January Window (28 page)

Authors: Philip Kerr

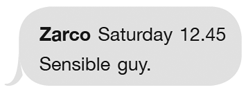

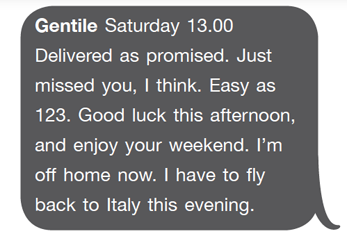

There were no texts from Zarco after 12.45 p.m. and, according to Phil Hobday, Zarco had left the director’s dining room at around 1.05 p.m., after which he hadn’t been seen alive again. Where had he gone after that? It was impossible to imagine him being forced to go somewhere against his will without someone noticing. Zarco’s face was in a thirty-foot-high mural on the side of the stadium. He wasn’t exactly anonymous. Surely someone must have seen him.

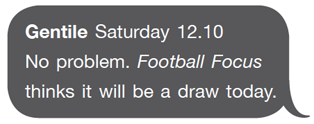

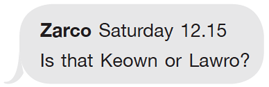

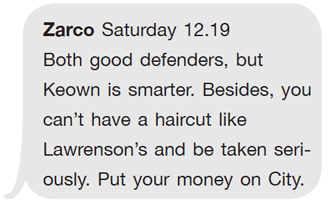

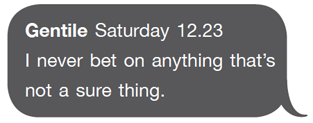

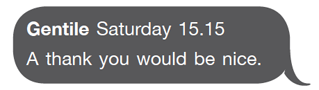

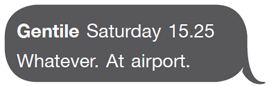

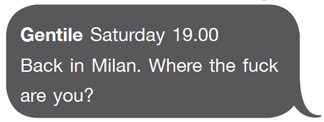

These texts begged several other questions, too: if Paolo Gentile had brought a fifty grand bung to Silvertown Dock and left it hidden somewhere for João Zarco, where was it now? Was it even where he had left it? After all, fifty grand is a pretty good reason to beat someone up and rob them. Unless of course he hadn’t brought it at all, and they’d quarrelled again. Wasn’t it possible that the texts Gentile had sent to Zarco after 1 p.m. had just been a cover? And where better to be now that the police were investigating Zarco’s death than safely at home in Italy?

On the other hand, maybe Toyah was right after all, and Zarco had good reason to be afraid of Viktor – a better reason than even she knew. Just what would Viktor have done if he’d found out that Zarco had bought shares in SSAG on an insider tip?

In the hope of learning more – what was 123? Who were the guys he’d needed the fifty grand for? Could they have been sufficiently pissed off at Zarco to have killed him? – I called Paolo Gentile on the number listed on Zarco’s mobile phone, but I wasn’t at all surprised when the call went straight to his voicemail. I left a message asking Gentile to call me urgently.

By now I had also realised just how sensitive all of these texts were and how dearly the police would have wanted to see what was on Zarco’s phone. Of course I knew that I was committing a serious offence by not handing it over – withholding evidence in a murder inquiry carries a prison sentence, and I knew all about what that was like. I had no wish ever to go back to Wandsworth. But Zarco’s reputation and that of London City were of greater consequence than this. For the first time in my life I knew the absolute truth of Bill Shankly’s famous quote when he was still the manager of Liverpool: ‘Some people believe football is a matter of life and death… I can assure you it is much, much more important than that.’

And how.

I went along to the players’ lounge where everyone was watching Sky Sports, just for a change – Tottenham versus West Bromwich Albion, the first of three Super Sunday televised matches. In the studio before the match there was, of course, plenty of talk about Zarco’s death and my appointment as manager, which the three pundits seemed to think was a good thing. I tried not to pay attention to it but I’d always respected Gary Neville; that back pass to Paul Robinson in the Euro 2008 qualifier against Croatia aside, you had to admire a man who, at the age of just twenty-three, had had the strength of character to tell Glenn Hoddle just what he thought about the faith healer the England manager had brought into the squad.

Every so often an attractive uniformed WPC with a clipboard from the Essex Constabulary would summon one of the players or staff who’d been at Silvertown Dock the day before for a short interview with a detective; but this seemed to be taking a while and some of the lads near the end of the alphabet were impatient to get back home to spend what would have been a rare Sunday with their families. A few of the others were behaving in a rather boorish and tiresome way towards the poor WPC; when she came into the room one of the younger players said, ‘Hey, lads, the stripper’s here,’ and I quickly gained the impression that this had been going on for a while.

‘That’s enough of that,’ I said firmly. ‘This woman has got a job to do. Try to remember that this is a murder inquiry and treat her with respect.’

Which was good, coming from me.

Everyone groaned, not because they disagreed with me but because Tottenham, who were just three points behind us in the table, scored first.

‘Hey, boss, can you get someone to turn the heating on? It’s brass monkeys in here,’ someone said. ‘We’ve asked Big Simon but nothing seems to happen.’

Which explained why a moody-looking Ayrton Taylor was wearing a black shearling coat from Dolce & Gabbana which seemed to match his curly, rockabilly hair; on the other hand, since the coat cost seven grand, maybe he just didn’t want to leave it lying around for someone to fuck with – give it a haircut, perhaps. I couldn’t blame him for that. Players were always pissing around with each other’s clothes – cutting the arse out of a pair of jeans, and sometimes far worse. I’d looked at that coat in the shop myself and decided that a) seven grand was far too much to pay for a coat and b) I looked like a tit in it anyway. That was how Sonja came to buy me a nice grey cashmere coat from Zegna. Taylor’s hand was still bandaged but he wasn’t trying to hide it in his pocket as perhaps he might have done if he really had battered Zarco to death.