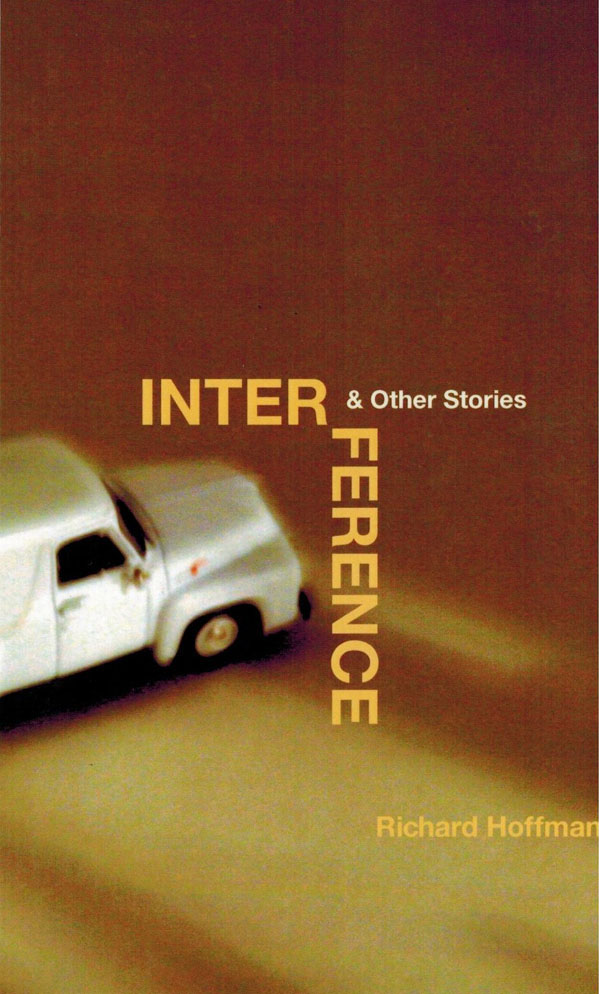

Interference & Other Stories

Read Interference & Other Stories Online

Authors: Richard Hoffman

© 2009 by Richard Hoffman

First Edition

Library of Congress Control Number: 2008934509

eISBN: 978-0-89823-297-4

American Fiction Series

Cover design by Megan McCleary

Author photograph by Mike Lew

The publication of

Interference and Other Stories

is made possible by the generous support of the McKnight Foundation and other contributors to New Rivers Press.

For academic permission please contact Frederick T. Courtright at 570-839-7477 or

[email protected]

. For all other permissions, contact The Copyright Clearance Center at 978-750-8400 or

[email protected]

.

New Rivers Press is a nonprofit literary press associated with Minnesota State University Moorhead.

Wayne Gudmundson, Director

Alan Davis, Senior Editor

Donna Carlson, Managing Editor

Allen Sheets, Art Director

Thom Tammaro, Poetry Editor

Kevin Carollo, MVP Poetry Coordinator

Liz Severn, MVP Fiction Coordinator

Frances Zimmerman, Business Manager

Publishing Interns: Samantha Jones, Andrew Olson, Mary Huyck Mulka

Interference

Book Team: Michael Beeman, Kayla Lundgren, Tarver Mathison, Alyssa Schafer

Editorial Interns: Michael Beeman, Nathan Logan, Kayla Lundgren, Tarver Mathison, Mary Huyck Mulka, Amber Olds, Jessica Riepe, Alyssa Schafer, Andrea Vasquez

Design Interns: Alex Ehlen, Andrew Kerr, Erin Malkowski, Megan McCleary, Lindsay Stokes

Printed in the United States of America.

New Rivers Press books are distributed nationwide by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution.

www.cbsd.com

for Kathi, as always

GUY GOES INTO A THERAPIST'S OFFICE

FROM THIS DISTANCE, AT THIS SPEED

GUY GOES UP TO THE PEARLY GATES

T

he bikes buzzed past trooper Larry Powell in the unmarked car, three of them, then another two, and then after a moment one more, all of them going ninety, maybe more, weaving in and out of the three lanes of interstate traffic, so he hit the blue light and siren and pursued. Ahead, he saw several drivers swerve as they became aware of the sudden noise and color of the bikes whizzing past themâa dangerous set of circumstances, goddamn it, somebody could get killed. He was on the straggler quickly, moving right up behind him, holding steady, until the green and yellow crotch rocket, a Kawasaki, a “rice-burner,” they would have called it at the barracks, slowed and pulled over just beyond a fenced overpass festooned with American flags and a sign: “Welcome Home Pfc. Bruce McHale”. Powell radioed his whereabouts and action as he rolled to a stop on the shoulder about ten yards beyond the bike.

He put on his troopers hat and walked back to the rider. “Dismount, please.” No response. “Get off the bike, sir. Now.” The rider dismounted. “And remove your helmet, sir.”

The rider was a young man, maybe eighteen, maybe younger. Sir. Ha. He held the bright enameled shell of the helmet under his arm. Dark eyes. Eurasian features.

“License and registration.”

“Officer, can I just sayâ“

Powell raised his hand so quickly the young man flinched. “Don't,” Powell said. “Lets have it. Right now.” His hand moved from the stop to the give-me position; he even snapped his fingers. “Remain here. You understand? You seem to have a little trouble following simple directions“

Powell returned to the car, ran the computer check. Holder, Lee. Date of birth, 9/18/87. Clean. The bike was, of course, a rental.

It took another moment before the date registered: Holder had been born on the same day as Powells late son, Franklin, though he was three years younger than Franklin would now have been. Powell watched the young man in the rearview mirror and thought his posture arrogant, arms crossed over his chest as if to say to passing drivers that its worth the price of a stupid ticket once in a while to have some fun. Not like the rest of you losers. The young man ran the toe of his sneaker back and forth in a little half-moon in the ground, and Powell took this to mean he was disinterested and impatient to get this over with and be on his way.

Well, let him wait then, Powell thought, let him stand there shifting his weight back and forth. This is what his girlfriend Didi would call a teachable moment. A school psychologist, she would have weighed in here on the value of consequences, and on the necessity of spelling out the connection between action and consequence. No argument from Powell. When Franklin hit the bridge abutment and broke his neck, he'd been going eighty, and the autopsy showed a blood alcohol level of 0.25, making it questionable whether or not Franklin had even been conscious when he lost control of the car. Even so, just days after his burial, his friends had held a night-time party on his grave, leaving behind a copy of the yearbook, a dozen beer cans, and an empty quart of Jim Beam. Somebody'd puked, too. Some memorial. It seemed fair to say that they had trouble connecting actions to consequences. The difference between him and Didiâaside from the aggravating fact that she didn't think they should be marriedâwas that she was ready with explanations having to do with the slow maturation of the pre-frontal lobe, where the kind of cognition that weighs actions and consequences occurs; for Powell, it was just needless stupidity and it made him angry. The other difference, of course, was that Franklin was not her son.

Franklin's mother, Liz, who was raised and still had family in Minnesota, moved there even before the divorce was final. Whenever he thought about it, Powell chose to keep it simple: the marriage did not survive the death of their only child. Period. It was true that she'd said he was too hard on their son and blamed him for the boys defiant wildness, which she saw as the cause of the accident; and it was also true that Powell had never managed to talk himself out of his conviction that Liz was no good at setting limits and that if she couldn't handle the boy's defiance as he got older, then she should not have interposed herself between him, the stronger disciplinarian, and their son. But those mutual recriminations were much too painful to revisit, andâeven more painfullyâirrelevant now.

Â

“So why don't you want to get married, Miss Texas? Don't people get married down there where you grew up?”

“I already told you. I don't see why.”

“Because it's a commitment.”

“Larry, I'm not going anywhere. What is with this marriage thing? Right now I think it's great having a lover. And you're a great lover.”

“Oh throw me a bone, why don't you?” Powell smirked, but he was pleased to hear she thought so. “I thought women were supposed to want to be married. “

“Darlin', sometimes you are one big beefcake bimbo, you know that? Let me tell you something. There are only two things you need to remember about women. The first is that we're just like you. And the second is that we're different creatures entirely because we're always having to contend with what you men imagine us to be.”

“Is that supposed to clarify things?”

She raised herself onto one elbow and pinched lightly at his left nipple. She often played around with his nipples, something no woman had ever done before. He didn't find it unpleasant, but it didn't do much for him either. “Darlin', marriage is just the next stop on the bus you're on. But you know what? It's a tour bus. It goes in a circle. So, no thanks. I want you in my life, Larry. I do. But marriage? No thanks.”

Powell made a face at her that he hoped was an equal mix of disappointment and reproach, a look that would say he was hurt but that she'd blown it, that it was her loss, and brushed her hand away from his chest.

Â

His helmet under his arm, the young man was approaching the car now, no doubt to ask if he could have his ticket and be on his way. Powell watched him in the rearview mirror for a moment and gathered himself for the display of power and authority called for in this situation. It was straight out of academy procedures and it always worked. He stepped from the car, wheeled, and pointing at arm's length as he strode toward the youth, he yelled, “You will return to your vehicle, sir, and remain there!” The young man, stunned, stumbled and almost fell as he double-timed it back to the bike.

Powell returned to the car but this time left the door open and one jackbooted leg outside for emphasis. The few times he'd had to use this maneuver before, he'd enjoyed it: the rush of adrenaline (after all, an individual approaching the car from behind could be dangerous), the outsized and theatrical quality of it, the legally sanctioned bullying it involved. This time he noted that the young man was taller than he and though still lanky, he had begun to fill out; that, and the startled fear on the young man's face at Powell's sudden ferocity, had instead disturbed him and he felt a momentary regret at the way the whole interaction was unfolding.

Â

It had been the third time Powell spent the night at her place that Didi told him that she had known Franklin. They were lying in her bed, awake in the dark, the headlights of passing cars making the bright ghost of the window slide across the ceiling and down the wall.

“I didn't want to tell you right away. Because.”

“Because?” But what Powell was thinking was that she was a school shrink and she had known Franklin and here she was dating him so he couldn't have been the dad from hell who drove his kid right over the edge, right?

“Well, lots of reasons, I guess. I didn't want you to think I was feeling sorry for you. Of course I was. Feeling sorry for you. But not just that.”

“What, then?”

“Oh, Darlin', I don't know! I was drawn to you. Not everything can be explained.”

“Ah! I like that. âNot everything can be explained.' May I quote you?”

“What is with you, tonight?”

“I don't know.” Powell had now heard two things that made him feel better than he had in a while. He thought he should probably quit while he was ahead. “Go on,” he said.

“I don't know, I said. I liked your dignity. Your resilience.”

“And all along I was thinking you just wanted to get in my pants.”

“We call that projecting, Darlin'.”

“I just called it hoping.”

She slapped at him affectionately.

“So did he ever, you know, talk to you? Franklin?”