Jane Vejjajiva (4 page)

Authors: Unknown

It was only Mother’s voice that Kati could remember well.

The shrine room, with its tiers of gold-lacquered tables, was another place Grandma spent a lot of time each day. On the table rested the image of the Buddha.

Kati picked jasmine blossoms and threaded them onto thin stalks of bamboo to place in the altar vases. When she’d had her bath and was nice and clean, Kati would take the vases in to Grandma. The shrine room always seemed cool and pleasant. Grandma said it was a blessing from the holy images whose merciful protection extended to everyone in the house. Grandpa muttered that actually it was because the shrine room was on the north side of the house and got all the wind and none of the sun.

Before the shrine was a large urn for incense sticks. Grandma liked to light incense sticks in offering to the Buddha. Kati didn’t like the heady aroma of the incense and the smoke stung her eyes and throat. But she liked to see the flames of the candles, burning steadily under their glass shades. Kati would look into the flame for long periods while Grandma was saying her prayers. Line by line, verse by verse, her prayers seemed to go on forever. Grandpa said that if Grandma collected bonus points for all her prayers, there should be enough for a ‘frequent flyers’ ticket to heaven for him too. He’d laughed, enjoying his own joke, but Grandma had been cross with him for days afterwards.

The incense urn was filled to the brim with

fine white sand. Kati couldn’t imagine

where Grandma had found such

white sand; there was certainly

none nearby as the sand round here

was coarse and brown. Kati liked the

sensation of pressing the incense

sticks into the smooth surface

of the sand. Once in a long

while, the urn had to be taken

outside and emptied, and the sand changed. Kati could lift the urn but couldn’t manage to carry it down the stairs. Grandma didn’t risk carrying it herself either; this was a task she found someone to help her with. Sometimes Tong helped. He would also help Grandma pour libations on the Buddha statue, wipe clean the platform that held the Buddha, and generally dust and polish every part of the shrine. Usually this spring cleaning was carried out just before the Songkran water festival.

Wash, clean and get rid of all the grime that had accumulated over the year, to start afresh, with good fortune, said Grandma.

If people’s hearts were like the white sand in the urn that could be emptied and refilled again, all clean and white, how good that would be.

Kati started from her reverie when Grandma, having knelt and touched her forehead to the ground in homage to the Buddha, turned and looked at Kati. Kati would never forget that picture no matter how much time should pass, the picture of Grandma looking at her, and the sound of Grandma’s voice that accompanied the picture.

‘Kati, my dear, do you want to go see your mummy?’

e

by the sea

It had been many years since Kati had seen Mother.

Red sprays of peacock flowers rushed by on either side and the car sped forward as if it were flying. Kati felt light and insubstantial like an empty box. For the past two days her heart had pounded with excitement. It was as though the events that followed Grandma’s question had happened to someone else, as though Kati could see herself moving and speaking from the outside. She saw Grandpa walk into the room. He pulled Kati to him and hugged her tightly. He spoke slowly when he told her that Mother was ill, very ill. She had been to many places for treatment but could not get better.

Mother’s friend Aunt Da had come to pick up Kati and Grandpa and Grandma. Grandpa had let Kati decide for herself whether she wanted to see Mother or not. Grandpa shook his head when he said that, so far, everyone had made decisions for her, but this time it was up to Kati. They left early in the morning. In the car the air was very cool while outside the sunshine grew fiercer with every passing minute. Aunt Da drove with the practised ease of one who knew the route well. She slowed the car effortlessly to pause at the tollgates, then accelerated smoothly into the elevated expressway which swung round to the right and left like a roller-coaster in a fun park. The expressway ran between clustered skyscrapers and advertising billboards replaced the views of the countryside. It had seemed only a few seconds later that the car descended to the freeway which led away from the city. Kati’s attention wandered and she fell asleep, waking to see the red flames of the peacock flowers.

The car headed south. On the left were the sea and the beach; to the right a range of mountains could be seen in the distance. Grandpa and Grandma were talking in soft voices in the back seat. Aunt Da spoke on her mobile phone from time to time, and Kati could tell that there was only a short distance to go before she would see her mother.

Grandpa called peacock flowers ‘flame of the forest’. Kati had only recently learnt their real name. The Thai species had flowers of many colours – yellow, pink and red, not just the orangey-red she saw now. Kati liked the way the peacock flower trees were planted in an orderly row along the road. Grandpa said there used to be a lot more of them before they built the airport and cut them all down. When Aunt Da noticed Kati craning her neck to see the trees, she pulled over at a wayside shelter. Grandpa was happy to have the chance to stretch his legs and Grandma brought along her basket of snacks. The trees seemed different to the ones Kati had left at home. There was an unfamiliar tang in the air too, and Kati guessed it must be the salty smell of the sea.

The mobile telephone rang again. Although the ringtone was soft, they all started. Aunt Da said gently into the phone that they would be there very soon. It was the first time Kati had ever seen Grandpa holding Grandma’s hand. Grandma was gripping her basket so tightly with her other hand that her knuckles were white. The tips of Aunt Da’s fingers were icy-cold where they touched Kati’s warm palm. Kati bent and picked up some of the little sprays of peacock flowers from where they lay on the ground nearby. They still had their pretty red-orange petals. She took them to give to Mother.

The car stopped in front of a small house that looked clean and white with its contrasting window frames of bright blue. No one needed to tell Kati what to do; she opened the car door and let her heart lead the way.

Mother kissed Kati over and over again. Her long soft hair smelled sweet and refreshing. Mother’s voice, though hoarser than in Kati’s memory, was no less loving.

‘Hug Mummy tight, Kati, my darling child.’

It made no difference that it was Kati hugging Mother, not Mother hugging Kati. Their tears of happiness flowed and mingled together. Kati’s arms folded around her mother just as she had dreamt. Her embrace spoke the words of love she could not utter: that she loved Mother with all her heart, that she understood why they had to be apart, that she had missed her so. Kati did not know how long it was before she let go of her mother.

The peacock flowers were in a glass vase by the side of the bed already.

No one knew how much time Mother had left.

Kati had always thought that a beach would be made up of smooth, fine, soft sand stretching off into the distance. Only when she saw it for herself did she realise there was more to a beach than that. From the verandah of the house you could see the little pools of water the sea had forgotten and left behind the night before. A horse had left a long trail of hoof prints on the sand, right at the water’s edge. The person leading the horse had left footprints too. Grandpa said it was a good thing that the horse hadn’t left them a souvenir of a more substantial kind. He said nowadays people tending horses were armed with plastic bags so they could pick up the smelly dung and put it in the bins the council had provided at intervals along the beach.

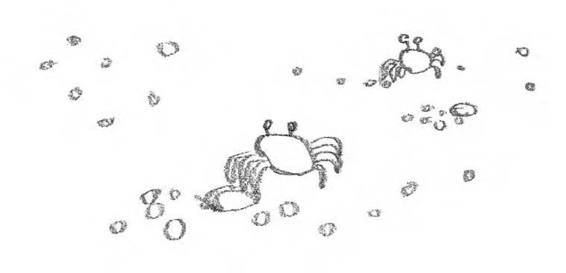

On the sand there were other strange markings. Kati sat and studied these at length. It was as if someone had rolled grains of sand into little balls and scattered them on the ground in a strange dotty pattern. Mother’s friend, Uncle Kunn, said it was the work of wind crabs. As they dug their holes they threw out the sand shaped into little balls by their claws. There must have been lots of crabs living on the beach, but Kati had yet to see if they lived up to their name and ran as fast as the wind.

Uncle Kunn did not speak much, but it was as if he had told Kati about all sorts of things and knew what she was thinking too. Sometimes they walked in silence along the beach in the evening. When they were tired they looked for a place to rest, and often sat together on the seawalls of shuttered-up beach houses.

From Uncle Kunn Kati heard all about this disease with many names. Americans called it ALS. The English called it MND or motor neurone disease. The French called it

Maladie de Charcot

(after the doctor who first identified the condition 150 years ago). Uncle Kunn spoke of Lou Gehrig, the American baseball player who’d had this disease and was the first to make its symptoms known to the general public. He went on to explain that there was no cure for the disease. Those with the condition suffered from progressive muscle weakening. They also lost control of their muscles. They couldn’t control the movements of their hands and arms. They found it difficult to walk, to speak, to swallow and eventually to breathe. The result, ultimately, was total paralysis.

Kati heard about the spirometer, the BiPAP machine and many other things that floated past her ears and disappeared with the sea breeze. Aunt Da said Uncle Kunn was a dab hand at writing scripts for radio advertisements. It must have been true because when Uncle Kunn explained to Kati, who was nine years old, about Mother’s illness, complicated things became simple.

The figures Uncle Kunn mentioned were easy to understand. Males got it more than females. Mostly people who had it were between forty and seventy. Fifty per cent of people died within eighteen months of diagnosis. Twenty per cent lasted five years. Only ten per cent of people lived longer than ten years. People who became symptomatic between the ages of twenty to forty usually lived more than five years.

Kati wondered whether, if the statistics had been different, she would feel as she did now. Mother first developed symptoms when she was thirty-three. She had been ill for nearly five years now.

The wind crabs scuttled down their holes before her eyes. Uncle Kunn asked casually if Kati would like to run a race with him, if he let her start from the pine tree in front of them and whoever made it to the hotel first would win. Kati didn’t wait to be asked a second time. She set off running.

The wind, mingled with the hot air rising from the sand, blew in her face. Kati ran faster and faster. She was running to the horizon. Her feet felt the fine sand beneath them in a way that Mother was no longer able to do… in a way that Mother had once done. Kati’s hands were clenched and they pumped up and down in rhythm. Her hands were moving in a way that Mother’s could no longer move. Kati raised her hand to wipe away her tears. That easy movement was something Mother could no longer do, though Mother had once done so just as easily as Kati.

The hotel entrance flashed by out of the side of Kati’s eye but she couldn’t stop. She raced on and prayed that the beach would continue before her, an endless beach. It was only when her knees gave way and she fell onto the sand that Kati realised she was soaked in sweat. Her legs were trembling. Kati cried without shame, as though all her defences had been shattered, as she had never cried before. Someone threw themself down beside her and swept Kati up in a hug. It was a good while before Uncle Kunn spoke. He said that her crying would flood the wind crabs’ holes. Kati laughed through her tears. Uncle Kunn shifted and gestured for Kati to hop onto his back. The view to either side looked different from up on high. Uncle Kunn laughed when he said that she’d probably not been thinking of how they would get back home when she’d run so hard and long.

The sky was dark now. Light shone from the verandah of ‘Sea-view Villa’. The tide was high so the beach had shrunk, and on the sand no trace remained of the wind crabs.