Introducing Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (Introducing...) (4 page)

Read Introducing Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (Introducing...) Online

Authors: Elaine Iljon Foreman,Clair Pollard

Step 4: manage your unhelpful thinking

Look again at the diagram at the beginning of this chapter. You can see how negative thoughts about not sleeping or general worries can lead us to feel frustrated, worried or stressed, to have increased muscle tension or to behave in less helpful ways. All of these things prevent us from sleeping well. In order to change the way we sleep, we need to alter the way we think and behave in relation to our thoughts.

Deal with low mood or anxiety.

Mood disorders such as anxiety, panic or depression can cause us problems with sleep. Other chapters in this book will help you to find ways of overcoming these problems. Use our questionnaires to help you work out what the problem might be. Consistently waking very early in the morning and being unable to get back to sleep can be a symptom of depression. If you are worried that you may be severely depressed or anxious, talk to your doctor about getting some further help.

Chapter 4

tells you about coping with anxiety,

Chapter 6

tells you more about depression and how to deal with it, while

Chapter 9

suggests additional resources which you might find helpful.

Reduce worry.

We have already said that many people find that lying awake worrying prevents them getting to sleep. You can help yourself by noticing when you are falling into a spiral of worry and reminding yourself that this is not the time to be worrying. If you are frequently in the habit of worrying in bed then fix a set period within your bedtime routine as ‘worry time’, in which you give yourself the opportunity – and indeed permission – to think about all those things your mind might be worrying about. Try writing them down and dealing with the things that can be dealt with before you go to bed. Use the ‘worry tree’ described in

Chapter 4

. Once you have had your worry time for the night, be firm with your mind if the worry tries to start again. Focus and really concentrate on something more pleasant and relaxing, perhaps a favourite memory, planning a holiday or even just counting in your head. Remember that what you focus on expands, so it should be something that helps you switch off, not wakes you up. If you worry that you will forget things, keep a pen and paper near the bed. Write things down, then once again,

move on

to something else. Remind yourself that there’s no chance you’ll forget them, it’s all written down, and that now is not your worry time – it will just have to wait to tomorrow’s slot.

Chapter 4

tells you more about managing worry.

In bed, trying to sleep, is NOT the time for trying to think through problems or worries

Tackle worry about not sleeping.

If you lie awake saying to yourself ‘I’ll never manage work tomorrow if I don’t sleep’, you’ll find it harder and harder to switch off and relax. This can become a vicious cycle as shown in the diagram earlier in this chapter. You may need to work on breaking this cycle. Remind yourself that although you may feel tired this will not necessarily affect your performance. Part of sleeping is allowing your body to physically rest so make this your goal rather than sleep. Relax your muscles and begin focusing on relaxing thoughts. Move your alarm clock so that you can’t easily keep checking the time.

Nightmares

Nightmares can be very frightening. Some people can be afraid to sleep in case they have one. Once again there are a number of theories as to why some of us have nightmares, while others never have any (or at least don’t remember them). It’s generally agreed that when we are upset, frightened or distressed we’re more likely to experience nightmares. If you do wake up from a bad dream, you need to first remind yourself it really was only a dream, and that your mind is just working things out in its own way. Writing down the dream can also minimize the hold that it has on you. Seeing it on paper, weird and not making much sense, can be a way of making it feel smaller and less important. You can allow yourself to just look in a detached way at the strange things your mind comes up with, without attributing any additional sinister meanings to them.

Should I use sleep medication?

Your doctor can prescribe various medications to help you sleep. However, over time some can be addictive and can leave you feeling tired and ‘hungover’ the next day. Over time the body can become used to them, meaning that you need higher doses. The same can be true of medications which you can buy over the counter without prescription. Sleep medication should really only be used for short-term relief of acute sleep problems when, for example, someone is so distressed that they cannot sleep at all, night after night.

There are also herbal remedies available which some people find helpful. Again, however, it is preferable for you to develop improved routines and habits to help you to sleep naturally than to rely on any kind of substance to help your sleep.

So how could applying these techniques help Simon and Robert?

Case study – Robert

Robert needs to tackle his worry in order to switch off and sleep at night. He implements the techniques suggested here by starting a good bedtime routine an hour and a half before bed. Robert and his wife decide to eat dinner slightly earlier in the evening to allow time for Robert to relax and deal with worry before going to bed. Once he’s eaten, Robert sits down and allows himself half an hour of ‘worry time’ to think about the things that might otherwise keep him awake. He uses the worry exercises from

Chapter 4

to help him to decide whether he can do something practical to solve each problem now, or whether he needs to make a plan to solve it in the future. He makes notes so that he knows there’s no danger of him forgetting things. Robert spends half an hour on his worry time exercise, making sure he’s covered everything he might worry about. He then spends some time quietly listening to music which both he and his wife find is relaxing, before they go to bed together. Robert moves his clock so that he can no longer see it from the bed.

Once in bed if he finds his mind heading off in the direction of his worries, he now firmly tells himself that this isn’t the time to worry, that there’s nothing he can do about it right now, and that he’s already planned how to deal with everything he needs to for tomorrow. If something comes up, however, that Robert really wants to remember, and that he knows he didn’t include in his worry time, then, if he can’t move on from it, he writes it down on the piece of paper he now keeps next to the bed, before allowing himself to move on to something else.

At first this whole process proves pretty difficult. Robert keeps catching himself starting a particular worry, and has to remind himself that he has dealt with it for now. He has to deliberately encourage his mind to move on to something else. Rather than getting frustrated with the repetition, he reminds himself that it takes time and patience to break habits. He considers reading

Chapter 5

for more ideas on beating bad habits. If after 15 minutes he’s still awake, Robert gets up, goes into the front room and listens to music for a while before coming back to bed when he feels tired. Over time Robert’s sleep starts to improve and he finds he is more able to deal with the worry that used to prevent him from sleeping.

Case study – Simon

Simon also needs to apply the principles of

sleep hygiene

in order to improve his poor sleep. Simon uses these techniques alongside those suggested in

Chapter 6

to help lift his low mood. He realizes that he needs to get more active during the day in order to sleep at night. He also has to stop napping during the day. This proves difficult while he has so little to do, so Simon starts to structure his day, planning his time to include both tasks and leisure activities. As he learns to keep busy during the day, he finds he no longer feels so tired and sleepy all the time. Simon cuts down on the time he spends watching television, and arranges times to see friends, walk the dog and go swimming.

Like Robert, he implements a bedtime routine which he too finds relaxing. He makes sure he is strict with himself about the times he goes to bed and gets up. Simon and his partner used to watch television in bed at night, so they agree to move the television out of the bedroom, and only switch it on when there is something they really want to watch. Simon also decides to cut out alcohol in the evening, and only have a drink or two over dinner at the weekend.

Not surprisingly, Simon finds these changes difficult to stick to at first. He’s not used to sleeping at night, and initially finds that he doesn’t sleep much. It’s then very hard for him to stay awake during the day and he needs to make sure he keeps busy in order to force himself to stay awake. Simon asks his friends to help with this. Eventually, Simon finds that he’s able to fall into a more natural pattern and sleep at night. His increased activity during the day starts to improve his mood, which also helps him to stop worrying and sleep better. Simon’s motivation increases and he becomes more positive about continuing his search for another job.

Finally, though things are very much improved, Simon and his partner decide that now is not the best time to start a family, as they remember the words of Leo Burke:

People who say they sleep like a baby usually

don’t have one

.

4. Managing anxiety

From ghoulies and ghosties

And long-leggety beasties

And things that go bump in the night

,

Good Lord, deliver us!

Traditional Cornish prayer

Understanding anxiety

The internet offers around 46.5 million answers to what anxiety is all about! So that you don’t have to go through them all (at 5 minutes per website that’s around 450 years of your time) in this section we condense it down to the basic essentials:

- What it is

- Where it comes from

- What forms it takes and, most important of all …

- What you can DO about it.

What is it?

Anxiety is often described as a feeling of worry, fear or trepidation. But it’s much more than just a feeling. It encompasses

feelings or emotions, thoughts and bodily sensations

.

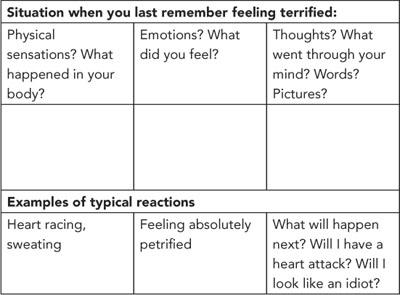

You might be more sensitive to one or two of these. Remember when you last felt really scared? Write down what you remember noticing, and then look at the examples we have given. Don’t worry if one column’s blank – it’s common not to notice everything when you first start looking at your emotions, thoughts and physical feelings.

Occasional anxiety is absolutely normal within our everyday experience. If you didn’t feel anxious, ever,

that

would be something to worry about! Life presents us with challenges, which we aren’t always confident we can handle, so a degree of anxiety is natural. The challenges can be stressful events including actual danger, happening in the real world, and/or the things our minds conjure up, such as what

if

a catastrophe

did

occur – like meeting those ghoulies and ghosties which we mentioned at the start of this chapter.

Feelings or emotions

When we experience severe anxiety we usually feel terrified. While sometimes it is quite straightforward to identify what it is that we are scared of, at other times we just get an overwhelming feeling of panic. But whether you love or hate this feeling depends to a great extent on your personality and the context.

Believe it or not some people seek strong sensations, and for these people sometimes the more powerful, the better! Experiencing high anxiety can be pleasurable, even though that might sound peculiar. Think of horror films, amusement parks or ‘extreme sports’ holidays. Certain people love the adrenaline rush these activities provide. The key is that usually the enjoyment is linked to it being a time, place and activity that they have chosen. They would probably be less enthusiastic about something that was happening to them uninvited, unwanted, out of their control and downright dangerous!

Thoughts

We all usually try to make sense of our environment, and to understand what is happening to us. It can be really frightening not to know what is happening, and to anticipate that whatever is going to happen next will be even worse. Anyone experiencing feelings of panic and terror is likely to try to figure out why it’s happening, and what it means. How we make sense of our world is what tells us whether it is safe or dangerous. Shakespeare neatly summed this up, writing in

Hamlet

, ‘there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so’.

So the link between thoughts and emotions is already becoming apparent – if you

think

something is

really

dangerous, you are likely to be seriously scared of it. People watching a horror movie are less likely to enjoy it if they then start looking out for aliens and monsters when they leave the cinema, while those who recognize it as being ‘only make believe’ can safely enjoy the scariness in the confines of the cinema, knowing that in reality there are no such dangers.

Bodily sensations

It can be quite astonishing to discover how many different sensations can be triggered by anxiety and how many different parts of the body can be affected. You may get just a few of these or most of them. The most common sensations are:

- Your heart may beat faster and harder

- Your chest may feel tight or painful

- You may sweat profusely

- You may tremble or have shaking arms and legs

- You may have icy cold feet and hands

- You may have a dry mouth

- You may have blurred vision

- You may need to go to the toilet or have a churning or fluttering stomach

- You may have a horrible headache

- You may feel that you’re ‘not really here’ or that you are somehow out of your body, looking down on everything, detached from your surroundings

- You may feel as if everything is very unreal

- You may feel dizzy, light-headed or faint

- You may feel you have a lump in your throat or that you can’t swallow

- You may feel nauseous – you may even vomit

- You may feel tense, restless or unable to relax

- You may have general aches and pains.

As we mentioned, it is normal to experience anxiety when we feel we are in danger. Your body responds with the ‘triple F’ reaction, Fight, Flight or Freeze. It’s a really important automatic response – your body does it all by itself. The 3 Fs are linked to the survival of our species over the years. Take the example of disturbing a hungry wild animal out in the bush. Depending on both you and the type of animal, you might try to fight it, to run away as fast as you could, or to keep stock still in the hope that it had poor eyesight and wouldn’t charge at you. Which of the 3 Fs do you reckon you’d choose?

In situations you perceive as dangerous, your body produces a whole range of chemicals (including adrenaline) which trigger all of the physical symptoms above. These bodily changes are what have helped the human race to survive. The chemicals released cause physical changes which enable us to run far faster than otherwise, have greater strength, and generally have a better chance of defending ourselves and our loved ones. That’s great for an objective danger like a wild animal, but not particularly helpful when the perceived danger is more of a social one, like being afraid you will make a fool of yourself or a (most likely unfounded) fear of a physical catastrophe such as having a heart attack or brain haemorrhage.

In a moment we will go on to look at different specific types of anxiety problem. Each links to a range of thoughts about what is happening. So for instance, if you suffer from panic attacks you’ll probably fear that when you experience one something terrible will happen such as a heart attack, or a brain haemorrhage, or that you’ll go hysterical and make a total fool of yourself. If your problem is obsessive-compulsive disorder, then your fear may be that if you don’t do things in the right order, or clean or check sufficiently, then something dreadful will befall you or those close to you. A key feature of post-traumatic stress disorder is that the person tries to avoid reminders of the trauma. They frequently think that if they’re reminded too sharply of what happened, they’ll start re-experiencing it, and that the feelings might be more than they can bear. In this chapter we will look at different anxiety disorders in turn. However, the techniques we discuss to manage anxiety are general ones. If your anxiety problem is more severe or specific then the further resources in

Chapter 9

will help you discover where else you might get help.

If you are someone who feels anxious a lot of the time, or your anxiety is so intense it’s starting to affect your everyday life, you may be suffering from one of the anxiety disorders. While we mentioned that anxiety is normal in certain situations, it becomes a problem when:

- It is out of proportion to the stressful situation

- It persists when a stressful situation has gone

- It appears for no apparent reason when there is no stressful situation.

Where to start with anxiety:

1. Try to understand your symptoms

2. Talk things over with a friend, family member or health professional

3. Look at your lifestyle – consider cutting down or steering clear of alcohol, illicit drugs and even stimulants like caffeine

4. Apply some of the CBT techniques in this chapter.

It’s quite common for people who are suffering from anxiety to also have symptoms of depression. If this is true for you then

Chapter 6

on managing depression may be helpful for you.

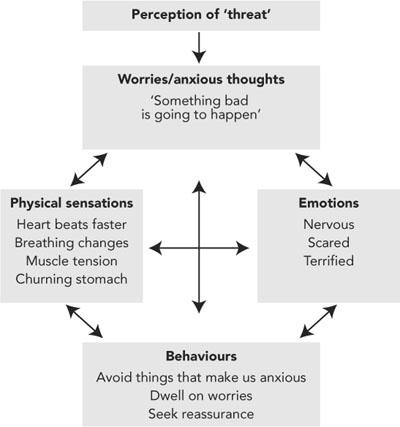

How CBT understands anxiety

CBT looks at how our thoughts, emotions, physical sensations and behaviours all interact to maintain our anxiety. When we perceive a ‘threat’ of any kind – whether that is a fear of something that is happening right now or a worry about something that might happen in the future – our bodies and minds react in the ways we have looked at in the diagram on

here

. When we notice the physical sensations of anxiety we assume that this means there really is a threat (even if in reality there is none) and so we get more anxious thoughts. This in turn leads to enhanced physical sensations as our bodies respond to our perceptions. When we are scared of something we naturally avoid it. However this in turn can lead us to believe more strongly that there really is something to be scared of – and by avoiding it, we never get the chance to test out our fears. Our anxiety about that situation therefore increases. Often we dwell on our fears and worries in order to try to make sense of them, keep ourselves safe or stop bad things happening. However, this habit is most often unproductive and simply serves to increase our anxiety without actually improving or changing our situation. Seeking out reassurance from people close to us, searching the internet, or consulting professionals might make good sense if we do it once and it serves to calm our fear in a lasting way. However, what tends to happen when people suffer from anxiety is that they will seek reassurance, feel better for a short time, but then keep needing more reassurance. This means that nothing changes and they never develop more effective, lasting ways of managing their anxiety.