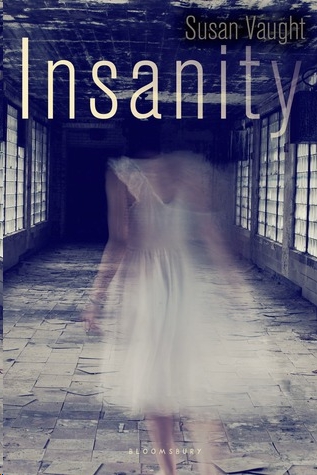

Insanity

Authors: Susan Vaught

For my sweet Frank, always and forever the best parrot ever.

I believe birds go to heaven, and you’re flying with the angels.

What hills, what hills, my own true love,

What hills so dark and low?

That is the hills of hell, my love,

Where you and I must go!

—“The Daemon Lover,” folk ballad, author unknown

Version recorded in Harlan County, Kentucky

Contents

Part III: The Scream at the End of the Hall

Levi

There was something wrong with the dog.

I saw it when I left the store, nothing but a little thing. I would have stopped to give it some love, but I had to get back before Imogene started to worry.

Don’t go out to night, boy. Death’s walkin’ on two legs.

But I had gone out, because I wanted some Slim Jims and peanuts and a Coke, and now I had a mutt following me home. It was a beagle with floppy ears and a tail that didn’t wag. Its eyes were too black, or maybe its teeth were too white.

I kept hold of my bag and walked faster, cutting in front of Lincoln Psychiatric Hospital. My breath made a fog. It was November and already cold in Never, Kentucky. Above the trees on my left, the old asylum’s bell tower hid the stars. It was dark, but the moon was bright, and I knew the way.

Behind me, that dog let out a growl.

Don’t look back. Something might be gaining on you.

Somebody famous said that, not Imogene. Maybe it was a

baseball player, but I couldn’t remember which one. Something flickered in the distance, winking between black pines and oaks.

Flashlight?

I glanced toward the psychiatric hospital. The back of my neck got the shivers, and that idiot dog growled again.

The bell tower. Had the light come from way up at the top? I slowed down, even though I knew I shouldn’t, and got a new case of the shivers.

Nothing good ever came from the top of that bell tower, or from any of the thin spots in that hospital. Imogene looked after the place as best she could, but sometimes—

“That’s about enough, Levi,” I told myself, mocking my grandmother’s voice. I shook my head to rattle out the stupid thoughts and headed for home again.

Something at the top of that tower turned with me. It was watching me. It was staring at my back, just like the dog was.

“Knock it off,” I muttered, and the mutt growled, and I walked so fast I was almost running.

My steps echoed on the path across the hospital grounds. Everything got quiet except the dog. It panted way too loud.

Light flashed across my face and I stumbled, blinking until I could see again, and then I stopped. The dog had gotten itself in front of me, its eyes wide and its mouth open and its tongue lolling to the ground. In that weird yellow light, its shadow rose across the trees behind it.

The shadow was giant and black and wolf-sized.

The shadow had red eyes.

Don’t go out to night, boy. Death’s walkin’ on two legs.

“You got four legs,” I told the creepy dog. I barely heard myself for the blood hammering in my ears.

Leaves crunched nearby.

I whipped around and fixed on the sound, expecting to see—what? A real wolf? Some crazy freak with a flashlight? Lincoln Psychiatric didn’t have murderers and bad criminals now. At least, I didn’t think they did.

Spots danced across my eyes as I squinted at the woods. Nothing. Just trees, and that old stone bell tower standing watch over Never. A single yellow light flickered way up at the top, like somebody was swinging an old-timey lantern.

I’m not crazy.

I puffed out more fog. I’d told myself that same thing a lot of times.

A twig snapped on my right, and I jumped again.

“It’s okay,” I told myself, watching the mist rise in front of my nose. The night smelled like wet leaves and grave dirt. “It’s just the dog.”

The beagle stood in that strange lantern light from the bell tower. It was wagging its tail, but that didn’t seem friendly. Its shadow still had red eyes, and the shadow wasn’t wagging its tail.

I backed away from the dog.

It followed me, pace for pace, its lips pulled back to show fangs as big as my fingers. The wolf shadow rippled across the trees, huge and black and bristly, and the tower watched like a menace at the edge of my thoughts. My breath came shorter and my blood pumped faster.

The hound opened its mouth and let out a howl so loud it rattled my skull. My feet tangled, and I fell backward against something warm and solid.

A man?

“Easy there,” said a voice deep enough to give me more shivers even as its owner kept me from spilling ass-over-teakettle and set me on my feet again.

“The dog—” I started to say but stopped, because I had Imogene’s blood and she had raised me to use it since my parents died, and people didn’t always see what I saw. If I asked him about his shadow, the man would think I was a runaway from the hospital. What was he doing here, anyway? Most people stayed off these paths.

“Sorry,” I said. “Just trying to get home.”

The man let me go, and then he laughed at me.

I didn’t like the sound.

The guy, he was tall and mostly bald, but muscled like a runner. His dark skin didn’t have any scars, and he was wearing suit pants and a nice shirt with a tie, but no jacket. Church clothes. He looked like a preacher.

“You’re one of them,” he said. “That’s too bad. But better now, before you’re old enough to make real trouble.”

The beagle snarled, and the man’s black eyes flicked to the dog. He muttered something I couldn’t hear, but I felt the power in every word. The mutt’s growl turned into a whine, and it shrank away and faded into the trees like a ghost.

Cold truth settled on my skin, and my teeth started to chatter.

That dog hadn’t been growling at me. It had been growling at

the preacher-man. Thunder rumbled from somewhere far away, and the light from the bell tower flashed before it went out.

Did the lunatics in Lincoln Psychiatric still run screaming through the halls when it stormed? I saw that on a news special one time. It used to be that way a hundred years ago. Imogene said so, and my grandmother always told the truth.

Run

, her voice whispered in my brain, but it was too late.

The man moved when I did, grabbing me and yanking me backward. My bag went flying as I crashed to the hard-packed ground of the path, spilling peanuts and Slim Jims all over the ground. Agony tore up my right arm as my bone snapped at the elbow. It hurt so bad I went dizzy and dumb. My face bashed against pebbles, and one of my teeth broke.

My thoughts knotted up and I yelled, but I didn’t hear anything because my throat didn’t work. I used my good arm to push myself up, but the preacher-man threw smelly powder in my face.

I coughed.

It burned. I couldn’t breathe.

Was the preacher-man saying a prayer? He rambled on about forgiveness and duties and saving souls. The guy was nuts.

It’s okay. I’m still breathing. I’m still alive

.

I blinked up at the man, who had daggers in his big hands.

I’m still alive

.

I told myself again.

And then, I wasn’t.

Forest

Her face reminded me of black marble, carved with wrinkles and frowns and sad eyes, always looking far away like she could see things I’d never understand.

Her hands—now those were cypress roots, dark and knobby, and rough when I had to touch them.

She never let go of the picture.

The photo was older than me, and she talked to it as though it were a person, down low where nobody could hear. It was laminated, and when I bathed her I’d wrap it in a plastic bag, because take that picture away from Miss Sally Greenway and she’d be throwing everything on the ward straight at your head. I never really looked at the photo, because I was too busy to pay it much mind.

How stupid was that? Stupid and wrong. That picture was the most important thing to the eighty-seven-year-old woman I dressed and fed almost every day. I should have looked at it.

When I finally did, I almost lost my mind.

“Be careful, Forest!” Leslie Hyatt slapped my hand so hard I almost dropped the comb I was trying to wedge into Miss Sally’s stubborn white hair.

Leslie’s dark eyes narrowed, doubling the wrinkles on her forehead. When she lifted her arm to point her finger at me, her oversized black scrubs fanned out until she looked like a giant bat. “What if she was your grandmama, girl? Would you want her hair pulled by some fool teenager can’t make a braid without yanking the poor woman bald?”

She stepped toward Miss Sally, who sat in her wheelchair without moving or speaking, holding that black-and-white picture of a man she hadn’t seen since she was young. “Give me that.” Leslie took the comb away from me. “I done told you, it’s like this.”

She worked the teeth of the comb, gently teasing smaller and smaller sections of hair. For her, they stayed right where she put them.

I fiddled with the rowan-wood bracelet on my right wrist, running my fingers across its familiar carved surface and smooth iron beads. “Sorry.” I managed a smile despite my stinging knuckles. I liked Leslie. She’d been helping me learn since I first came to work on second shift at Lincoln Psychiatric Hospital.

That was six months ago—two days after I turned eighteen, aged out of foster care, and had to take my GED and find a place to live. When I wasn’t pulling hair, I was bottom-of-the-line staff at Lincoln, nothing but a bath-giver, a bed-pan scrubber, a bed-changer. I clipped fungusy nails, changed stinky clothes and disgusting diapers, made beds, fed patients, got spit on and bit and kicked and called names—whatever it took to keep nineteen elderly folks clean and comfortable in a forgotten basement ward in a double-forgotten state psychiatric hospital. If it paid me a salary and provided insurance and earned me overtime privileges so I could make more money, I’d do it, and I’d smile and mean it. Every dollar I got to put into savings instead of spending on rent and food was a dollar toward getting to college—and getting out of Never, Kentucky.

While Leslie worked on Miss Sally’s hair, something rumbled outside the cedar-colored limestone walls. It came on slow and quiet, but it built and built and

built

until the barred windows rattled and the fluorescent lights flickered. All along the single hallway of Lincoln’s geriatric ward, patients grumbled or whimpered or shifted in their wheelchairs. A few started rolling toward their rooms.