Jacko, His Rise and Fall: The Social and Sexual History of Michael Jackson (36 page)

Read Jacko, His Rise and Fall: The Social and Sexual History of Michael Jackson Online

Authors: Darwin Porter

"I always remember the song you sang," Michael said, obviously in awe.

"You're All the World to Me," Astaire said. "I remember it well."

Long after he gave up dancing in public, Astaire still put on private shows,

as he did one night for Michael. He sat at his drums and pounded out some

rhythms, before getting up and performing a few dance steps for Michael.

"Better watch out!" Michael warned. "I'll steal those steps from you too."

"Feel free," Astaire said. "At my age, I'm glad to be walking."

Michael confessed that he used to sit in front of his television, using his

video cassette's stop-and-rewind switches to dissect every dance step his mentor made.

"I stole that idea of going up on my toes from those classic movies you

made back in the 30s," Michael told Astaire.

"Those were the days," Astaire said with a touch of nostalgia.

"Anybody who can sing and dance at the same time-and do both wellis pretty darned good," Astaire said. "And that's what Michael does."

Michael would later be nominated for an Emmy Award in the musical category. Even though he lost to Leontyne Price, he felt Astaire's compliment

took away some of the sting of defeat.

When Michael's so-called autobiography, Moonwalk, was published, he

dedicated it to Fred Astaire.

After Astaire's death in 1987, and when Michael was preparing his 1988

Moonwalker, a full-length feature film, he received a major disappointment.

Michael choreographed a dance sequence in which he'd superimpose himself

onto one of Astaire's films, becoming in essence the dancer's Ginger Rogers.

It was a brilliant idea and would have made for a first-rate film memory. But

the female jockey who Astaire married at the end of his life, Robyn Smith,

refused to give Michael permission to use the footage.

When Sarah Giles composed her collection of remembrances about

Astaire, she asked Michael to contribute. In Fred Astaire. His Friends Talk,

Michael wrote: "I could only repeat what has been said and written about Fred

Astaire's perfectionism and enormous, one-of-a-kind artistry. What I can

reflect on is the inspiration he afforded me personally, being privileged as I

was to see him work his magic. Nobody could duplicate Mr. Astaire's ability,

but what I never stop trying to emulate is his total discipline, his absolute dedication to every aspect of his art. He rehearsed, rehearsed, and rehearsed some

more, until he got it just the way he wanted it. It was Fred Astaire's work ethic

that few people ever discussed and even fewer could ever hope to equal."

In the 1980s, many critics and writers called Michael the Fred Astaire of

his era. Such a tribute was expressed by Sandy Duncan in People Extra: "Fred

Astaire was to that era and that music, the way the music moved through him

in the 30s, what Michael Jackson is to this era. You could put him behind a

scrim and see his silhouette and you'd know who he was. It's like he's got a

direct connection to God, because those moves just come from within him and through the music."

In the wake of Astaire's approval, Michael's

other idol, Gene Kelly, also paid him a visit at

Encino. Michael estimated that he must have

watched Kelly dance with the cartoon figures, Tom

& Jerry, at least a hundred times in the 1945 film,

Anchors Aweigh.

Gene Kelly

In time Kelly would return the compliment,

filming a taped tribute to Michael for his self-serving lovefest broadcast on Showtime cable TV.

Kelly enthralled Michael with his insider show business stories, admitting, "I wasn't nice to Debbie-it's a wonder she still speaks to me." He was

referring to working with Debbie Reynolds on the 1952 Singin'in the Rain.

Michael told Kelly that he thought this was the greatest movie musical of all

time.

He warned Michael that if he ever became a musical star in films, he

should get used to being overlooked by The Academy. "It's a form of snobbism," Kelly said. "Members feel that drama is more deserving of awards than

comedy."

Michael complimented Kelly on his all-ballet film, Invitation to the

Dance. "I was never allowed to complete the picture," Kelly said. "The plug

was pulled on me. The version released in 1956 was never finished. I was furious. Of course, I got disastrous notices. I took to bed for three weeks."

He blamed the director, Vincente Minnelli, for the disappointing

Brigadoon, released in 1954. "You see, Vincente was in love with me .. .

always was. When you're in love, you can't be objective as a director."

Kelly expressed his regret at his treatment of Judy Garland during the

shooting of The Pirate in 1948. "She and Vincente were breaking up, and she

was on the verge of a nervous breakdown and the beginning of a long and protracted illness," Kelly said. "Vincente didn't help matters by spending all his

time in my dressing room panting after me like a puppy dog."

Michael appeared shocked at these revelations.

Kelly warned Michael, "Don't get carried away with your own brilliance

in the studio. Both Vincente and I thought The Pirate was going to be the

greatest musical of all time. At least we thought that for forty-eight hours.

Perhaps only six people in America understood where we were going. In fact,

Vincente kissed and licked my toes in gratitude for the performance I gave."

Before departing, Kelly told Michael: "So many men-women, toohave fallen for me. Judy herself, Peter Lawford. Noel Coward. Every chorus

boy I've ever danced with developed a crush on me. As a lover, I never

returned love. An artist can only love himself, and I'm sure you agree."

"How do you cope with all those gay rumors," Michael said. "They say

bad things about me. That I'm a homosexual, and I'm not! How do you

answer such questions?"

"Enigmatically," Kelly responded. "I tell my inquisitors that I'm not gay.

Merely an Irish leprechaun. There's a difference you know."

At the door, Kelly gave Michael a warm embrace and a theatrical kiss.

"You're going to be king in the 80s. For Fred and me, there's not much left

except accepting lifetime achievement awards."

"Can you believe it?" Michael endlessly asked of anyone even remotely

concerned. "The great Fred Astaire, the great Gene Kelly told me that I was

just as great a dancer as they were in their prime. What can any future award

mean to me when I get praise like that?"

Astaire and Kelly might approve of Michael, but not the members of his

church, The Jehovah's Witnesses.

Michael might have tried to appease members of Jehovah's Witnesses and

distance himself from Thriller, but he wasn't going to let the fanatical religious sect deter "me from the greatest night of my life." He showed up at the

1984 Grammy Awards to receive all those accolades for Thriller, and it would

mark the pinnacle of his career. It would also turn into one of his most infamous appearances, launching him on the long road toward a forever tarnished

reputation.

When Michael walked into the auditorium to receive his Grammys, he

had child star Emmanuel Lewis on his left and the beautiful Brooke Shields

on his right. The trio was, in the words of Walter Yetnikoff, "a menage a trois

to make the Marquis de Sade blush."

"I didn't get destroyed by the press and fan mania and neither will Michael. He's very talented. He knows how to make

records that people like. But he's a very straightforward kid.

He has a great deal of faith. He's got a great deal of innocence

and he protects that especially. Michael looks at cartoons all

day and keeps away from drugs. That's how he maintains his

innocence. "

--Paul McCartney

"I did it as a favor. I didn't want nothing. Maybe Michael will

give me dance lessons some day. I was a complete fool,

according to the rest of the band and our manager and everybody else. "

--Eddie Van Halen, on playing 'Beat It' for free

"No dope-oriented album ever sold as much as Thriller, and

no vulgar artist ever became so famous as Michael has. "

--The Rev. Jesse Jackson

"Thank God for Elizabeth Taylor. She protected me."

--Michael Jackson

"He wasn't ever really interested in money. I'd give him his

share of the night's earnings and the next day he'd buy ice

cream or candy for all the kids in the neighborhood. "

--Papa Joe Jackson

"My Lord, he's a wonderful mover. He makes these moves up

himself and it's just great to watch. Michael is a dedicated

artist. He dreams and thinks of it all the time. "

--Fred Astaire

The Grammy Awards in 1984 alerted keen observers to Michael's interest

in young boys. In his future, these boys-with an occasional exceptionwould be white. Not so Emmanuel Lewis, an African-American who was born

in Brooklyn in 1971, which made him thirteen years old when Michael took

him and Brooke Shields as his "dates" to the Grammys.

Michael met the pint-sized actor-known at the time as "The Tallest 40

Inches in Hollywood"-at an awards ceremony. They became intense friends,

a relationship that would last for many years. It was another odd coupling for

Michael. Lewis was rumored to be a midget,

but endocrinologists claimed he had all the

potential for normal growth.

Speculation about the relationship became

rampant when Michael and Lewis appeared in

public dressed alike. They spent many happy

hours even days-together. When Lewis

went somewhere with Michael, he was often

mistaken for Gary Coleman, the Diff'rent

Strokes TV child star. Both of these performers are short, African-American in origin, and

had starred in sitcoms about trans-racial adoptions.

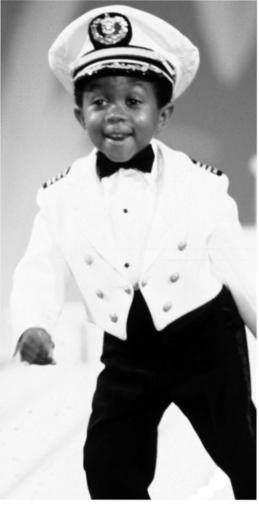

Emmanuel Lewis

Lewis was twelve years old when his sitcom, Webster, premiered in 1983. The series

finale would come just one day after his 18th

birthday. Michael was a faithful fan of the

series.

Before hitting it big on Webster, Lewis

had starred in TV commercials, hawking fruit juice, glue, soup, toys, stereos, coffee, puddings, pizzas, and Burger King. He

told reporters, "Though I'm still little, my heart and dreams are as big as ever."

It was during the making of those TV commercials that Michael became

"smitten" (La Toya's words) with Lewis. Brazenly, Michael called the talent

agent, Margaret Lewis, the young actor's mother, and asked her permission to

allow her son to spend time at Hayvenhurst. Not suspicious at the time, she

seemed delighted that a big star like Michael had expressed an interest in her

son.

It was all fun and games, as they wrestled on the lawn at Encino, played

cowboys and Indians, or petted the animals, including the boa constrictor,

"Muscles," in Michael's zoo. Michael claimed that although boa constrictors

could not devour the average person whole, Lewis was "just the right size for

a tasty snack." In response, the child actor would run screaming into the

house. Much time was spent in Michael's darkened bedroom watching

movies. Sleepovers-later to become a notorious fixture in Michael's lifefollowed.

Steve Howell, who became Michael's unofficial videographer, captured

on film many intimate moments between Lewis and Michael. "Yes, hugging

and the most intimate cuddling," Howell was quoted as saying. "It's all on

home video."

In March of 2005, In Touch Weekly, a tabloid, shocked Michael's fans by

publishing a photograph of him, along with Lewis, lying in bed sucking on the

nipples of baby bottles. "How retro!" a fan wrote Michael. "How could you?

Talk about trying to relive your second childhood."

When he turned thirteen, Lewis received a diamond-and-gold "friendship" bracelet from Michael that allegedly cost $15,000. "It weighed more

than Emmanuel did," said a Jackson family member. This was a great exaggeration, of course, but at the time, Lewis weighed only forty pounds.

Michael was twenty-five years old

when he launched this strange friendship with a boy about half his age. Some

family members, including La Toya,

were often embarrassed by the whispering and giggling between the two, but

Michael refused to talk about Lewis and

asked that the Jacksons not probe into

his personal relationships.