, he’d go and talk to them and all that sort of thing, you know. He was very good and got a medal for it, ‘cos I found it in one of his drawers when he died.’

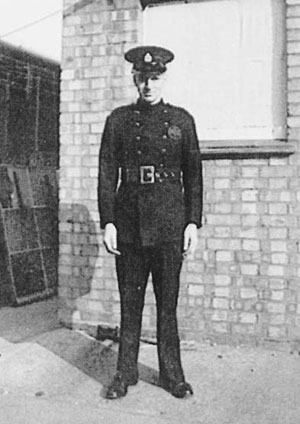

1942: Joe in his NFS uniform

Joe, for his part, joined the National Fire Service (NFS) after failing his medical for the services because of a leg injury. He completed his training at Forest Road Fire Station in Walthamstow and was the leading fireman at Ensign, where he made, repaired and inspected air force cameras:

‘He fell down the iron staircase, where he worked and twisted his leg two weeks before his number was called up for the Air Force. They made you stand on one leg and swing the other and he couldn’t stand on his bad leg, so they asked him to come back in three months time. During those three months, they dropped his age group (he was six years older than me) so he had a choice of going in the Fire Service or the Home Guard. Where he worked at Ensign, they wanted him in the fire service, so he chose that which meant that he could do a bit of work as well as be a fireman.

Joe loved his fire service. I remember later, when we came to Doddinghurst and the chimney caught alight, he knew just what to do - he took out all the front and stuck wet sacks up it. It was when I had an Aga and it was Christmas morning and I was cooking me chicken in it and it made the chimney breast red hot upstairs. And he knew what to do - he was really clever.

He never really said anything about his fire service work, except when a bomb dropped on Ensign on the place where they kept all the liquids, spirits and that for the work. It all caught alight and he got his shoes burnt… his feet got red hot, but, as he was leading fireman, he had to stand there you see. He used to tow this big tender with a truck. Directly the siren went he was on duty. We used to come down to Doddinghurst sometimes for a sleep in the shed to get away from all the noise, though we weren’t supposed to. You weren’t supposed to come out of your area if you were a fireman, but we didn’t do it often.

Because the work I was doing at Ensign was classed as luxury trade, they closed down our floor, which is why I went into ammunitions. I was the last one to go.

Colleagues at the munitions factory, Walthamstow

I also worked as an inspector in a munitions factory in Billet Road, Walthamstow, where I oversaw the making of tracer bullets and gun parts. I used to do a fortnight of days and a fortnight of nights. I was there when I got married. I was there for about a fortnight and they put me on as inspector. I used to set all the machines up in the morning or at night. I loved it. I would inspect all the little parts that went in the bombs and we assembled them. I used to have to check them all and check the girls to make sure they did their work.

I was paid by the Woolwich Arsenal by cheque once a month through the Post Office. They got me the job at the Labour Exchange. I had to have an examination by a doctor before I went there and I had to make a will to say what I was going to leave to my Mum. In the middle of a raid, we used to have to rush out and go into the dugout, where I would sit crocheting.

When I was on nights, I would work from eight at night ‘til eight in the morning. When I was on days, it would be from eight in the morning ‘til eight at night for another fortnight. And I also made ammunition boxes for Cabinet Industries Ltd on the Arterial Road, with Cousin Flo.’

Roses and Wedding Cakes

‘I didn’t leave Mum ‘til I was 30, ‘cos I loved her so much. I had my wedding dress made by old friends of ours, who were court dressmakers up in London, and my sister’s bridesmaid’s outfit - her dress, headdress, her gloves, shoes, everything - she was my matron of honour. I was going to have a little one to hold my train. She was three, but her mother had to go away, because they evacuated mothers who were expecting babies.

I bought all the flowers, even the buttonholes, as well as the wedding breakfast. It was with the money I’d saved since I was a toddler. The only thing I borrowed, was my sister’s wedding veil. We went and saw a bedroom suite we wanted in Hoe Street and we hadn’t got quite enough money - we wanted another £3, I think it was. So my Dad said ‘I’ll loan you the £3, but I want it back,’ so I went and paid for it and got it delivered to our flat, and I paid my father back with my first week’s wages afterwards.

My father grew us some flowers on his allotment and we had those on the tables. The flowers in my bouquet came from Alda’s florist in Hoe Street. I remember my bouquet cost £2 and 10 shillings and my sister’s was £1 and 10 shillings. My bouquet consisted of red roses and white heather and Florrie wore a dress of lavender and her bouquet was all lovely tea roses.

Ethel and Joe’s wedding. September 1940. Florrie was bridesmaid and Joe’s brother best man

When we were standing at the altar, the warning went and the bombs were dropping. We couldn’t have the church bells and we couldn’t have the choir, because they had all been evacuated, so all we had was the organ.

Oh, and I’ll never forget it. I’ll tell you what happened. It was a High Church, St. Michael’s and All Angels mind, and they burnt incense in there. There was a man who waited at the door to lead you in. He was a little man in a little hat with a knob on the top. I was holding my Dad’s arm and we were walking up the aisle and this little man tripped and I had a fit of the giggles and couldn’t stop laughing. Because I couldn’t have little Jean holding my train, I’d sown a tape onto my train and held it on my little finger. When I got to the church, I let it go down. As we got to the altar - you have to walk up two or three steps to get to the altar - I remembered seeing in a film once at the pictures, one woman standing on some else’s train and pulling the back out. I was standing at the altar thinking of that - I don’t know why - and I said to my chap ‘When you move, don’t tread on my train!’ And he did just that. I whispered ‘Get off! Get off!’ When I got home and looked, I had footmarks right in the middle of me train. I never forgot that. There was three, if not four yards, of material in the train.

Later on, brides were unable to buy traditional wedding dresses with trains because the amount of material they required had been rationed

.

I had one of those collars that stood up at the back, stiff, Queen Anne style, and all little buttons along the sleeves, which came down in points over my hands. And, at the bottom, I had a little frill, all the way round. And I had a twisted silver cord around me waist with tassels.

When my sister got married, my mother waited at the tables. When I got married, I said ‘You don’t do that. You’re equal to us.’ My Mum was lovely. She bought a big tin of ham. She cooked sausages and all that and sliced them. We had jelly and blancmange, you know. She bought the stuff and stored it before the wedding. And the lady upstairs waited on the tables. We all sat down. I borrowed the trestles and the stools from the church around the corner and brought them round to our home on a trolley. I managed to buy the last white wedding cake from Hayes, the baker - he was one of the old-fashioned bakers. It was a two-tier one. One of the girls from upstairs, Mary, who got married after me, had to have a chocolate one, ‘cos I went to her wedding. (

Many later had to make do with cardboard wedding cakes

). Everybody went home at nine o’clock because of the air raids.

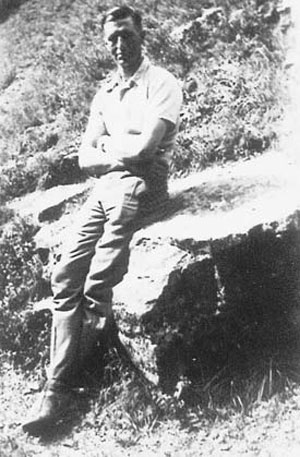

1940: Ethel on honeymoon at Cheddar Gorge

I got fish knives and forks and my chap got a bedside lamp as wedding presents. The lamp was all crystal pink. I had been due to collect a wedding present from some ex-neighbours of ours. I had visited them some two weeks before and it had been time for me to leave, ‘cos I had to catch the tram in order to be home on time.

Unfortunately, the bus was late - probably due to an air raid - so I ran all the way from my stop home all in the pitch black, because I knew I would be in trouble with Dad for being late. I arrived home with one minute to spare, completely breathless. Dad was sitting in the front room with his watch in hand! I later discovered that the family I had been visiting, had been killed by a bomb, which dropped on their house while they were sheltering in the cellar. The girl was a pretty little thing. I used to push her in her pram when she was little. She had wanted to be a bridesmaid at my wedding.

We got married on the Saturday and went back to work on the Monday, though we did have a few days honeymoon in Cheddar Gorge a little later - by motor bike, of course.’

It was to be one of their last outings for a while, for Joe had to sell his bike because of the petrol rationing. In 1942, people had to prove that driving was essential to either their work or health, in order to obtain petrol coupons.