Into That Darkness: From Mercy Killing to Mass Murder (23 page)

Read Into That Darkness: From Mercy Killing to Mass Murder Online

Authors: Gitta Sereny

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #Military, #World War II, #World, #Jewish, #Holocaust, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Ideologies & Doctrines, #Fascism, #International & World Politics, #European

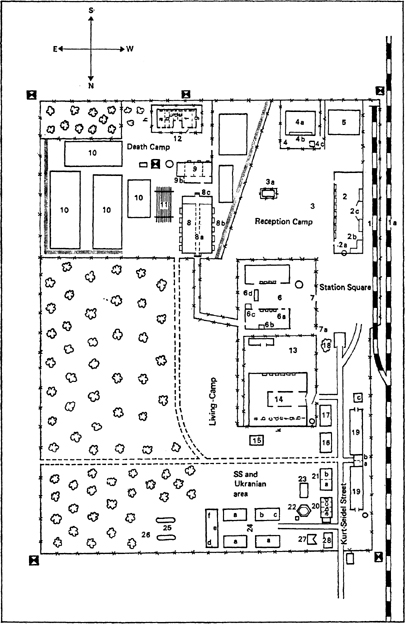

TREBLINKA EXTERMINATION CAMP

R

ECEPTION

C

AMP

(i) The ramp (station platform) where “Blue Command” worked, (1a) Line to Treblinka Labour Camp, about 2 kilometres away – a separate installation, its prisoners mostly Christian Poles, not Jews

(2) Large sorting barracks for goods, eventually disguised (on side facing railway) as a station, with (2a) fake clock and (2b) fake ticket windows. (2c) Sliding doors used only after victims had been removed

(3) Sorting Square, where “Sorting Command” worked. (3a) Latrine

(4)

Lazarett

(fake hospital). (4a) Pit for burning bodies, (4b) low earth bank, and (4c) shelter for guard

(5) Pit for corpses from transports

(6) Undressing barracks, where “Red Command” worked, for men and (6a) women. (6b) Cash-desk, (6c) hair-cutters, (6d) notice-board displaying instructions

(7) Main entrance. (7a) Entrance for guards. (7b) Gate leading to (7e) “The Tube”. (7d) Storage for bottles, pots, pans etc.

D

EATH

-

CAMP

(8) “The Tube” led directly to (8), new gas chambers, entered through small doors (8a) from a central passage, emptied of bodies through larger doors (8b). The engine room (8c) supplied carbon monoxide, exhaust fumes

(9) Old gas chambers. (9a) Engine room

(10) Burial pits, first used with lime, then emptied and refilled with ashes, the bodies having been burnt on “the Roast”.

(11) “The Roast”. (11a) Pit used for burning experiments. (11b) Unused pit

(12) Living quarters for Jews working in Death-camp. (12a) Women, (b) doctors, (c) Kapo, (d) showers, (e) latrine, (f) men, (g) kitchen and (h) outside laundry

L

IVING

C

AMP

(13)

Appelplatz

(square for roll-call)

(14) Living quarters for work-Jews. (14a) Gold-Jews, (b) women, (c) joiners, (d) tailors, (e) shoemakers, (f) Kapos, (g) sick-bay, (h) laundry, (i) kitchen, (j) sleeping quarters, (k) barred windows, and (1) latrine

(15) Stables

(16) Textile store

(17) Bakery

(18) Coal pile

SS

AND

U

KRAINIAN

A

REA

(19) Living quarters and mess for

SS

. (19a) Munitions, (b) showers, and (c) petrol pump

(20) Building containing (a) air-raid shelter, (b) sick-bay, (c) dentist, and (d) barber

(21) Domestic staff, (a) Polish girls, and (b) Ukrainian girls

(22) Zoo

(23) Building which became workroom for Gold-Jews

(24) “Max Bielas Barracks” – living quarters for Ukrainian guards. (24a) Sleeping quarters, (b) doctor, (c) barber, (d) kitchen, (e) mess and (f) day-room

(25) Potato cellars

(26) Exercise area for Ukrainians

(27) Cellar, use unknown

(28) Kommandant’s quarters

The camp was surrounded by an inner fence of barbed wire camouflaged with branches, 3–4 metres high, a space with tank obstacles, 40–50 metres wide, and an outer fence of barbed wire.

The single railway track laid from Treblinka town station into the camp is now represented by great beams of wood laid along its course. I walked along it, trying to visualize what the people in the freight-cars would have seen. The snow from the night before had frozen on the ground and on the trees; it was not unlike the approach to a ski resort, quiet, clean, green and white. Of course, most of the trains had no windows, but there would have been cracks between doors, or holes in walls. Did the view reassure them? Did they allow themselves to believe that this little track, running between these lovely trees – for here the trees were left standing – couldn’t lead to anything too bad?

Whether their illusion of reassurance (if they felt it) was prolonged or destroyed upon reaching the ‘ramp’ – the arrival platform – depended on when they arrived and who they were.

If they were Western Europeans, their arrival was at no time grossly alarming; and after the ramp had been disguised as a railway station complete with flower-beds, in the second half of the year, it became even more deceptive. Richard Glazar, a survivor who was one of a preferential Czech transport and came on a passenger train, said, “We all crowded to look out of the windows. I saw a green fence, barracks, and I heard what sounded like a farm tractor. I was delighted.” Medical orderlies were lined up to “care for” the old and sick; polite voices bade them disembark at their leisure, but in an orderly fashion, please; and, except by an oversight, there was not a whip to be seen–a whole macabre fakery. These people might well have been confirmed in the belief that they had reached a resettlement centre where they could rest before being assigned to places of work and residence.

But if they were Eastern Europeans, whether during the first or the second half of the year, then the moment the train stopped they saw the Ukrainian guards with their whips lining the platform, the

SS

drawn up behind them; all this deliberate, to provoke instant dread and foreboding. They were literally whipped out of the trains, and hurried and harried until the moment of their death.

These were the images which pressed on the mind when I entered what had been the camp proper and began to walk along the path to the gas chambers – the tube; as in Sobibor, the

SS

called it the “Road to Heaven”.

Four people had come with me to Treblinka; a driver and an intelligent young interpreter, Wanda Jakubiuk; sixty-five-year-old Francizek Zabecki, former member of the Home Army

*

and traffic superintendent of Treblinka (village) railway station, and Berek Rojzman, sixty years old, who lost his whole family in Treblinka and is the only survivor of the camp still living in Poland.

It was a bitingly cold day – in spite of fur-lined boots my feet were soon freezing. After thirty minutes or so of walking around on our own Wanda and I came face to face among the trees. “The children,” she burst out, with exactly the words which were dominant in my mind: “Oh my God, the children, naked, in this terrible cold.” We stood for a long moment, silent, where they used to stand waiting for those ahead to be dead, waiting their turn. Often, I had been told, their naked feet had frozen into the ground, so that when the Ukrainians’ whips on both sides of the path began to drive them on, their mothers had to tear them loose.…Standing there, it was unbearable to remember, yet both Wanda and I felt that this deliberate effort to visualize the reality of a hell none of us can really share was what we had to do – it was the least we had to do.

The memorial built by the Poles on the site of the death-camp is a fine one: thousands of granite slabs, the different sizes representing the number of people killed from different cities and towns in Europe. The natural rock is scattered in what seems to be a random way, stones representing tiny villages next to larger ones standing for towns and cities, and all of them dwarfed by the huge rugged rock which stands for the more than three hundred thousand people from Warsaw who died here.

Franciszek Zabecki’s work during the war as traffic supervisor of Treblinka station – an important junction for German military traffic to the East – and as a vital informant for the Polish underground, makes him a unique personality from the historical point of view: the only trained observer to be on the spot throughout the whole existence of Treblinka camp. He was placed there originally to report on the movement of troops and equipment. He lived with his wife and their three-year-old son in the first-floor flat of the station building. His duties were the registration of all trains and way-bills and the counting of the carriages of all military trains, carried out round the clock with the help of an assistant traffic-controller also working for the Home Army. He was thus a witness of all the transports that passed through the station on their way into the camp.

Pan Zabecki began working for the railway in 1925, when he was eighteen. After a brief spell as a prisoner of war in 1939, he was manoeuvred by the underground into the vacant job at Treblinka station in May 1941. He spent the first year consolidating his position in the district, collecting the required data for the underground on the Germans’ development of the important line between Kossov, near Treblinka, and Malkinia, a staging-point for troops and material travelling east, and making contacts, including some with German railway personnel.

In the early spring of 1942 the Germans established a small labour camp for Poles near a stone quarry deep in the woods, about four kilometres from the station. “The first inkling we had that something more was being planned in Treblinka,” Pan Zabecki said, “was in May 1942, when some

SS

men arrived with a man called Ernst Grauss who – we found out from the German railway workers – was the chief surveyor at the German District

HQ

. They spent the day looking around and the very next day all fit male Jews from the neighbourhood – about a hundred of them – were brought in and started work on clearing the land. At the same time they shipped in a first lot of Ukrainian guards.”

This whole eastern district of Poland – in a triangle of which were placed three of the four extermination camps – lies very close to the Russian border.

“Many of the Ukrainians had friends near here in the village closest to Treblinka, a hamlet of two hundred inhabitants called Wolga-Oknaglik. It’s a tiny place, no school or church – the children go to school six kilometres away in Kossov. But it was from there we began to hear rumours. We heard that a large area of wooded land had been fenced in and some of it was being cleared; a barrack was being built, we were told, for German personnel, and another for the workers. And a well had been sunk for water. Within an incredibly short time we heard that not only had a camp been set up, but we also saw them lay tracks from our main line into the fenced-off area.

“It is difficult to describe to you now the atmosphere of that time. When I say we heard rumours, I mean a whole series of unconnected and contradictory wild-sounding interpretations of events. Some things, of course, we saw for ourselves. Others we felt sure were only guesses or inventions about what went on behind those fences.

“It was said that it was to be another labour camp; a camp for Jews who would work on damming the River Bug; a military installation; a staging or control area for a new secret military weapon. And finally, German railways workers said it was going to be an extermination camp. But nobody believed them – except me.”

The extermination camps at Belsec and Sobibor had by then been functioning for some time, “But we hadn’t heard of them at all,” said Zabecki. “You see, from the point of view of the Home Army, for instance, Sobibor was in the district of Lublin; each district was autonomously administered and there was no communication between the districts. However, I had vaguely heard of Auschwitz – I didn’t really know

what

went on there, but I told my colleagues that

I

believed what the German railway workers said. [There was no extermination installation at Auschwitz at that time, so it was indeed rumours he had heard.] Of course one had no conception of what ‘extermination camp’ really meant. I mean, it was beyond – not just experience, but imagination, wasn’t it?

“On July 23, 1942,” he continued, “my colleague, Josef Pogonzelski, was traffic superintendent for the day. The day before we had had a telegram announcing the arrival of ‘shuttle trains’ from Warsaw with ‘resetters’. This wire was followed by a letter-telegram giving a schedule for the daily arrival of these shuttle trains as of the following day, July 23. We were waiting for them as of the early morning, wondering what they were. At one moment two

SS

men came – from the camp I think – and asked ‘Where is the train?’ They had been informed by Warsaw that it should already have arrived, but it hadn’t. Then a tender came in – the sort called a railway-taxi – with two German engineers, one was called Blechschmied, the other, his assistant, Teufel. They had been sent ahead to guide the first trains along the new track, into the camp.