Indian Captive (13 page)

But Red Bird did not lift her hand. She did not look at the bird on the handle of the new-carved ladle. She pointed to the door where, stood the baskets that in the morning had held seed-corn. She pointed to Corn Tassel’s bed, then she looked at the girl.

“When one has worked hard and is hungry,” she repeated in a quiet voice, “the succotash lies well on the tongue.”

Molly climbed into her bed, tearless. Well had she learned her lesson, a lesson she would not forget. She climbed into her bed without her supper. She had learned that from now on she must work if she would eat.

Slow Weaving

“A

BASKET FOR ME?”

A

SKED

Molly in surprise.

“When the corn is ripened for picking,” said Shining Star quietly, “you will see there are not baskets enough. It is always good to have one more. A basket is useful for many things—for gathering the fruits of the earth, for carrying loads, for storing supplies.”

Shining Star looked very beautiful this morning. Her blue skirt and bright red leggings were made of broadcloth and were richly embroidered with bead designs. Her figured calico over-dress was fastened down the front with a row of shining silver brooches. Above the colorful costume, silver earrings dangled from her ears and her face beamed with honest kindliness.

Putting her baby in Molly’s arms, she sat down under a shady tree beside the lodge. From the top of a pile of splints cut from the black ash tree, she picked up an unfinished basket and began to weave. The dry splints rattled pleasantly to the touch of her deft fingers.

“Today it will be finished,” said Shining Star, in her low, soft voice, “the basket for Corn Tassel.”

Molly’s eyes glowed with pleasure. “A basket of your making, my sister,” she answered shyly, “will please me very much.”

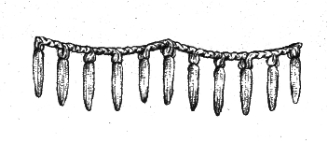

Molly made a new nest of fresh, dried moss in the baby frame. Then she wrapped the strong, kicking baby in a blanket and lashed him fast with two broad beaded belts, one red, the other blue. The baby-frame was the finest in the village. Its foot-board was carved as well as the hoop or bow which was placed arching over the child’s head to protect it in case of a fall. Molly folded and placed at one side the cloth which was sometimes drawn over the bow for shade.

Then she, too, sat down upon the ground. As the wind began to blow, the play trinkets hanging from the arched hoop set up a merry tinkle. The pretty shells knocked gently against the tiny wooden hoops filled with knitted webs of nettle-stalk twine.

“What are the spider webs for?” asked Molly, pointing with her finger.

“To keep away evil,” answered Shining Star. “As a spider web catches each thing that touches it, so the knitted webs will catch flying evil before it can harm little Blue Jay. Grandmother Red Bird made them. She is well versed in wisdom.”

“But how can he play,” asked Molly, “with his hands tied tight? How can he learn “to use his hands if they are always tied tight in blankets?”

Shining Star raised her head and smiled. “It is the Indian way,” she said simply. “The Senecas have always done so.”

Molly was fast learning how different Indian ways were from white people’s. It seemed strange there could be such different ways to do the same things. At home her baby brother was left free to wave his arms, crawl or kick at will.

“The Indian child grows strong and straight,” Shining Star went on, “with his back to the hickory board. The Indian child, with his hands tied close, learns patience. Before he can walk alone he has learned a hard lesson.”

“All he can do is open his mouth and cry,” said Molly, looking down at him thoughtfully, “but he doesn’t do that very often. Tied up in a tree and left swinging, no wonder he imitates the call of the blue jay! “

“His first words were spoken to the birds in the tree,” said Shining Star softly. “That is good. His life will be spent in the forest. The birds and the beasts will be his friends. He will learn many lessons from his brothers of the forest. He will follow the trail with the scent of the bear or the wolf. He will build more wisely than the beaver, climb with more daring than the raccoon. He will work more faithfully than the dog; crouch more closely and spring more surely than the panther. He will learn cunning from the fox, the power of swift feet from the deer.

“He will learn to be as brave, as uncomplaining as his brothers of the forest. The hurt dog, the wounded wolf or bear, the dying deer never cries out in pain. The beasts bear their pain in silence, giving no outward sign. They go forward bravely to meet danger. They shrink not from pain or suffering, sickness or death. When little Blue Jay learns to be as brave and uncomplaining as his brothers, he will be a brave man indeed.”

Shining Star looked at Corn Tassel thoughtfully. Was she thinking, not of a wounded animal, not of Blue Jay, but of a white girl captive who was in need of courage? Shining Star had chosen her words with care. She seemed to know that a conflict was going on in the white captive’s mind.

As Molly listened, she looked away from the Indian woman. She wanted to close her ears to the words and yet she wanted to hear them. They gave her a sense of peace she had not felt before and at the same time she feared them. One part of her mind wanted to listen. The other part steeled itself hard against the woman and all that she stood for.

A voice in Molly’s heart kept crying out to make her hear: “You must not love Shining Star. There is a purpose behind her kindness. If you listen to her words and love her, she will turn you into an Indian.” An answering voice cried out: “How can a girl torn away from her people live without affection? How can I live without someone to love?”

“But I don’t

want

to turn into an Indian!” The words leaped out of her mouth before she knew it, tell-tale words that gave Shining Star a glimpse deep down into her aching heart. The tears came and Molly could not hold them back.

“An Indian child never cries,” said Shining Star, calmly. “Loud sounds of grief might attract a wolf or panther or some enemy of the Senecas. Like his brother in the forest, the child must learn to bear his pain and give no sign. He must have courage to suffer bravely. Can you be as brave as a wounded deer?”

Shining Star knew the white captive carried sadness in her heart. Shining Star was trying to help her. Molly dried her tears quickly. Surely a white girl could show courage like an Indian…

“Come, we must go to the corn-field,” said Shining Star, laying aside her work. She always knew when they had talked enough.

“After all—I shall not finish the basket today. Better to weave more slowly…but more surely… Then there will be no need to unravel what has been woven before.”

Molly looked into her face, surprised. Was there some hidden meaning behind the words?

She picked up the heavy baby frame and with the woman’s help, loaded it onto her back. She was accustomed to the burden now and took it up without thinking. As day by day it grew heavier, she knew she was growing stronger, too, to bear it. As she was used to the burden, so was she growing used to all the Indian ways.

Already in four moons she had learned so much. She had learned that by prompt obedience she avoided punishments, even Squirrel Woman’s ever-ready kicks. She had learned that Indian words spoken instead of English brought forth pleased smiles. She had learned that when she worked hard, she was given good food to eat. She had learned that an Indian baby can be as lovable as a white one. Now she had learned one thing more—that the cold look on the face of an Indian was not indifference. She knew now that he suffered as much as others, but he bore his pain without a sign, because he had great courage.

When they reached the corn-field, they met a group of women and children carrying water vessels, hurrying toward the creek. Behind them walked Bear Woman, slow and majestic. Her face was wrinkled and stern. With many winters upon her head, her back was bent with age.

“The corn stands still,” she said with sorrow in her voice. “It does not grow for want of water. We must quench its thirst.” After a moment she added, “There has been no rain for twenty suns.”

“This field was planted later than the others,” said Shining Star, “after my sister and I returned from Fort Duquesne. The right time to plant corn is when the first oak leaves are as big as a red squirrels foot. Well do I remember, the oak-leaves were half-grown when these seeds were sown. Grandfather Hé-no is not pleased to have us plant corn so late.”

“Grandfather Hé-no has forgotten us,” said Bear Woman, sadly. “Now we must suffer his punishment.” She walked away, following after the women and children.

“Grandfather Hé-no?” asked Molly. “Is he a Chief whose name I have not heard?”

“Grandfather Hé-no is the Thunder God,” explained Shining Star. “He brings rain to make the corn, beans and squashes grow. Today Shining Star will make a song, asking Hé-no for rain.”

Shining Star took Blue Jay from Molly’s back and hung him up on a limb. Then she and Molly joined the water-carriers. They brought many vessels of water which they poured at the feet of the corn-stalks, soaking the ground thoroughly.

Then the women and children stood by and listened while Shining Star talked to the Thunder God:

“Oh Hé-no, our Grandfather,

Come to us and speak kindly,

Come to us and wash the earth again.

When the soil is too dry

The corn cannot grow.

The beans and the squashes are dry and withered

Because they are thirsty.

Hé-no, our Grandfather

Does harm to no man;

He protects his grandchildren

From witches and reptiles;

He washes the earth,

Gives new life to the growing corn.

For all thy gifts

We thank thee, oh Hé-no!

Come to thy grandchildren—

Bring rain! Bring rain!”

That evening, after Shining Star and Molly had eaten, they heard the noise of a soft rumble, like thunder far away. They hurried out to look, followed by the rest of the family. The sky that had all day been cloudless, began to darken.

“Hé-no has heard us,” said Shining Star, with a happy smile. “He is coming to visit us.”

With amazing swiftness the storm rolled up, a dense black cloud sweeping furiously eastward. Over the Indian village, thunder soon broke with deafening peals and lightning flashed in sheets of flame.

Molly ran back to the lodge door, frightened. The sky made her think of a hymn the white people had sung in Marsh Creek Hollow:

“Day of wrath! O day of mourning!

See fulfilled the prophets’ warning,

Heaven and earth in ashes burning!”

She ran to get away from the fury of the storm, from the anger of this unknown god of the Indian people. But Shining Star came after her, took her firmly by the hand and led her forth again.

Looking about she saw the Indians, men, women and children, standing in front of their lodges in perfect calm. They had no thought of danger. They gazed at the changing sky in delighted wonder, as the crashes of thunder shook the air and flashes of lightning broke across. When the rain began to pour down in heavy torrents, they held out their hands to welcome it. “It is good! It is good!” they cried. “The corn that was dying of thirst drinks again!”