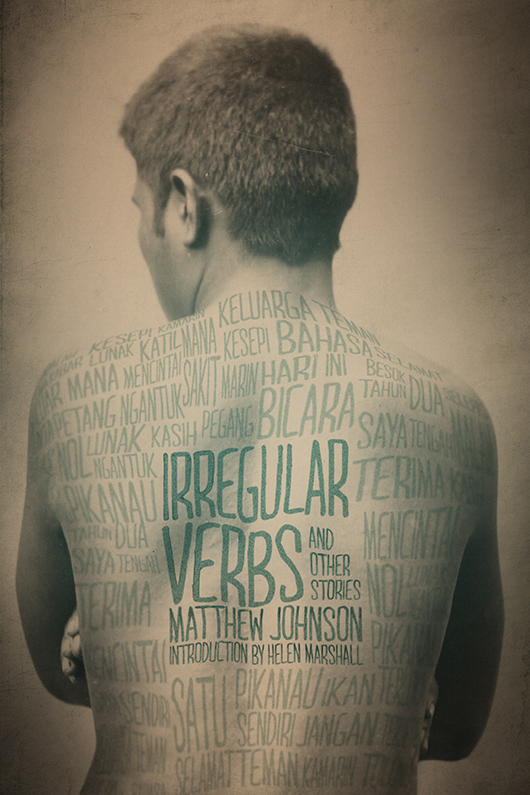

Irregular Verbs

Authors: Matthew Johnson

ChiZine Publications

EDICATION

This book is for Megan, of course

NTRODUCTION

| H

elen

M

arshall

Every writer dreams of a perfect language.

I met Matthew Johnson at a local convention in 2010. I remember that period of my life with surprising clarity: at the time, I was a graduate student at the Centre for Medieval Studies in Toronto, the type of scholar that Geoffrey Chaucer might have been describing in the

Canterbury Tales

if you updated the book by some six hundred years, the kid with horse rake-thin and robes threadbare who chose “some twenty books bound in black and red” as the appropriate destination of a university stipend rather than something as practical as a hot meal. Books on medieval siege weapons,

Beowulf

, Aristotelian philosophy, fourteenth-century feasts, Arthurian romances: in short, whole worlds of knowledge that were barely a hair’s breadth from the kind of fantasies I had had in my head since I cracked open the

Lord of the Rings

when I was twelve and which I was in the process of rediscovering.

A paradise? Of sorts. But even in paradise there was a shadow.

That shadow was my daily Latin tutorial, a deliberate torture imposed by the administration on all students in the program.

To become a doctor of medieval studies, you see, it was necessary to show mastery over the primary language of the Middle Ages through two brutal exams: the twin gauntlets every student in the department had to run. To prepare, we spent an hour every day for three years—an hour we all desperately

needed

for writing grants, marking essays, preparing conference papers and generally staying afloat in the unkind seas of academia—in a dimly lit office with five or six of our fellow classmates, staring at partially deciphered scribbles we’d made on the texts of John of Salisbury, Osbert of Clare or Petrarch. And all the while we waited—we waited in terror!—for the knotted and nicotine-stained finger of one Professor Rigg to point our way.

“Speak,” he would say. His voice was deceptively quiet, authoritative. He would lean back in his chair, an old man, you might think, close to eighty years old, bones that had survived countless Canadian winters, eyes that had looked on and judged practically every tenured professor we knew.

In that moment, I would dream of a perfect language. A language I could summon forth without pause, a language that would effortlessly reveal itself to me and to my colleagues. We all dreamed of this language. Every one of us.

And, one by one, we would open our mouths.

And, one by one, we should shut them. Driven to silence and shame.

Even though we had each studied the subjunctive, we had each separated our gerunds from our gerundives, and made ourselves

maestri

of the passive periphrastic, still, that ancient finger, that low, inscrutable voice obliterated thought.

Every writer dreams of a perfect language. Every writer dreams of a language that obeys, that comes to heel. For some this language is spare and pure, pared down to reveal essential truths without ornament or obfuscation. For others it is devilish and twisting, folding back over itself to create layers of meaning, shades of nuance.

A language that will survive through the ages.

A language that will crack open the hearts of readers like a hazelnut.

Enter Matthew Johnson and his

Irregular Verbs

.

Matthew Johnson never took Latin with me—though when I met him he was as equally conversant on the subject of science fiction as he was on Middle English poetry, a true polymath —but I wish he had: he would have been the quiet student at the back, boyishly good-looking, raised with a keen awareness of Canadian politeness and known for his wry sense of humour. The kind of person you might easily ignore at first glance.

And so perhaps Professor Rigg would have underestimated him, as the rest of us might have. Perhaps Professor Rigg would have pointed that gnarled tree-root of a finger at Matthew Johnson and commanded him to speak.

And, by George, would Professor Rigg have been in for a surprise!

Because here is a writer who can not only untangle the words of the ancients without a hitch—without a gulp!—but can

make something new

. Here is a writer who isn’t afraid to speak. And whatever language he chooses becomes a tool effortlessly wielded in the service of his narrative.

Matthew Johnson is one of the very best science fiction and fantasy writers that you’ve never heard of. Persuasive and insightful, globally aware, witty and wondrously intelligent. He has been praised by the some of the most respected reviewers and editors working in the field, and this debut collection, which gathers together his finest stories, shows that praise is well-earned. Johnson’s stories cajole and whisper, they dazzle and delight, but above all they show a complete mastery of the language of genre fiction—not through heavy-handed purple prose but through simple, elegant, evocative language. Language that makes you feel.

Let me start with an example that Professor Rigg might have enjoyed.

In one of the gems of the collection, “Another Country,” Romanized Goths fleeing from Attila the Hun’s invasion become refugees (or prefugees as they are cleverly designated) in a future where refugees from the Mongol invasions end up in Seattle, Aztecs in Paris, and Romans in Ottawa. They speak to each other in perfect Latin—“Te salute do, amici,” Galfridus officially welcomes the new arrivals—and what follows is a flawless story of culture shock and dislocation that demonstrates Johnson’s meticulous attention to detail in creating worlds that can only be described as

authentic

.

Understand: what makes Johnson’s writing so compelling is that he knows that the trick to learning any new language is the understanding that languages are not perfect systems. Languages are messy, broken things. They don’t always make sense—not on the surface. But in their imperfections—their irregularities—they offer extraordinary revelations.

In the title story of the collection, “Irregular Verbs,” Johnson translates the messiness of language into the messiness of loss and loneliness. In the Salutean Isles, language develops so quickly and so personally that the community must meet for one hour every day in order to preserve their common tongue; but after the death of his wife, the newly widowed islander Sendiri begins to forget the private language he had shared with her. Johnson renders the threat of that loss in heartbreaking detail: the irregularities of their marital lingo reflect the subtle but inescapable rhythms of two people with genuine love for one another:

keluarga

: to move to a new village

ngantuk

: to call out in one’s sleep

lunak

: to search for something without finding it

Johnson’s fragmented dictionary evokes the scope of a life lived together, the desire to preserve that life and the ineluctable knowledge of its passing.

Other stories in the collection show an equally deft hand. “Heroic Measures” might just be one of the best superhero stories of the past decade, delving into the nature of mortality as an unnamed (but instantly recognizable!) wife must decide if—and how—to pull the plug on the husband she had once thought invincible.

This is the kind of care he gets

, she reflects,

after everything

. Likewise Johnson’s zombie tale, “The Afflicted”—in which Alzheimer’s and senile dementia lead to the all-consuming hunger that evokes the genre—isn’t really a zombie story at all, centering not on the monstrous, but on the slow erosion of the human in those we love. These are not stories that walk the well-worn paths of speculative fiction: they are haunting re-inventions that startle us out of complacency. In these pages you’ll find time travel and magic, afterlives and fairy tale cottages, gods, dragons, Cold War spies and secret police but nevertheless every single tale in the collection feels startlingly fresh.

“Words are the first step we take to turn intentions into reality,” declares Chuck Palahniuk, one of America’s great authors of transgressive fiction. Language is the medium out of which writers birth new worlds. But Palahniuk speaks at length in an interview with Andrew Lawless published at

Three Monkeys Online

about how the flaws in language create the reality of those worlds—what he calls “burnt tongue” moments, moments in which he discovers “a way of saying something, but saying it wrong, twisting it to slow down the reader. Forcing the reader to read close, maybe read twice, not just skim along a surface of abstract images, short-cut adverbs, and clichés.”

Writers dream of a perfect language. But it is the broken language—the irregular language—that allows one to speak most clearly to the heart. It is that language which fractures the superficial, the easily digested, and the generic.

Matthew Johnson knows this. You can see the truth of this knowledge etched deeply in his stories. Stories like pearls: fashioned around a grit of sand, an irritant, an irregularity, out of which comes great beauty. He offers us new worlds, glimpses of futures provocative and profound, traces of histories that never were.

Here is a writer who is not afraid to burn language.

Here is a writer who is not afraid to dream.

Underestimate him at your peril.

—Helen Marshall

January 2014

Oxford, England

RREGULAR

V

ERBS

apiluar

: to let a fire burn out

gelas

: to treat something with care

pikanau

: to cut oneself with a fishhook

It is a well-known fact that there are no people more gifted at language than those of the Salutean Isles. Saluteans live in small villages on a thousand densely populated islands; isolated but never alone, their languages change constantly, and new ones are born all the time. A Salutean’s family has a language unintelligible to their neighbours, his old friends a jargon impenetrable to anyone outside their circle. Two Saluteans sharing shelter from the rain will, by the time it lets up, have developed a new dialect with its own vocabulary and grammar, with tenses such as “when the ground is dry enough to walk on” and “before I was entirely wet.”

It was in just such circumstances that Sendiri Ang had met his wife, Kesepi, and in such circumstances that he lost her. An afternoon spent in a palm-tree shadow is enough time for two people to fall in love, a few moments enough to die when at sea. Eighteen monsoons had passed in between, enough time for the two of them to develop a language of such depth and complexity that no third person could ever learn it, so utterly their own that it was itself an island, without ties to any of its neighbours.

For the ten days of his mourning Sendiri had stayed on the private floor of his house, listening to the fading echoes of his wife’s voice. On the eleventh day he descended to the public floor. That was the longest time thought to be safe: any more away from the great conversation, the hour in the evening in which all Saluteans join in maintaining their one common language, ran the risk of leaving a person stranded, isolated by changes in dialect.

His friend Teman was waiting for him, feeding new coals for the brazier to replace those that had burned cold. It was just like Teman, Sendiri thought, to think of a little thing like that, and for a moment the sight of his old friend cheered him a little.

“Apa kabar?” Teman said.

Sendiri just stared, at first not recognizing the words in Grand Salutean. “How should I be?” he asked after a moment. “I’m here, and she’s not.” As soon as he spoke he regretted it, gave thanks that it was in Teman’s nature to chew his words thoroughly before spitting them out.

“That’s true,” Teman said mildly.

Wincing, Sendiri sat on the reed mat next to his friend. “I’m sorry,” he said. “Thank you for coming here, and for the coals. I’ve gotten very tired of cold rice.”

Teman smiled, clearly relieved at Sendiri’s change of mood. “It’s hard, I know—coming back down. Rejoining the rest of the world.”

Sendiri shook his head. “Ten days, to mourn someone who—someone—it just isn’t enough.”

“A lifetime isn’t enough,” Teman said, smiling sadly. “But it’s all we have.”

That night Sendiri realized he had forgotten a word. He had been dozing, half-asleep, the smell of the squid curing in the thatch above reminding him of his and Kesepi’s last fishing trip together, when suddenly he could not remember the word for the moment, at the end of the long season before the goatfish run, when you think you will die if you have another bite of dried fish. He couldn’t remember which of them had coined it, one of a hundred thousand words they shared, but he knew that it was gone.

That’s ridiculous, he thought. It’s just nibbling the line. . . . He ran through syllables in his mind, trying to catch a memory that slipped and dodged around him, but it was no use: the hook was empty. He shook briefly, reaching out instinctively across the hammock for the warmth that had once reassured him.

Sendiri cast his mind back, remembering conversations they had had, testing the memory like a tongue probing a loose tooth. Mana adalah jaring— What was that word? Suddenly gaps were appearing in his memories. Where there was a Grand Salutean equivalent, the word from that language slipped in; things for which that language had no words were simply gone. Most frustrating, some were words he knew he had remembered that morning. So far only one in a hundred, perhaps, was gone, but more were joining them.

He had never really thought of a language disappearing before. When his mother had died, he and his father preserved their family language, and when his father had died other people—relatives and neighbours—had known enough of it to keep it alive in his mind. Kesepi’s family, though, had been from another village, not witness to their life together, and they had had no children to carry their language on. When it faded from his mind it would be as if it had never been. As if she had never been.

Sendiri sat up, watched the holes in the thatch for the first hint of dawn, cursing the darkness. He would need light for what he had to do, and every moment that passed was his enemy.

Saluteans, on the whole, are not much for writing things down. Their languages are too fluid and mercurial to be caught on paper; only Grand Salutean has a written form, introduced by missionaries of the Southerner to spread his words to the isles and used by village headmen and island chiefs to record debts and proclamations. Sendiri, whose father had been a headman, knew how to read and write, and like most islanders knew how to dry and prepare squid ink to sell to foreigners. Though his and Kesepi’s language was as alike to Grand Salutean as a sting ray is to a monkey he bent its letters to his purposes, torturing and teasing the characters until they could record the sounds that would never be spoken again. He began opening the bundles of cold rice, which friends and relatives had left as mourning gifts, to write on their banana-leaf wrapping. Frantically he wrote word after word, pausing only to mix more ink when the bowl was dry. After some hours the house shook, but he did not look up from his work; only when he heard the ladder up to the private floor creaking did he pause, put down the straightened fishhook he’d been using as a quill.

“Sendiri?” Teman’s voice called from halfway up. Friends though they were, the private floor was inviolate without an invitation.

“What is it?” Sendiri asked.

“The conversation,” Teman said.

Sendiri exhaled sharply, set his work aside carefully. Had it been that long already? The great conversation was held an hour before dusk—he had not even noticed the shadows creeping across the floor. “Just a moment,” he said, his joints complaining as he stood.

He heard Teman climbing back down the ladder, waited until he felt the house sway as his friend’s feet hit the floor below before heading down himself. Teman waited until he had reached the floor, then the two wordlessly passed along the way to the broad walkway that joined his house to the rest of the village. Below, the receding tide had exposed the mud into which the village’s posts were sunk, and the afternoon sun had left it stinking; everywhere nets were hanging to dry, their sharp salty smell burning Sendiri’s nose.

At the public walkway all the villagers were stretched out in the line that made up the great conversation. All voices were speaking in Grand Salutean—in most cases, the only time they would speak it that day. Teman’s uncle Paman, the headman, moved up and down the line, making small talk and ensuring everyone used the correct form, without words or constructions from other dialects creeping in. All Saluteans know that their gift for languages could easily be a curse: without a common tongue, the separate islands of their speech would drift inexorably apart.

Sendiri joined in the conversation gamely, the words tasting flat and oily in his mouth. What, after all, could Grand Salutean express? Village business, fishing advice, weather talk. Teman had returned to his assigned place in the line, so Sendiri made small talk with his neighbours, two nattering old women, Kiri on one side and Kanan on the other; meaningless prattle of rotting walkway boards and late fish-runs. Finally the sunlight reddened, the walkway fell into shadow, and he could go home. The conversation was over.

Freed, he ran back to his house, felt the mangrove poles that supported it sway as he shot up the ladder. He sat down, spat in the ink-bowl to moisten it, picked up his quill and—what had he been about to write? He scanned the leaf he had left on the floor, hoping to find some clue in what he had written before, saw no connections in the list of words he had been writing. Searching his mind for the words he had inventoried that morning, he found even more were gone. It was more than him simply forgetting them, he realized: the language was eroding, an atoll being washed away by the ocean of Grand Salutean. He would have to forego the conversation, then, until the language was preserved. He laughed. What would be lost? No poetry had ever been written in Grand Salutean. It was a deliberately simple language, shorn of all subtlety, a language of nothing but nouns and verbs; no genders, no tenses but now and not-now, no pronouns but I and not-I. It would do him no harm not to use it for a few days.

keluarga

: to move to a new village

ngantuk

: to call out in one’s sleep

lunak

: to search for something without finding it

As the night went on, though, he started to wonder just how long it would have to be. Even with all the words he had lost, he wondered if he could ever write down what was left. He had enough fish oil to burn his lamp for a night, maybe two; more urgently, he was nearly out of banana leaves to write on. Squinting, he made the letters as small as the tip of the hook would allow, and began jotting apostrophes to separate words instead of spaces. Earlier, when he had devised his system of writing, he had not thought about space. Now he cursed his decision to use combinations of letters to represent sounds that did not exist in Grand Salutean, rather than inventing new characters. He was netted now, though. A dictionary had to be consistent, or it was useless; this much he had learned from Grand Salutean.

He kept writing, pushing himself to make the letters smaller and smaller. Hunched over the banana leaf on the floor, his arm held tightly to keep his strokes small, Sendiri’s forearm jerked, scratching a line across the floorboard. He swore, drew the quill back to throw it across the room in anger, when he saw that the ink had dried on the wood without smudging. Of course, he thought. What else would be a suitable record of the language he and Kesepi had shared than the other thing that was theirs alone? Excited, he raised his arms to stretch his back, dipped the quill in the ink bowl, and began writing along the edge of the wall. He worked his way inward as dawn came, and the daylight hours passed; he worked in silence as Teman once again came up the ladder, called his name, called again, and finally left. His quill scratched against the floorboards as he followed an inward spiral towards the centre of the room, always trying to increase his pace, to write words down faster than they could be washed away by his mind’s tide.

Thunder made him look up. It was dark again: lightning flashed through the holes in the thatch, illuminating the room for a moment. Focused on his work, he had not noticed the smell of rain in the air, the sound as it fell on the roof. Now, in the lightning’s flare, he could see puddles sitting on the floor, smudging and washing away most of what he had written. He froze for a moment, rigid with anger; then, too tired even to rage, Sendiri fell to the floor and let himself sleep.

Asleep, he saw himself sitting with Kesepi in their boat, leaning against the palm-stem gunwales on a calm sea. She was speaking, but the words made no sense, and he knew that he had at last forgotten their language entirely. He opened his mouth to speak, then felt something resting in his hand: looking down, he saw that it was the book he had been writing, containing every word the two of them had ever spoken. Flipping through the book, he tried to speak, to say one of the things he wished he had said, but all he could do was string words together. Kesepi, now in a boat of her own, began to drift away. Sendiri called to her, but the words he read from the dictionary had no emotion, and no reaction registered on her face. Even in its perfect state, he realized, the book was just a record, a dead thing without the soul of the language.

He woke from fevered dreams to see Teman sitting on the mat nearby, a bowl of water at his side. His friend rose to his knees and held out the bowl. “Have some of this,” Teman said. “I think you’ve had a fever.”

“Thank you,” Sendiri croaked, then took a drink. He felt a sharp pain as he sat up; the hook he had been using as a quill had stuck in his side, leaving a black ink spot when he plucked it out. “Why are you—”

“You’ve missed two conversations,” Teman said, “and you were moaning last night, loud enough your neighbours could hear. The talk is . . .”

Sendiri nodded. He knew what the talk would be. Sometimes when a person dies, they take the souls of those they love with them to the sea floor; what’s left is just a hantu, a dead, empty shell. To see or even talk to a

hantu

is dangerous, itself an omen of death.

“Maybe I’m not alive,” Sendiri said. “All that’s worth saving is fading away.”

Teman frowned, gestured around at the smudged marks on the floor. “Is that what this was all about?”

“It’s useless, I realize that now,” Sendiri said. “Even if I had all the words, it would be no more alive than a dried fish.” He rubbed the spot where the hook had jabbed him with his thumb. The ink mark was still there, just under his skin. “It needs to live. . . .”

Teman waited for his friend to continue, rose to his feet when he did not. “Well—I shouldn’t even be up here. I hope you’ll forgive me.” He moved to the top step of the ladder, began climbing down.

“No—wait,” Sendiri said. “You have to help me. Help me keep her alive.”

“But you said—”

“No, please. I have an idea. Help me.”

Teman paused at the top of the ladder. “Sendiri—you have to let go. I know how you feel, but you have to let go.”

Sendiri picked up the hook he had been using as a quill, held it up to show to Teman. “Please. Just stay—help me.”

“You have to come out for the conversation. Today.”

“One day. That’s all.”

Teman took a breath, nodded. “All right,” he said.