Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation (39 page)

Read Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation Online

Authors: Elizabeth Pisani

Map J: S

UMATRA

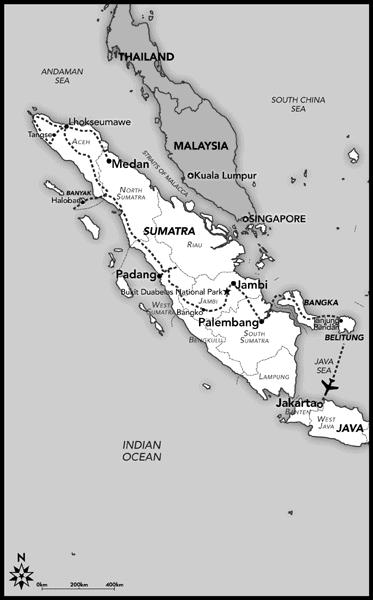

Aceh, indeed all of Sumatra, proved quite different from the parts of eastern Indonesia that I had been drifting around in the previous months. Sumatra is vast, so vast that if you smushed all 4,100 islands of NTT, Maluku, North Maluku and the Sangihe chains together, they’d only take up a quarter of the area of that single western Indonesian island. A forested mountain range wells up in Aceh in the northern tip of the island, then runs for 1,600 kilometres down the west coast. On the eastern side of the range, the rainforest tumbles down onto flatter land, then peters out, leaving a huge marshy plain criss-crossed with rivers; that’s what makes is such good plantation country.

It’s culturally diverse too. The Acehnese, sitting on the ‘Veranda of Mecca’, pride themselves on being more Islamic than anyone else in Indonesia. Just to the south of Aceh, around the huge upland Lake Toba, Christian Bataks are as clannish as any ethnic group in Indonesia; their enthusiasm for funerals and other sacrificial festivals rivals that of Sumba. The Minangkabau of West Sumatra are proud Muslims and energetic intellectuals as well as purveyors of the nasi Padang dishes that unify the nation. On the east coast, the traders of Palembang, also staunchly Islamic, take plain speaking to levels unknown in mealy-mouthed Java. And that’s just four of Sumatra’s dozens of tribes.

The bus journeys from Medan and around Aceh had surprised me not just because they passed through thickets of posters proposing former rebels for governor. On the first trip, from Medan up to Langsa, I had bought a numbered ticket for a bus that was scheduled to leave at a fixed time. It seemed an odd concept – in eastern Indonesia the scheduled departure time was ‘whenever the bus is full enough’. But from Medan we had left at the appointed time, with me comfortably ensconced in my appointed seat.

Not a kilometre out of the bus station, the driver screeched to a halt to pick up someone who was standing on the roadside, flapping their hand. Then another, and another. At each impromptu stop the driver’s assistant would scoop the new passenger into the back door and a friend would pass up sacks of rice and baskets of chickens. One early addition to the passenger list smiled at me. ‘Excuse me, you don’t mind if I . . .’ I quickly averted my eyes but it was too late. Now there were three of us in two seats. Another few kilometres, another few dozen stops, more smiling and I’m so sorries, and we were three and a half, the newcomer balanced between the seat edge and a pile of cement bags.

For a nation that is so much on the move, Indonesians are rotten travellers. On boats they get seasick (

mabuk

– ‘drunk’) before I can even tell that we’ve left the dock. And on buses, every second passenger seems to clutch a little bottle of

balsem

under their nose.

Balsem

, a cure-all that smells like a mint julep infused with Vicks VapoRub, is supposed to settle the stomach. It is a sure sign that vomiting will ensue. The woman who had squeezed herself into my numbered seat early on that first fourteen-hour bus journey from Medan duly began sniffing balsem, then retching quietly into a plastic bag. The sound was drowned out by the dangdut music that pounded from the speakers positioned every two metres along the length of the bus.

The alternative to the long-distance buses is to take a series of short-hop minibuses (in northern Sumatra they’re called ‘L300s’ after the Mitsubishi model that most drivers use). These stop even more frequently for flapping hands, and take long detours to drop someone at home or to pick up a package from Auntie’s house. Designed for eleven passengers, they often squeeze in as many as eighteen. That makes it a good idea to wheedle a seat up in front, with the driver. Sitting up front has lots of advantages beyond actually being able to see anything other than the back of someone’s diamanté-studded jilbab. Because drivers like to protect their own space, they rarely put more than two other people in the passenger seat. Drivers know their area well, and are often chatty and informative, providing recommendations and sometimes door-to-door delivery to a friendly guest house. Being up front puts you in reach of the stereo system; I became adept at turning down the volume with my elbows while pretending to rummage in my bag. Sometimes, the driver would let me plug in my USB stick and play my own music for a while; from passenger feedback I soon learned that I could get away with Lyle Lovett and k.d. lang but not with flamenco or anything classical.

Watching the drivers was fun, too. I started giving out mental prizes for multitasking. On a one-lane road that snaked from blind corner to hairpin bend, I watched one driver light a cigarette. Then, with it hanging from his mouth, he peeled a

salak

. A salak is a teardrop-shaped fruit, white and waxy inside, covered in crispy brown snakeskin, fiddly to peel. He steered us around the hairpins with his forearms as he attacked this task, chatting all the while, steering just with his right elbow when he needed his left hand to change gear, flick the ash from his cigarette or answer his phone.

I was flapping my hand on the roadside just north of Lhokseumawe on the east coast of Aceh one afternoon, when an L300 screeched to a halt. I asked the driver – a handsome man in his mid-fifties with a clipped moustache – whether he could drop me in Sigli. He waved me into the front seat, and introduced himself as Teungku Haji. That confused me: Teungku is an Acehnese honorific accorded to people who are considered to have a lot of Islamic learning, while Haji is an honorific used for a person who has made the pilgrimage to Mecca. It was like calling yourself Sir Reverend. Over his short-back-and-sides haircut, Teungku Haji wore a white Islamic cap, embroidered in gold. He chatted cheerfully about the usual things, the incompetence of the government, the elections, the prospect of higher fuel prices. He fed me salted fried banana crisps. ‘You’re too skinny.’ Eventually, he asked what business I had in the uninspiring coastal town of Sigli.

Actually, I said, I just wanted to change buses there, to head inland to the tiny mountain village of Tangse – this was when I was hoping to reconnect with Asya, the NGO worker I had met two decades before. ‘It is the will of God that we met!’ declared Teungku Haji. Of the hundreds of daily buses that pass where I had flagged him down, his was one of only two that go to Tangse. As we turned off the main road and headed west through rice fields, the clouds that hung over the mountains of central Aceh flamed orange and the evening call to prayer echoed from mosques up and down the valley. By the time we drove into Tangse, the mountains had turned to dusty purple and one or two stars embroidered the sky. Teungku Haji asked where I planned to stay. I asked which guest house he’d recommend. ‘Guest house? There are no guest houses in Tangse.’

Pause.

‘Why don’t you come home with me?’

Pause.

I didn’t want to be rude. But ‘just say yes’ doesn’t necessarily extend to accepting invitations issued at dusk to stay overnight with a bus driver in an isolated village, Islamic prayer cap or not.

I tried to extricate myself. ‘That’s such a kind offer. Really. But I think it’s not necessary. Please drop me at the NGO mess.’ I was sure I’d recognize the Save the Children house where I had stayed all those years before. But the driver had no idea what I was talking about. ‘There’s no NGO in Tangse.’

And then again: ‘Come home with me.’

He looked over at me, and I quickly averted my eyes. Then Teungku Haji burst out laughing and slapped the steering wheel with glee. ‘Aduh! I don’t mean like

that

, Ibu.’ He explained that he was an outsider in Tangse, from Bireuen on the coast, but that his wife was Tangse born and bred. ‘You come home with me, she’ll know what to do.’

Ibu Hamidah knew exactly what to do. She unrolled two carpets on the living room floor and spread my sleeping mat on top of them. ‘There. Your bed.’ The carpets had been on loan to the local mosque for a visit by the current Governor of Aceh, Irwandi Yusuf, and had just come back from the cleaners that day. ‘You see,’ said Ibu Hamidah. ‘It is the will of God that you should stay with us.’

That’s how I made friends with Yufrida. Yufrida is Hamidah’s daughter (and Teungku Haji’s stepdaughter; it’s the second marriage for both of them). When we arrived, she was sitting in the front room in a red wheelchair. I was introduced to Hamidah, and to Hamidah’s parents – her father a tall, dignified man with vaguely Arab features, her mother’s pudding face slashed by a betel-stained mouth and narrow, distrustful eyes. But I wasn’t introduced to Yufrida.

I said hello to her myself, and she greeted me in response, slurred, but comprehensible enough. Yufrida has extraordinarily twinkly eyes and a light-up, buck-toothed smile.

‘Don’t bother with her,’ said Pudding Faced Grandma. ‘She’s a cripple. Go on, give us some money.’ Just like that.

Yufrida sat in her wheelchair, her feet corkscrewed in towards each other, her right arm held rigid in front of her body, her left hand bent upwards in a hook at her side. She said nothing. Now Hamidah introduced her properly. ‘This is Yufrida,’ and she ruffled her hair affectionately. Hamidah treated her daughter with great kindness. But still she complained, in front of Yufrida, how exhausting it was to care for a thirty-year-old daughter who had been disabled since childhood, to spoon-feed her, to bathe her, to heave her on and off the toilet.

I rather ignored Yufrida for the rest of the evening. Most of the time, she sat quietly in her chair. When she did speak, I could make little sense of it, and from the way everyone but her mother ignored her, I assumed she was talking nonsense, though I realized later she was speaking Acehnese.

The following day, I went to plant cocoa seedlings with Ibu Hamidah and her father. At the age of eighty-three, with a fifty-kilo sack of fertilizer hefted onto his shoulders, he strode across the fields so fast that it was hard to keep up. When we came back, Yufrida greeted us joyously. When her cousins from further up the village dropped in to say hello, she engaged with them as much as their awkwardness with her allowed. I realized that Yufrida’s mind was in perfect working order. I just hadn’t made much effort to understand her.

In the evening, I said I thought I’d wander along and visit the cousins, and invited Yufrida to come with me. She was thrilled, but Granny was horrified. ‘You mustn’t!’ she waved her hands at me, as if to make me disappear in a puff of witchcraft. ‘She never goes out. It would be too shameful.’ I asked Yufrida if she would be ashamed to come for a walk with me. She shook her head vigorously. ‘

Tidak

!

’ No! Clear, emphatic. Hamidah smiled: ‘Well if you’re going visiting, you’ll want to look your best.’ And she helped her daughter into clean clothes, brushed her hair, and dabbed on face powder and lipstick, until I felt quite dowdy by comparison.

We must have made an odd pair, this unknown Caucasian woman, leathery with travel, a badly tied jilbab slipping off every few minutes to reveal shorn hair, swearing and apologizing as she pushed the wheelchair over the lumpy stone road. In the chair the younger Acehnese woman with alabaster skin, not just uncomplaining but grinning as she was lurched from bump to bump. Later, her mother took me aside and explained that I needed to tilt the chair back on its rear wheels when coming up to a difficult patch. ‘Yufrida asked me to explain. She thought she might hurt your feelings if she told you herself.’

People stared at us as we passed, but when we yelled out our good evenings, me in Indonesian, Yufrida in Acehnese, they responded. By our third evening walk, the villagers were greeting us as soon as we lurched into sight.

The next day, Ibu Hamidah and I set off on her motorbike; we drove the forty kilometres or so up the river valley to Geumpang. In theory we were trying to find informal gold miners – I’d heard there were many of them panning in this area – but as much as anything we were just going for a girls’ day out. It was a glorious day, clear and slightly blustery. As we climbed beyond the rice fields that lined the river plain around Tangse the valley closed in on itself. An energetic river churned over grey boulders on the valley floor, carving a gorge between the road and a cliff of rock on one side and a steep wall dressed in tumbling green vines on the other. We passed a collapsed suspension bridge that now consisted of two wires strung high above the gorge. Balanced mid-air on the bottom wire and clinging to the top one for safety were a middle-school girl with a knapsack of books on her back, a boy in the maroon and white uniform of primary school, and two young mothers with babies strapped to their backs.

In a restaurant built out over the gorge, we stopped for a coffee. We gossiped and laughed about this and that. Like her daughter, Hamidah had a beautiful, open smile; her eyes twinkled with fun behind little oval glasses. She was confident and assertive, without being bossy. ‘Are you sure you want to go out without your jilbab?’ she’d ask, if I made for the door having forgotten to cover my head. ‘Just saying . . .’