Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 (78 page)

Read Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 Online

Authors: Christopher Clark

These calumnies referred to an image of the king that by the mid-1840s had established itself ineradicably within the popular imagination. Frederick William IV, a plump, plain, unmilitary man who was known as ‘fatty flounder’ to his siblings and close friends, was the least physically charismatic individual to occupy the Hohenzollern throne since the reign of the first king. He was also the first Prussian king ever to be lampooned in numerous satirical images. Perhaps the most famous contemporary depiction, produced in 1844, portrays the monarch as a portly, drunken puss-in-boots clutching a bottle of champagne in his left paw and a foaming glass in his right, pathetically attempting to ape Frederick the Great against the backdrop of the palace complex at Sans Souci. Having relaxed literary censorship shortly after his accession to the throne, Frederick William reimposed the censorship of images, but it proved impossible to prevent grotesque visual satires of the monarch from circulating widely across the kingdom.

37

Perhaps the most extreme expression of disregard for the person of the sovereign was the

Tschechlied

, a song that recalled the attempted assassination of the king by the mentally disturbed former village mayor Heinrich Ludwig Tschech. Tschech had failed to secure official support for a crusade against local corruption in his native Storkow and fell under the delusion that the monarch was personally to blame for his misfortune. On 26 July 1844, having had himself photographed in a theatrical pose by a daguerreotypist in Berlin, Tschech walked up to the royal carriage and fired two shots at close range, both of which missed. The public initially responded with a wave of sympathy for the king, although it was also widely expected that Tschech would be spared the death penalty in view of his abnormal mental condition. Frederick William was at first inclined to grant him clemency, but his ministers

insisted that he be made an example of. When it became known in December that Tschech had been executed in secret, public sentiment swung against the king.

38

Over the following years a range of Tschech songs circulated in Berlin and across the German states. Their irreverence is captured in the following stanza:

40. Frederick William IV as a tipsy Puss-in-Boots trying vainly to follow in the footsteps of Frederick the Great. Anonymous lithograph.

A fortune ill beyond compare

Befell poor Tschech the village mayor,

That he, though shooting close at hand,

THE SOCIAL QUESTIONCould not hit this bloated man!

39

In the summer of 1844, the Silesian textile district around Peterswaldau and Langenbielau became the scene of the bloodiest upheaval in Prussia before the revolutions of 1848. The trouble began on 4 June, when a crowd attacked the headquarters of Zwanziger Brothers, a substantial textile firm in Peterswaldau. The firm was regarded in the locality as an inconsiderate employer that had exploited the region’s oversupply of labour to depress wages and degrade working conditions. ‘The Zwanziger Brothers are hangmen,’ a popular local song declared.

Their servants are the knaves.

Instead of protecting their workers,

They crush us down like slaves.

40

Having broken into the main residence, the weavers smashed everything they could lay their hands on, from tiled ovens and gilt mirrors to chandeliers and costly porcelain. They tore to shreds all the books, bonds, promissory notes, records and papers they could find, then stormed through an adjacent complex of stores, rolling presses, packing rooms, sheds and warehouses, smashing everything as they went. The work of destruction continued until nightfall, bands of weavers making their way to the scene from outlying villages. On the next morning, the weavers returned to demolish the few structures that remained intact, including the roof. The entire complex would probably have been torched, had someone not pointed out that this would entitle the owners to compensation through their fire insurance.

Armed with axes, pitchforks and stones, the weavers, by now some 3,000 in number, marched out of Peterswaldau and found their way to the house of the Dierig family in Langenbielau. Here they were told by frightened company clerks that a cash payment (five silver groschen) had been promised to any weaver who agreed not to attack the firm’s buildings. Meanwhile two companies of infantry under the command of a Major Rosenberger had arrived from Schweidnitz to restore order; these formed up in the square before the Dierig house. All the ingredients of the disaster that followed were now in place. Fearing that the Dierig house was about to be attacked, Rosenberger gave the order to fire. After three salvos, eleven lay dead on the ground; they included a woman

and a child who had been with the crowd, but also several bystanders, including a little girl who had been on her way to a sewing lesson and a woman looking on from her doorway some 200 paces away. Eyewitnesses reported that one man’s head had been smashed by the shot; the blood-flecked pan of his skull was thrown several feet from his body. The defiance and rage of the crowd now knew no bounds. The troops were driven away by a desperate charge and during the night the weavers rampaged through the Dierig house and its attached buildings, destroying eighty thousand thalers worth of goods, furnishings, books and papers.

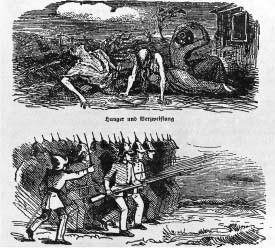

41. How the weavers suffered; and how the state responded. This woodcut published in the radical journal Fliegende Blätter in 1844 refers to the Silesian uprising of that year and bears the caption:

Hunger and Desperation.

The worst was over. Early on the following morning troop reinforcements, complete with artillery pieces, arrived in Langenbielau and the crowd of those who remained in or around the Dierig buildings was

quickly dispersed. There was some further rioting in nearby Friedrichsgrund, and also in Breslau, where a crowd of artisans attacked Jewish houses, but the troops stationed in the city managed to prevent any further tumults. About fifty persons were arrested in connection with the unrest; of these eighteen were sentenced to terms of imprisonment with hard labour and corporal punishment (twenty-four lashes).

41

There were many tumults and hunger riots in the Prussian lands during the 1840s, but none resonated in public awareness like the Silesian weavers’ revolt. Despite the best efforts of the censors, the news of the revolt and its suppression spread across the kingdom within days. From Königsberg and Berlin to Bielefeld, Trier, Aachen, Cologne, Elber-feld and Düsseldorf, there were extensive press commentaries and public discussion. There was a flowering of radical weaver poems, among them Heinrich Heine’s apocalyptic incantation of 1844, ‘The Poor Weavers’, in which the poet invokes the misery and futile rage of a life of endless work on a starvation wage:

The crack of the loom and the shuttle’s flight;

We weave all day and we weave all night.

Germany, we’re weaving your coffin-sheet;

Still weaving, ever weaving!

Numerous essays appeared over the following months analysing the uprising from every possible angle.

The Silesian events caused a sensation because they spoke to a fashionable contemporary obsession with what was coming to be known as ‘the Social Question’ – there are parallels with the almost contemporary British debate that greeted the appearance of Carlyle’s essay of 1839 on the ‘Condition of England’. The Social Question embraced a complex of issues: working conditions within factories, the problem of housing in densely populated areas, the dissolution of corporate entities (e.g. guilds, estates), the vicissitudes of a capitalist economy based on competition, the decline of religion and morals among the emergent ‘proletariat’. But the central and dominant issue was ‘pauperization’, the progressive impoverishment of the lower social strata. The ‘pauperism’ of the pre-March era differed from traditional forms of poverty in a number of important ways: it was a mass phenomenon, collective and structural, rather than dependent upon individual contingencies, such as sickness, injury or crop failures; it was permanent rather than

seasonal; and it showed signs of engulfing social groups whose position had previously been relatively secure, such as artisans (especially apprentices and journeymen) and smallholding peasants. ‘Pauperism,’ the

Brockhaus Encyclopaedia

noted in 1846, ‘occurs when a large class can subsist only as a result of the most intensive labour…’

42

The key problem was a decline in the value of labour and its products. This affected not only unskilled labourers and those who worked in the craft trades, but also the large and growing section of the rural population who lived from various forms of cottage industry.

The deepening misery was reflected in patterns of food consumption: whereas the inhabitants of the Prussian Rhine province consumed on average forty-one kilos of meat per annum in 1838, this figure had fallen to thirty by 1848.

43

A statistical survey of 1846 suggested that between 50 and 60 per cent of the Prussian population were living on or near the subsistence minimum. In the early 1840s, the deepening of poverty across the kingdom triggered a moral panic among the Prussian literary classes. Bettina von Arnim’s

This Book Belongs to the King

, published in Berlin in 1843, opened with a sequence of fanciful literary dialogues whose common theme was the social crisis in the kingdom.

44

Included in the text was a detailed appendix recording the observations of Heinrich Grunholzer, a 23-year-old Swiss student, in the slums of Berlin. Over the three decades between 1816 and 1846, the population of the capital had risen from 197,000 to 397,000. Many of the poorest immigrants – wage labourers and artisans for the most part – settled in the densely populated slum area on the northern outskirts of the city known as the ‘Vogtland’ because many of the earliest arrivals hailed from the Vogtland in Saxony. It was here that Grunholzer recorded his observations for Arnim’s book.

In an era that has become inured to the authenticity-effect of documentary, it is hard to recapture the fascination of Grunholzer’s bald descriptions of life in the most desolate corners of the capital. He spent four weeks combing through a few selected tenements and interviewing their occupants. He recorded his impressions in a spare prose that was paced out in short, informal sentences, and integrated the brutal statistics that governed the lives of the poorest families in the city. Passages of dialogue were woven into the narrative and the frequent use of the present tense suggested notes scribbled

in situ

.

In basement room no. 3, I found a woodchopper with a diseased leg. When I entered, the wife grabbed the potato peelings from the table and a sixteen-year-old daughter withdrew embarrassed into a corner of the room while her father began to tell me his tale. He had been rendered unemployable while helping to construct the new School of Engineering. His request for assistance was long ignored. Only when he was economically completely ruined was he granted a monthly allowance of 15 silver groschen [half a thaler]. He had to move back into the family apartment, because he could no longer afford an apartment in the city. Now he receives two thalers monthly from the Poor Office. In times when the incurable disease of his leg permits, he can earn one thaler a month; his wife earns twice that amount, his daughter can bring in an additional one-and-a-half thalers. But their accommodation costs two thalers a month, a ‘meal of potatoes’ one silver groschen and nine pennies; at two such meals a day, this comes to three-and-a-half thalers per month for the staple nourishment. One thaler thus remains for the purchase of wood and for all that a family needs, aside from raw potatoes, in order to survive.

45