Jane and the Barque of Frailty (33 page)

Read Jane and the Barque of Frailty Online

Authors: Stephanie Barron

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Women Sleuths

There was a silence, as all those collected in the anteroom weighed Malverley’s words. It was possible that the wretched creature, disabused of every cherished notion of her lover’s worth and fidelity—the door slammed in her face—had indeed done herself a violence. I had an idea of her shivering in the cold of an April dawn, and of the desertion and essential bleakness of the square in that hour; the sharp fragments of porcelain gleaming whitely at her feet. Such a little thing, to reach down and seize the agent of her death—the agent of her peace, at last …

The remaining drapery was thrust aside, and William Skroggs stepped forward. “Mr. Charles Malverley, it is my duty to carry you before Sir Nathaniel Conant, of the Bow Street Magistracy, on suspicion of the murder of Princess Evgenia Tscholikova … ”

Chapter 31

End of the Season

Wednesday, 29 May 1811

∼

A

ND SO

I

AM ESTABLISHED COMFORTABLY ONCE

more in the sitting room at Chawton, where I may write my nonsense in peace at the Pembroke table, alerted to every advancing busybody by the squeak of the door-hinges. The countryside is in full bloom, the air is sweet, the considerations of each person in this village of so modest a nature, as to prevent the Kingdom’s survival from hanging upon them—tho’ equally consuming to the principals, as the Regent’s latest flirt must be to Him. I cannot regret anything I have left behind in London but the excellent society of Henry and Eliza, and the book room at Sloane Street, where I enjoyed so many hours in perusing Mr. Egerton’s typeset pages; even Mr. Chizzlewit is not entirely absent from my days, having adopted the habit of correspondence—in the guise of a respectful solicitor, regarding the affairs of a Lady Authoress. It was necessary to let him into the secret of Sense and Sensibility, as I foresee a time when I might require a smart young fellow’s offices in the matters of copyright, and payment.

I have received a missive from Mr. Chizzlewit’s chambers only this morning, in a packet of letters from London and Kent; Cassandra, who remains in the bosom of Edward’s family, having sent the news of that country—and Eliza offering a full two pages, crossed, of gossip concerning our mutual acquaintance in Hans Town. The Tilsons have determined to become advocates of the Evangelical reform of our Church of England, and have left off serving even ratafia at their suppers; Lord Moira is deeper than ever in debt, but betrays not the slightest knowledge of having mistaken Eliza for a Woman of the Town; Miss East has decided to write a novel of her own; and the d’Entraigueses are, for the moment at least, reconciled—the Comtesse having lost a fortune in jewels she might have sold, and the Comte his Julia Radcliffe.

That lady, contrary to expectation, did not capitalise on the ardent feelings of Julien d’Entraigues, by accepting his hand in marriage. She has chosen instead to continue much in the way she had begun: with independence, and strength of mind, and the lease of a cottage in Gloucestershire, where she might supervise the rearing and education of her son. The ruin of Charles Malverley having been achieved through no exertion of her own, she wisely determined that she need no longer make a display of her name and person—and has retired to a pleasant and comfortable obscurity. The comet of Julia Radcliffe, tho’ it blazed across London’s firmament for only a season, shall linger long in the memory of most of the ton; and such fame has been enough for her.

Of Charles Malverley himself there is little enough to say. He maintained his innocence in the death of Princess Tscholikova to the last; but it being represented to him, by so pointed an intelligencer as Bill Skroggs, that his perfidy towards Lord Castlereagh, and the suspicion of his having betrayed his government to the French Monster, were so thoroughly and generally understood in government circles, that he could never hope to be noticed by the ton again—that the unfortunate young man shot himself while yet awaiting the Assizes. It is thought that his father conveyed the pistol to Malverley in his gaol—the Earl of Tanborough being concerned, first and foremost, with the appearance of a gentleman in all respects.

Malverley’s death served to confirm the suspicions generally held, of his conduct towards the Princess—and cleared Lord Castlereagh of all scandal, without a word of denial having to be spoken by that gentleman. Lord Castlereagh’s name is still broached as a possible member of government— and Lord Moira’s with him; but of George Canning, I hear nothing.

Henry tells me that Egerton hopes to produce my darling child—Sense and Sensibility—by the end of October at the latest, and that I am to submit Pride and Prejudice for his consideration. I am resolved to commence work, therefore, on an entirely new novel—a story of innocence enshrined in the heart of dissipation and debauchery; of a heroine invested with sound Evangelical principles, that shall put shame to the Fanny Tilsons of this world; of a charming young man thoroughly given over to vice, and the frivolous world of the ton that smiles upon him. I should call it A History of Julia Radcliffe, as Told by a Lady—but must settle for something less particular. Perhaps … Mansfield Park?

Editor’s Afterword

S

ENSE AND

S

ENSIBILITY WAS FIRST ADVERTISED BY ITS

publisher on October 31, 1811, and similar advertisements appeared for several weeks following. It was a modest success that was capped by general admiration and clamor for Pride and Prejudice, when that novel appeared in 1813; and although Jane Austen was not then revealed as the author, subsequent novels were promoted as having been “by the author of Sense and Sensibility, and Pride and Prejudice.” Jane’s career and reputation were in a fair way to being made—and have endured for all time.

Readers of this detective amusement may be interested to learn the fates of some of its characters. Emmanuel, Comte d’Entraigues, and his wife, Anne de St.-Huberti, were murdered at their home in Barnes, Surrey, on July 22, 1812. They were discovered in bed with their throats slit; and a household servant was charged with the crime. When the news of this horror reached Jane, she must have experienced a certain sense of what we would call closure. D’Entraigues’s biographer suggests that during his lifetime he was employed as a spy against England by several governments, Russia and France being among them; but he was also certainly employed by George Canning, to provide intelligence to England of those nations’ intentions. The confusion of motives, policy, and fact that Lord Harold Trowbridge described in his 1808 journal, while analyzing the turf battles between Castlereagh and Canning, probably resulted from the deliberate design of Canning’s chief spy—Comte d’Entraigues. Which of the governments and patrons d’Entraigues regarded as meriting his true allegiance—if he was capable of any—is difficult to know; but he certainly promoted distrust between Russia and Great Britain. Those who wish to know more of his life may consult Léonce Pingaud, Un agent secret sous la Révolution et l’Empire: Le Comte d’Antraigues (sic) (Paris, 1894).

Julien, Comte d’Entraigues, lived out his life in London in a home in Montague Place, Russell Square, dying in 1861.

Spencer Perceval, who led the government during Jane’s visit to London, was assassinated in Parliament May 11, 1812. The Regent asked the Tory Lord Liverpool to form a new cabinet, and Lord Castlereagh to serve as foreign secretary—a post he held until his death. George Canning, who had wished to be named to that portfolio, was given nothing in 1812; Lord Moira was named governor-general of Bengal, where he lived for nine years. In 1817 he was made Marquis of Hastings.

Lord Castlereagh’s later career was not untouched by scandal. In 1822, having acceded to his father’s estates and title as Marquis of Londonderry, he began to receive blackmailing letters accusing him of homosexuality. Apparently, as Castlereagh told the story, he had been seen entering a brothel with a prostitute he later learned was a transvestite male. Whatever the truth of the situation, by mid-August of that year, Castlereagh was subject to a severe mental collapse and depression; he confessed his “crimes” to both the Prince Regent and the Duke of Wellington—two of his closest friends—and despite being under the watchful guard of his medical doctor, slit his throat with a razor.

The chief biographer of both Canning and Castlereagh is Wendy Hinde, whose workmanlike studies of the celebrated Regency statesmen, George Canning (London: William Collins Sons, 1973) and Castlereagh (London: William Collins Sons, 1981) are well worth reading.

Stephanie Barron

Golden, Colorado

September 2005

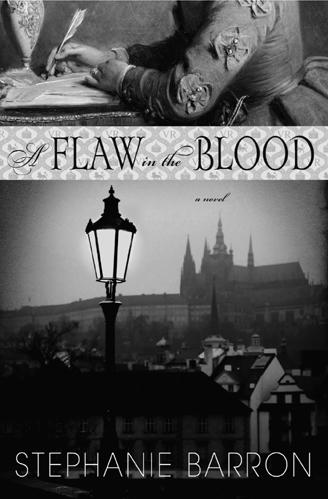

A Flaw in the Blood

by Stephanie Barron

Coming soon from Bantam

If you enjoyed Stephanie Barron’s

Jane and the Barque of Frailty

, you will want to read all of her bestselling Jane Austen novels, as well as all of the thrillers she writes as Francine Mathews. Look for them at your favorite bookseller.

And read on for an exciting early look at Stephanie Barron’s newest historical novel,

A Flaw in the Blood

COMING SOON

Chapter One

The carriage made little sound as it rolled beneath the iron portcullis of Windsor; the harness and wheels were wrapped in flannel, the paving stones three inches deep in sawdust. But its arrival fell upon the place like an armed attack, shaking the ostlers out of their torpor. They sprang to the horses’ heads before the equipage had even pulled to a halt, as though Patrick Fitzgerald brought tidings of war.

Fitzgerald made no move to step down into the sawdust. His hands were thrust in his coat pockets for warmth, his eyes fixed on the flaming torches and silent men beyond the carriage window. Once before, he had been to the great stone pile west of London— summoned, as tonight, by the woman who ruled there. But he was thinking less of the Queen now than of the man who lay in her private apartments, shuddering with fever.

“Let me come with you.” Georgiana’s gloved hand—that supple hand, so deft with the knife blade—reached for him. “I want to come with you.”

“No.”

Darkness filled the carriage. Only the gleam of her eyes suggested a presence; she had drawn the hood of her cloak close about her face, like a thief.

“It may have nothing to do with you, Georgiana. You cannot always presume—”

“And what if I have something to do with it?” she interrupted. “With him?”

“Georgie—”

But she’d turned her head away, her profile outlined against the squabs. She was biting down hard on her anger, as though it were a haft of iron between her teeth.

“And she’d never let you near him,” he attempted. “You must know that.”

“Then she’s a fool!”

The coachman stumbled as he jumped from the box; the noise reverberated against the chilled stone like a gunshot, and the ostlers stared in outrage. Silence in the Old (Quadrangle, in respect of the dying. Fitzgerald caught the coachman’s indrawn hiss of breath, ripe with fear, as he pulled open the door.

“Wait,” he told Georgiana. “I shan’t be long.”

She didn’t attempt to argue. She would be freezing soon, he thought, despite her layers of petticoats. But Georgie would never ask for a hot brick, a brazier of coals. Her pride would kill her one day.

A footman led him into Windsor by the lower entrance, and there, too, the stone floor was blanketed with sawdust. The castle was known for its menacing silence—the vast, carpeted halls absorbed every footfall, and its people trafficked in whispers. Fitzgerald neither spoke nor offered his hand to the man who awaited him—William Jenner, court physician and eminent man of science.

“You took your time,” the doctor snapped.

Fitzgerald handed his gloves and hat to the footman before replying. “I was in Dublin but two days since.”

“And you stink to high heaven of strong spirits.”

“Would you have had me miss my dinner, then? I only received your summons at five o’clock.”

“It is nearly ten! As I say—you took your time.” Jenner’s eyes were small and close-set, his jowls turned down in perpetual disappointment. He surveyed the Irishman’s careless dress, his unkempt hair, with disfavour. “It may be that she will not receive you, now.”

“I didn’t ask for the audience.” Fitzgerald shrugged indifferently. “Is it so necessary?”

“I would not thwart her smallest wish at such an hour! I fear too much for her reason.”

“And your patient? How is he?”

“Typhoid.”

Jenner had made his reputation, years ago, by distinguishing typhoid fever from its close relative, typhus. The physician was the acknowledged expert in the thing that was now killing Prince Albert.