Indian Captive (3 page)

Come What May

“M

OLLY CHILD, NOW SUPPER’S DONE

, go fetch Neighbor Dixon’s horse.”

Molly looked up at her father. At the far end of the long table he stood. He was lean, lanky and raw-boned. Great knotty fists hung at the ends of his long, thin arms. His eyes looked kind though his face was stern.

“All I need is another horse for a day or two,” the man went on. “Neighbor Dixon said I could borrow his. I’ll get that south field plowed tomorrow and seeded to corn.”

“Yes, Pa!” answered Molly. She reached for a piece of corn-pone from the plate. She munched it contentedly. How good it tasted!

Corn! All their life was bound up with corn. Corn and work. Work to grow the corn, to protect it and care for it, to fight for it, to harvest it and stow it away at last for winter’s food. So it was always, so it would be always to the end of time. How could they live without corn?

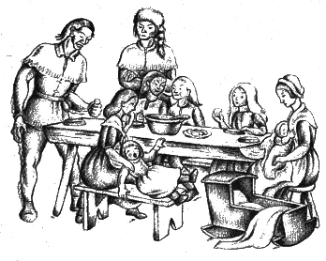

The Jemison family sat around the supper table. Its rough-hewn slabs, uncovered by cloth, shone soft-worn and shiny clean. A large earthen bowl, but a short time before filled with boiled and cut-up meat, sat empty in the center. Beside it, a plate with the leftover pieces of corn-pone.

“You hear me?” asked Thomas Jemison again. “You ain’t dreamin’?”

The two older boys, John and Tom, threw meaningful looks at their sister, but said no word. Betsey, tall, slender fifteen-year-old, glanced sideways at their mother.

Molly colored slightly and came swiftly back from dreaming. “Yes, Pa!” she said, obediently. She reached for another piece of corn-pone.

Inside, she felt a deep content. Spring was here again. The sun-warmed, plowed earth would feel good to her bare feet. She saw round, pale yellow grains of seed-corn dropping from her hand into the furrow. She saw her long, thin arms waving to keep the crows and blackbirds off—the fight had begun. The wind blew her long loose hair about her face and the warm sun kissed her cheeks. Spring had come again.

“Can’t one of the boys go?” asked Mrs. Jemison. “Dark’s a-comin’ on and the trail’s through the woods…”

“Have ye forgot the chores?” Thomas Jemison turned to his wife and spoke fretfully. “There’s the stock wants tendin’—they need fodder to chomp on through the night. And the milkin’ not even started. Sun’s got nigh two hours to go ’fore dark. Reckon that’s time enough for a gal to go a mile and back.”

“But it’s the woods trail…” began Mrs. Jemison anxiously. “’Tain’t safe at night-time…”

“Then she can sleep to Dixon’s and be back by sunup,” said the girl’s father, glancing sternly in Molly’s direction. He sat down on a stool before the fireplace and began to shell corn into the wooden dye-tub.

“Mary Jemison, do you hear me?” he thundered.

“Yes, Pa!” said Molly again. But she did not move. She sat still, munching corn-pone.

Jane Jemison said no more. Instead, she looked down at her hands folded in her lap. Her hands so seldom at rest. She was a small, tired-looking woman, baffled by both work and worry. Eight years of life in a frontier settlement in eastern Pennsylvania had taken away her fresh youth and had aged her beyond her years.

Little Matthew, a boy of three, climbed into his mother’s lap. She caught the brown head close to her breast for a moment, then put him hastily down as a wailing cry came to her ears. The baby in the homemade cradle beside her had wakened. The woman stopped wearily, picked him up, then sat down to nurse him.

“Ye’ll have to wash up, Betsey,” she said.

Molly’s thought had traveled far, but she hadn’t herself had time to move. She was still sitting bolt upright on the three-legged stool when her ears picked up the roll of a horse’s hoofs.

Nor was she the only one. The others heard, too. As if in answer to an expected signal, the faces turned inquiring and all eyes found the door. All ears strained for a call of greeting, but none came. In less time than it takes for three words to be said, the door burst open and a man stumbled in.

It was Neighbor Wheelock. He was short and heavy. Like Thomas Jemison, he too had the knotty look of a hard worker, of a frontier fighter. It was only in his face that weakness showed.

Wheelock gave no glance at woman or children. He said in a low but distinct voice to Thomas: “You heard what’s happened?”

The clatter of a falling stool shook the silence and a cry of fear escaped. Betsey, white-faced and thin, clapped her hands over her mouth. Mrs. Jemison, the nursing baby still at her breast, stood up. “Let’s hear what ’tis,” she said, calmly.

Chet Wheelock needed no invitation to speak. The words popped out of his mouth like bullets from a loaded gun.

“It’s the Injuns again!” he cried, fiercely. “They’ve burnt Ned Haskins out and took his wife and children captive. They’ve murdered the whole Johnson family. They’re a-headin’ down Conewago Creek towards Sharp’s Run, a-killin’, a-butcherin’ and a-plunderin’ as they come. There ain’t a safe spot this side of Philadelphy. I’m headin’ back east and I’m takin’ my brother Jonas’s family with me.”

Thomas Jemison looked up from his corn shelling, but his placid face gave no hint of troubled thoughts. A gust of wind nipped round the house and blew the thick plank door shut with a bang. The children stared, wide-eyed. Jane Jemison sat down on a stool, as if the load of her baby had grown too heavy and there was no more strength left in her arms.

“What are we a-goin’ to do, Thomas?” she asked, weakly.

“Do?” cried Thomas. “Why, plant our corn, I reckon.”

“You won’t be needin’ corn, neighbor.” Chet Wheelock spoke slowly, then he added, his eyes full serious: “You ain’t aimin’ to come along with us then?”

Thomas Jemison rose to his feet. He thumped his big doubled-up fist on the table—his heavy fist that looked like a gnarled knot in an old oak tree. “We’re stayin’ right here!” he said.

“But, Thomas, if Chet says the Indians’re headin’ this way…” began Jane.

Thomas stood up, tall and gaunt. He laughed loudly.

“I ain’t afeard of Injuns!” he cried. “I’ve lived here for eight years and I ain’t been molested yet. There’s been Injuns in these parts ever since we first set foot in this clearing. We’ve heard tell of so many raids, so much plunderin’—I don’t put much stock in them tales. No…I don’t give up easy, not me!”

John and Tom, the two boys, laughed too. “Who’s afeard of Injuns? Let ’em come!” they cried in boastful tones.

Jane put the baby down quickly in its cradle. She caught her husband desperately by the arm.

“Don’t you hear, Thomas? Chet says they’ve murdered the whole Johnson family…We can’t live here with Indians on all sides…devourin’ the settlement. Forget the corn.

“We’re stayin’ here, I said!” repeated Thomas. “Come what may, I’ll plant my corn tomorrow!” His voice rang hard, like the blow of a blacksmith’s hammer against the anvil.

In the silence that followed, Jane’s hand fell from her husband’s arm. Molly ran to her mother’s side and put both arms about her waist.

Thomas’s voice went on: “As soon as the troops start operations, the Injuns’ll run fast enough. They’ll agree to a treaty of peace mighty quick. Then our troubles will all be over. We’ve stuck it out this long, we may as well stay for another season. Leave a good farm like this? Not yet I won’t! I’ll plant my corn tomorrow!” His words were cocksure and defiant, but they brought no comfort to his listeners.

The baby began to cry and Neighbor Wheelock went out. In a moment he was back, addressing Mrs. Jemison.

“I brought my sister-in-law and her three children along with me, ma’am. Her husband, my brother Jonas, is with the troops and I’m takin’ her back east. She won’t stay in the settlement longer. Our horse was half-sick before we started and can’t go no farther. Can ye give us lodgin’, ma’am, for a day or two, to git rested up?”

None of the Jemison family had looked out or seen the woman. She stood by the horse, waiting patiently, with a boy of nine beside her and two small girls in her arms. Mrs. Jemison hurried out to bid her welcome, calling back to Betsey to put the pot on to boil.

“Boys, the chores!” called Thomas. Then he added, “Go fetch Neighbor Dixon’s horse, Molly-child, like I told you.

Molly and her father walked out the door together. Despite his stern ways and blustering words, he had a great affection for his children and Molly was his favorite. He put his great, knotty hand on her head and rumpled her tousled yellow hair.

“Pa…” Molly hesitated, then went on: “Ain’t you ever afeard like Ma?”

“Why should I be afeard?” laughed her father. “There’s nothin’ to be scared of. The Injuns’ll never hurt

you

, Molly-child! Why, if they ever saw your pretty yaller hair, a-shinin’ in the sun, they’d think ’twas only a corn-stalk in tassel and they’d pass you by for certain!”

Molly laughed. Then she turned her head and looked back—in through the open cabin door. She saw her mother and Betsey with Mrs. Wheelock and her little ones busying themselves in the big room. She saw the thick oak timber door, battened and sturdy. She knew it turned on stout, wooden hinges and was secured each night with heavy bars, braced with timbers from the floor. She wondered if, even then, it was strong enough to keep the Indians—the hated, wicked, dangerous Indians out.

Her blue jeans gown flew out behind her, as past the barnyard, on long, thin legs she ran. She passed Old Barney, her father’s horse that had the devil in him and liked to kick, making a circle wide of his heels. She passed the grindstone and the well-sweep with the grape-vine rope. Then she ran the full length of the rail fence that bordered the field where the corn would soon be growing and rustling in the breeze. She flew past the bee-tree where, the autumn before, her brothers had caught the bear, his claws all sticky with honey.

Molly Jemison was small for her age. She looked more like a girl often than the twelve she really was. Her blue eyes shone bright from her sun-tanned skin and her hair was yellow—the pale, silvery yellow of ripened corn. She ran swiftly, her whole body swinging to the free and joyous motion.

Molly was glad to go to Neighbor Dixon’s—anywhere, anywhere to get out of the house. There was always a load of anxiety there, reflected in her mother’s face and her father’s stern words. A load of worry which pressed down upon her naturally light spirits and brought sadness to her heart. This latest news of the Indians would only make things worse.

Then, too, there was always a fever of work in the house—so many things that had to be done. She wondered sometimes if her father and mother ever thought of anything else but work. It seemed to keep them busy from morn to night getting food and clothing for their large family. Had they no time for happiness?

Out-of-doors, Molly could get away from it all. She could forget there were such irksome duties as spinning and weaving, cooking and sewing; and worst of all doing sums and reading in books. Betsey could do these things. Betsey “took to them,” as their mother said. She did not bungle as Molly did.

But out-of-doors Molly could watch the birds, the butterflies, and all the wild things. She could be one with them. She could pretend she was as wild, as free, as happy as they. When she had work to do out-of-doors she worked willingly enough. She thought now of the happy days to come—working in the corn, plowing, planting, weeding…

Molly ran on. Soon she was in the woods. She knew every inch of the trail, each stone, each stump, each tree. She ran fast and reached the Dixons’ cabin before the slanting rays of the setting sun were blotted out by the trees.

“Tell her to make me a cambric shirt, Without any seam or needlework.

Tell her to wash it in yonder well,

Where never spring-water nor rain ever fell.

Tell her to dry it on yonder thorn,

Which never bore blossom since Adam was born.”

Molly’s voice, thin and piping, broke through the quiet of the forest. Her heart sang, too, as her lips formed the words. The song was an old one of her mother’s. Many songs her mother had used to sing. Why was it now she sang no more? Was it fear that had stopped her singing?

It was early the following morning and Molly was on her way back from the Dixons’. The sun had not yet risen. In the woods, the light was dim and uncertain—the early light before dawn. The morning air smelled clean and freshly washed. The birds were awake, chirping and singing. A gentle breeze stirred, rustling the branches of tender green.