It Takes a Village (15 page)

Read It Takes a Village Online

Authors: Hillary Rodham Clinton

When it comes to the dangers that pervade our homes and communities these days, we could take a cue from that sheriff. However fearful or uncertain we are, we have obligations to our children. Home canâand shouldâbe a bedrock for any child. Communities canâand shouldâprovide the eyes and enforcement to watch over them, formally and informally. And our government canâand shouldâcreate and uphold the laws that set standards of safety for us all.

It would be nice if there were a yellow brick road that would transport us magically to a place of absolute invulnerability. There's no place like that, and there never was. But there are many examples we can followâin our homes and beyond themâthat will lead us and our children toward the security we all deserve.

You have brains in your head.

You have feet in your shoes.

You can steer yourself

Any direction you choose.

DR

.

SEUSS

O

f the many extraordinary world figures I have met, Nelson Mandela is a standout, not only for his political leadership but for the moral authority he has provided, in word and deed, since his release from prison in 1990, after twenty-seven years. Having long admired him, I was deeply honored to attend his inauguration as President of South Africa with the American delegation headed by Vice President Gore.

The inauguration was an exuberant celebration of South Africa's passage from apartheid to democracy, but for me, the high point came after the official ceremony, at a luncheon President Mandela hosted at his new residence. Addressing a crowd that included representatives from almost every nation, some of whom were at war with one another or were major violators of the human rights of their own citizens, he spoke of his people's need for love, loyalty, and reconciliation. He also mentioned that he had invited three of his former jailers to attend the luncheon and the day's celebrations.

I was dumbfounded. How many of us, I wondered, would have had the character, self-confidence, and faith to extend forgiveness to those who subjected us and our loved ones to brutal persecution?

In October 1994, Bill and I had a chance to return the South African President's hospitality. At a state dinner in Mandela's honor, my husband toasted him, quoting from a letter Mandela had written to one of his daughters during his long imprisonment: “There are few misfortunes in this world you cannot turn into personal triumphs if you have the iron will and necessary skills.”

Â

O

NE OF THE

family'sâand the village'sâmost important tasks is to help children develop those habits of self-discipline and empathy that constitute what we call character. They enable us to be resilient in the face of the problems we encounter in life and to grow bigger, not bitter, in spirit.

Each of my parents had a different approach to character building. Both approaches were meant to give us the confidence to negotiate life's sharp edges without compromising our integrity. When difficult or challenging situations would arise, my mother always posed the same question to me: “Do you want to be the lead actor in your life, or a minor player who simply reacts to what others think you should say or do?” Asking myself that question has helped me through many difficult times.

My father's approach was vintage Hugh Rodham. When I was facing a problem, he would look me straight in the eyes and ask, “Hillary, how are you going to dig yourself out of this one?” His query always brought to mind a shovel. That image stayed with me, and over the course of my life I have reached for mental, emotional, and spiritual shovels of various sizes and shapesâeven a backhoe or two.

Children can learn early on to grasp those imaginary shovelsâor any tool that works for themâgaining from their parents and the other adults around them the essential skills of problem solving and coping with adversity that build character in daily life. Life itself is the curriculum, as are history, literature, current events, and, especially, religious teachings.

Nelson Mandela derived inspiration and guidance when he studied the actions and words of leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King. The lessons men and women have learned over thousands of years are available to anyone, in the form of fables, stories, poems, plays, proverbs, and scriptures that have stood the test of time. A wonderful new anthology of such writings is found in

A Call to Character,

edited by Colin Greer and Herbert Kohl.

You never know where you might find such guidance when you need it. One of Chelsea's and my favorite nursery rhymes summed up the absolute unpredictability and frequent unfairness of life: “As I was standing in the street / As quiet as could be / A great big ugly man came up / And tied his horse to me.” I thought often of that rhyme during our first year in the White House: My father died, our dear friend Vince Foster killed himself, my mother-in-law lost her battle against breast cancer, and my husband and I were attacked daily from all directions by people trying to score political points. To deal with my feelings I could turn to my religious beliefs, my husband and family, and my friends.

I also sought out and found new ways of thinking about my life and the challenges I faced. I read avidly about how my First Lady predecessors had played the hands dealt them during their turns in the spotlight. I reread favorite scriptures, quotations, and writings that had touched me in the past. I discovered new sources of support, inspiration, and clarity in books and people.

One of the people I encountered, through his writings and tapes, was the Reverend Henri Nouwen, a Jesuit priest and the author of meditations on his and our world's spiritual journey. His book

The Return of the Prodigal Son

analyzes that New Testament parable from the perspectives of the father and both his sonsâthe one who returns home after squandering his fortune and the dutiful older son who never left. One sentence hit me over the head likeâwell, like a shovel: “The discipline of gratitude is the explicit effort to acknowledge that all I am and have is given to me as a gift of love, a gift to be celebrated with joy.”

I had never thought of gratitude as a habit or discipline before, and I discovered that it was immensely helpful to do so. When I found myself in a difficult situation, I began to make a mental list of all that I was grateful forâbeing alive and healthy for another day, loving and being loved by family and friends, experiencing the awesome privilege of working on behalf of my country and its citizens. By consciously reminding myself of my blessings, I could move myself from pessimism to optimism, from grief to hopefulness.

From the beginning, Bill and I have tried to equip Chelsea with her own batch of shovels. We have tried to help her to develop her own spiritual life. We have also tried to anticipate the challenges she will face and to assist her in meeting them. One of our chief worries, naturally, has been how to protect her from the inevitable fallout of her father's public career.

In 1986, my husband ran for reelection as governor of Arkansas. During his previous campaigns, Chelsea had been young enough that we could monitor what she heard or saw about her father's political activities. But now she was six, and much more a part of the village in her own right. She went to school, she could read, and she was generally more aware of what was happening in the world outside our home.

When two combative former governors decided to run against Bill, we knew we had to brace ourselves for a messy campaign. We discussed the situation and decided to prepare Chelsea so she would not be surprised or overwhelmed if she heard someone say something nasty about her father. It is not a pleasant duty, teaching harsh truths to a child, but we wanted her to develop the skills she would need to cope with whatever life sent her way. And we wanted to teach them in a way that would promote her confidence in dealing with the world, rather than making her cynical about it.

One night at the dinner table, I told her, “You know, Daddy is going to run for governor again. If he wins, we would keep living in this house, and he would keep trying to help people. But first we have to have an election. And that means other people will try to convince voters to vote for them instead of for Daddy. One of the ways they may do this is by saying terrible things about him.”

Chelsea's eyes went wide, and she asked, “What do you mean?”

We explained that in election campaigns, people might even tell lies about her father in order to win, and we wanted her to be ready for that. Like most parents, we had taught her that it was wrong to lie, and she struggled with the idea, saying over and over, “Why would people do that?”

I didn't have a good answer for that one. (I still don't.) Instead, we asked her to pretend she was her dad and was making a speech about why people should vote for her.

She said something like, “I'm Bill Clinton. I've done a good job and I've helped a lot of people. Please vote for me.”

We praised her and explained that now her daddy was going to pretend to be one of the men running against him. So Bill said terrible things about himself, like how he was really mean to people and didn't try to help them.

Chelsea got tears in her eyes and said, “Why would anybody say things like that?”

Our role-playing helped Chelsea to experience, in the privacy of our home, the feelings of any person who sees someone she loves being personally attacked. As we continued the exercise during a few dinners, she gradually gained mastery over her emotions and some insight into the situations that might arise. She took turns playing her father and one of his opponents, former governor Orval Faubus. She worked on her speeches and asked questions. For example, when she learned that as governor, Faubus had been responsible for closing Central High School in Little Rock in 1958, she mentioned in one of her pretend speeches that he closed schools to keep black children out, while she (Bill Clinton) would never do that.

Bill and I have continued our dialogue about politics with Chelsea over the years, helping her to discern motives and develop perspective so that she can form her own judgments regarding what she sees and hears. Looking back, I am glad that we started to prepare her at a tender age, because by the time her father ran for President, we were even less in control of the messages to which she was exposed. Each time she went out into the world I ached, afraid of what or whom she might encounter. But I reminded myself that we had done the best we knew how to do under the circumstances. We had tried to give her the tools to deal with the hurt from which we could not shield her, and we had to hope that as a resilient young woman, she would know how to use them.

Before and after we moved into the White House, I had the good fortune and honor to spend time with Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. I admired the way she had raised her own children under extraordinary circumstances, and I was eager to hear her thoughts on the challenges that come with parenting when it feels like the whole world is watching.

She stressed the importance of giving children as normal a life as possible, of granting them the chance to fight their private battles while protecting them from public exposure. She told me how, when John was a little boy, he had once been harassed by a bully while riding his bike in a park. The Secret Service had stepped in to prevent an altercation. Jackie told them that the next time something like that happened, they should let John fend for himself. He needed to learn how to take care of himself, because there wouldn't always be a Secret Service agent or a concerned mother two steps behind him.

These may sound like the problems of privileged parents and children, and they are. But they are not so different in nature from the balancing act every parent must attempt: when to protect and when to stand back, when to hold on and when to let go. Much as we want to keep our children from harm, we won't always be there for them, and sometimes the most sympathetic thing we can do is to let them tough it out for themselves.

When my family moved to Park Ridge, I was four years old and eager to make new friends. Every time I walked out the door, with a bow in my hair and a hopeful look on my face, the neighborhood kids would torment me, pushing me, knocking me down, and teasing me until I burst into tears and ran back in the house, where I would stay for the rest of the day. Such was the fate of the new kid on the block. After this had gone on for several weeks, my mother met me one day as I ran in the door. She took me by the shoulders, told me there was no room for cowards in our house, and sent me back outside. I was shocked, and so were the neighborhood kids, who had not expected to see me so soon. When they challenged me again, I stood up for myself and finally won some friends. It was not until much later that my mother told me she had watched from behind the dining room drapes, shaking with worry, to see what would happen.

Now that I'm a mother myself, I know how hard it is to make decisions like that. My daughter would describe me as overprotective, although she generally indulges me and puts up with my worrying good-naturedly. Of course, there are places where Bill and I draw the line to protect her. We have actively shielded Chelsea from the press, for example, believing that children deserve their childhood and cannot have it in the public limelight. It isn't fair to let them be defined by the media before they have the chance to define themselves. We have taken some flak for this, but more than a few reporters have privately told us that we are doing the right thing.

When it comes to everyday life, however, parents have to concentrate on instilling self-discipline, self-control, and self-respect early on, and then must allow their children to practice those skills the way they would let them exercise their muscles or their brains. As my mother taught me, even very young children can be given a sense of strength in the face of indifference or cruelty. Part of that strength comes from experiencing appropriate discipline.

Â

T

HE NEED

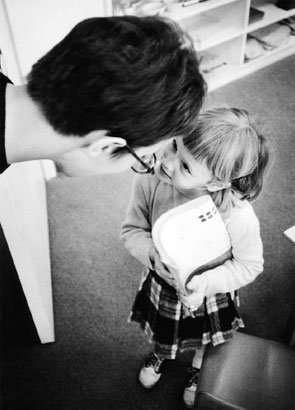

for discipline usually arises when children hit their “terrible twos.” This is the time when kids begin to test the limits of their powers, issuing endless edicts and vetoes in an effort to control the world around them.

Many parents find themselves unsettled by their new role, which seems to change overnight from all-powerful caregiver to cop. Young parents, in particular, may be frustrated by a toddler's newfound assertiveness and stubbornness. Frustration can quickly give way to anger, and worse. We have all seen a parent slap a child for a seemingly trivial infraction.