Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation (27 page)

Read Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation Online

Authors: Elizabeth Pisani

In fact, the flights hadn’t exactly been cancelled. They had just lapsed. Flights to Banda are subsidized, chartered by a provincial government which hopes to curry favour with voters by providing cheap transport between districts. The government renews the tender for these charter flights every six months; it doesn’t invite new applications until the previous contract has run its course. So twice a year, there’s a period of several weeks where there are no flights. One of those gaps always falls in late December and early January: peak tourist season.

Inevitably, some islanders believe this is a plot by Ambon to undermine tourism in Banda. ‘The government in Ambon is jealous of us,’ said a woman who owns a guest house and has her finger in several other tourism-related pies. ‘They hate that tourists just stay in Ambon for a day before heading to Banda for a week.’

When I asked the airline agent whether he thought the interruptions in service were deliberate, he laughed at the idea. ‘That would be too complicated,’ he said. So why don’t they start the tender process six weeks earlier? I asked. ‘That’s the bureaucracy in this beloved country of ours. It’s just how it is.’

Begitulah

.

*

Wallace,

The Malay Archipelago

, Vol. 2, Chapter XXIX.

*

Wallace,

The Malay Archipelago

, Vol. 2, Chapter XL.

*

Sophisticated studies by Western academics seem to confirm this folk wisdom. One fascinating study of illegal logging uses satellite imagery to show that in the forested provinces of Sumatra, Kalimantan and Papua, the creation of a sub-district leads to an 8 per cent jump in tree felling, on average. This is true even in the areas where no new logging is allowed under national law. See Burgess et al., 2012. Meanwhile, spending on local roads doubled a year after budgets were handed to the districts, then doubled again in the year after the first direct elections for Bupati; government inspections show the quality of the roads fell despite a seven-fold increase in spending in the decade to 2010.

*

In the 2004 elections in South Sulawesi, eleven of the thirteen provincial parliamentarians who had previously been convicted of corruption were re-elected.

*

This excludes the 465,000 members of the armed forces and 412,000 cops.

*

Wallace,

The Malay Archipelago

, Vol. 1, Ch. XIX.

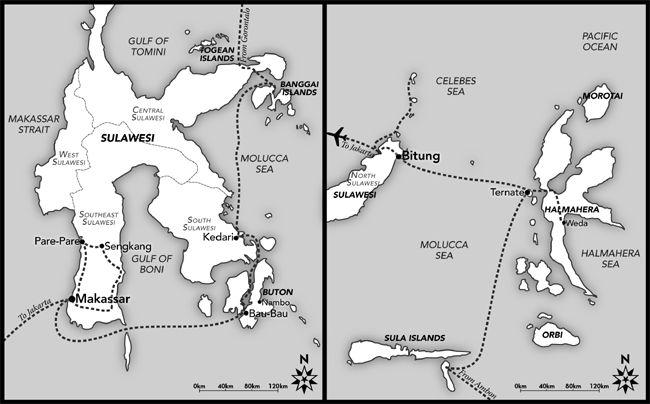

Map F: S

OUTHERN

S

ULAWESI

, Showing Buton Island

Map G: H

ALMAHERA

, North Maluku

Daylight comes quickly to the tropics. Arriving before dawn in Ternate, the capital of North Maluku, I sat at a street stall waiting for it to get light. One minute I could see no further than my flowered glass of grainy coffee, the next, I was looking at the grey velvet outline of Mount Gamalama, the volcano which makes up most of Ternate. A few moments more and velvet solidified into hard-edged green. The platinum disc of the sun soared up from behind the mountain and the city, which patterns the south-eastern skirt of the volcano, sprang to life.

Gamalama is both the source of Ternate’s wealth – its clove crop – and of its repeated destruction. Just over a month before I arrived in January 2012, the volcano had started coughing out great clouds of ash. A few weeks later heavy rains turned the thick blanket of ash on the upper slopes of Gamalama into a river of black mud. The cold lava oozed down the mountain, gathering force and boulders, some of them four metres across. By the time it was on the lower slopes, it bulldozed everything in its path. ‘Everything’ included around eighty houses and three lives.

I went to have a look at the area that had been worst hit. I found a man shovelling gravelly mud out of a house that had lost its windows, but appeared otherwise intact. His wife invited me in, apologizing because she couldn’t offer me a cup of tea. The lava may have entered politely enough through doors and windows, but it had been less gentlemanly as it left, gashing through the peach-plastered back wall, leaving a three-sided room a bit like an architect’s model, but muddier.

This area has always been designated high risk, and construction of houses is forbidden. But flattish land is at a premium in Ternate, so people build anyway. The woman hoped that the government would now resettle her family somewhere safer.

While waiting for a new plot, this family was living down in the local technical training centre. When the mud-flows started there were 4,000 refugees crushed into the centre; as the threat of more lava receded and the army bulldozed the mud out of the surviving houses, most drifted home. By the time I visited, around 300 people were still scattered around the training centre. They had divvied up the assembly hall, marked out territory with towers of cardboard boxes, children’s bicycles, raffia strings of school uniforms, the forlorn remnants of a life before the all-embracing mud. People seemed remarkably resigned to their temporary fates, however, and for the kids, who had access to the swings and seesaws of the neighbouring kindergarten playground, it was an adventure.

It sounded as though there was a bit of a party going on out the back. I followed the sound of the music and found an olive canvas

M*A*S*H

tent: the communal kitchen. A volunteer trained in disaster preparedness used a stainless-steel garden shovel to dole rice from a waist-high cooking drum into family rice-bowls. Other volunteers plopped a few pieces of fried fish from a plastic laundry tub and a spoonful from a vat of soupy greens on top of the rice.

When the feeding was over, the music was cranked up and the kitchen turned into a temporary disco. People, mostly men, started dancing that bent-kneed, bum-jutting, twirly wristed dance that goes so well with

dangdut

music. Dangdut is an Indonesian pop music which combines vaguely Indian melodies with the dang-

dut

dang-

dut

beat of conical

gendang

drums, a sort of Bollywood–House Music mash-up.

Someone arrived with a clutch of durian. The dance floor cleared as everyone fell on the fruit, splitting open the spiky oversized hand grenades to reveal the pale yellow smush inside. You’re not allowed to carry durian on planes in Indonesia, or take them into posh hotels, because their methane smell oozes through the air-conditioning system into every corner. It’s an acquired taste that I’ve never acquired, less because of the stick-to-the-back-of-your-throat taste than because of the stick-to-the-roof-of-your-mouth texture: creamy, oily and sticky all at the same time. But now people were competing to offer me the most luscious gobs of this aphrodisiac: ‘Here, here. Eat mine! Mine’s sweeter than his!’ There’s always a lot of

double-entendre

in durian-speak.

There was a palpable sense of good-natured camaraderie among the volunteers. But when the supervisor was giving me a lift home, he looked up at the thunderclouds that had closed ranks around the top of the volcano and shook his head grimly: ‘That’s a big storm up there,’ he said. ‘Tomorrow, we cook for more refugees.’

Yes, the volcanoes destroy things. But the ash they cough out also makes these islands some of the most fertile on the planet. Indonesia strings together 127 active volcanoes; down one side of Sumatra, the giant island that guards Indonesia’s western flank, and along the whole spine of neighbouring Java, volcanoes spur rice fields to extraordinary bounty. Many farmers manage three rice crops a year, against just one in less fertile regions, and they produce an abundance of fruit and vegetables too. The fire-mountains bypass Borneo, taking the southern route and sweeping up in a great arc through the hundreds of small islands that make up Maluku, and pimpling the northern tip of Sulawesi as well. It is in these eastern regions, and especially in the smaller islands such as the Bandas and Ternate where sea breezes waft constantly over the volcanoes’ slopes, that the ash gives life to spices.

The vulcanology services can afford to monitor around half of the mountains that are currently active. Occasionally a big eruption wakes up some of the dozens that are sleeping. Mount Sinabung in Sumatra, which has been snoozing since at least 1881, for example, suddenly came back to life in 2010. This Sleeping Beauty effect was probably a slow reaction to the kiss of an under-sea eruption six years earlier. That eruption led to the tsunami on Boxing Day, 2004, that killed 170,000 Indonesians, mostly in Aceh, and that marks lives and behaviour to this day.

I was in the highlands of Aceh in April 2012 when my phone started beeping madly, the messages coming in from Jakarta, Sumba, even more distant Papua. ‘Where are you?’ ‘Are you OK?’ I was in a minibus, clipping along over bumpy mountain roads on the way to Takengon, wondering why everyone was standing out in the street. ‘Massive earthquake in Aceh. Tsunami predicted in 20 minutes.’ That message was from Singapore.

In twenty minutes I was in the lobby of a quasi-posh hotel in Takengon where guests, staff and people like me who had come in off the street were all glued to the TV. The live coverage spoke of an earthquake measuring 8.6 on the Richter scale. In Banda Aceh, the coastal capital of Aceh that had only recently rebuilt itself from the devastation of 2004, people were screaming and running, getting on their bikes, in their cars, making for higher ground. As we watched the panic down on the coast, the kitsch chandelier in the mirrored ceiling above us started to tremble, then really shake. Everyone went deathly silent for a long moment; we looked at one another, as if waiting for leadership. Then someone said ‘Here we go again!’ and we all quick-stepped out into the rain.

That second quake was even bigger than the one of half an hour earlier. My teeth rattled along with the windows of the hotel, and the pit of my stomach began to thrum. The hotel receptionist had seized on to me. She gripped my arm until my hand went numb. By the time the chandelier stopped its tinkling, we were soaked through. The vibrations in my belly continued for quite a while, and there was no let-up on my arm. The receptionist was utterly undone by the quake; all the blood had drained from her face and her knees were weak, but she wouldn’t sit down because then she’d feel the shaking all the more. She didn’t want to go back inside and get out of the cold mountain rain. ‘Trauma,’ she kept whispering. Just that one word: ‘Trauma.’ Later, she told me that her mother, a brother and two sisters had been swept away in 2004. She had moved to the highlands to climb away from her memory, to silence the idea that buzzed like a mosquito in a darkened bedroom: it could happen again, it could happen to you.

People who have moved to a city, who live under a watertight roof, who control their body temperature with air-conditioning, can easily zone out the threatening downside of the nation’s geography, which can wipe out your present and change your future in a few minutes. But many millions of Indonesians still pass each day in the knowledge that they are at the mercy of this unstable land.

Mother Indonesia can be menacing, certainly, but she is also extraordinarily bountiful. ‘The people of Maluku got spoiled because spice trees made us rich with very little effort, there’s lots of land, the sea is full of fish,’ Edith, a maths professor in Ambon, the capital of Maluku, had told me.

I’m never sure whether Indonesians know how unfashionable they are being when they trace human behaviours to climate and the wealth of the land and sea, particularly if those behaviours are laziness, profligacy, a failure to plan ahead. But they do it all the time. Maybe it is only unfashionable in the world of ‘development’, where (mostly white, cold-climate) people earn good salaries trying to atone for the sins their forefathers have visited on (mostly brown, warm-climate) people. The ‘generous earth makes people lazy’ argument seems to tar people in warm latitudes with a single, undesirable brush simply because of where they were born; akin to racism, almost. But from Indonesian mouths, ‘

Kami di manja bumi

’, ‘Mother Earth has spoiled us’, is something I heard over and over.