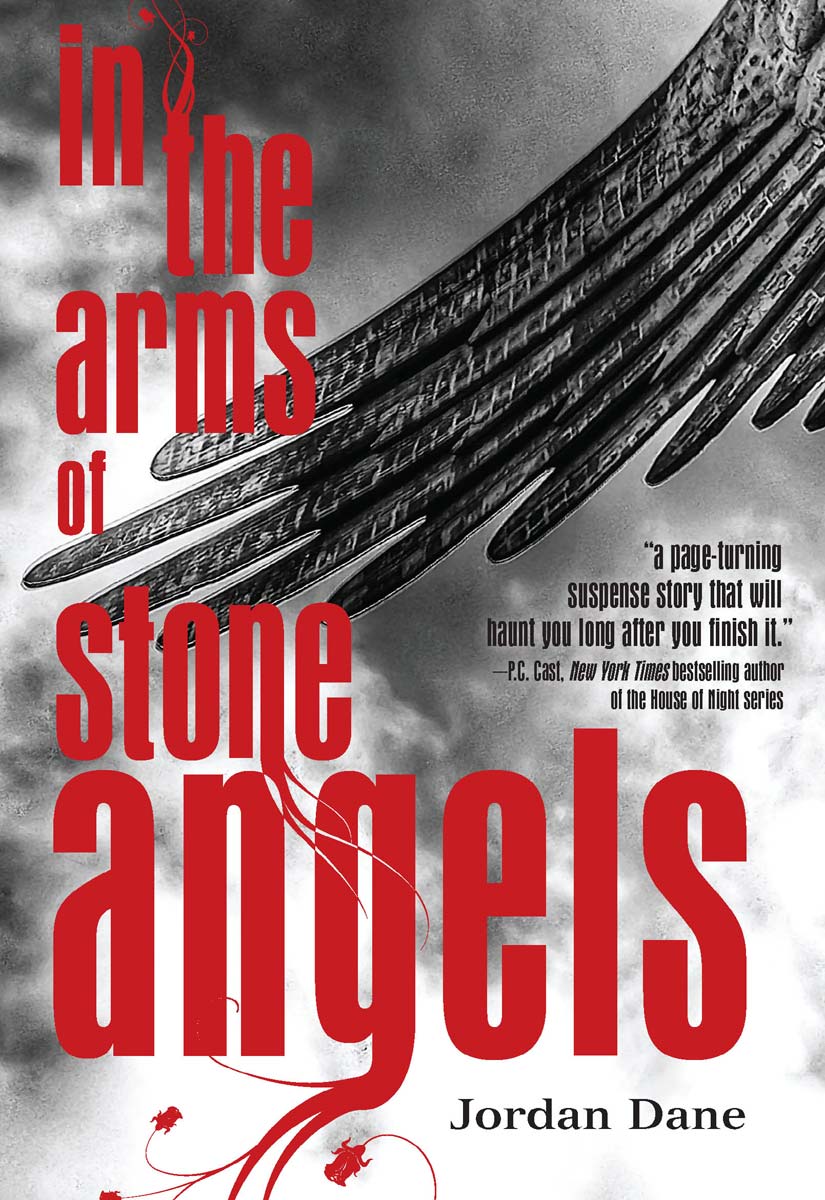

In the Arms of Stone Angels

Read In the Arms of Stone Angels Online

Authors: Jordan Dane

At the mental hospital, I saw a boy slumped in a chair.

He wore hospital scrubs and a white robe with slippers.

And when I got close enough, I took off my sunglasses

and knelt in front of himâcrying.

It was White Bird.

His keen dark eyes were glazed over and empty.

Dead.

With his arms limp, he stared into a world only he could see.

And it broke my heart to see him so lost.

“Oh, my God. What have they done to you?” I whispered,

not recognizing my own voice. “What have I done?”

USA TODAY

bestselling author JORDAN DANE

“

In the Arms of Stone Angels

is eerie,

dark and rich with unforgettable characters.

A page-turning suspense story that will haunt you

long after you finish it. Jordan Dane is a fresh new voice

in young adult paranormal fiction.”

âP.C. Cast,

New York Times

bestselling author of the

House of Night series

“Deliciously dark! Gritty and suspenseful,

In the Arms of Stone Angels

is a new take

on the paranormal. One of the most compelling

and honest voices in young adult fiction!”

âSophie Jordan,

New York Times

bestselling author of

Firelight

Jordan Dane

To my niece, Danaâa kindred spirit

(and lab rat when you thought I wasn't looking).

“in the stillness of headstones, darkness is my blanket. and forever is an endless song. in the arms of stone angels, i'm not afraid. because finally and completely, i belong.”

âBrenna Nash

I sleep with the dead.

I don't remember the first time I did it and I try not to think about why. It's just something I do. My fascination with the dead has become part of me, like the way my middle toes jut out. They make my feet look like they're shooting the finger 24/7. My “screw you” toes are my best feature, but that doesn't mean I brag about them. Those babies are kept under wrapsâjust for my entertainmentâthe same way I keep my habit of sleeping in cemeteries a secret from anyone. Not even my mother knows I sneak out at night to curl up with the headstonesâ¦and the stillness. Some things are best left unsaid.

In the arms of stone angels, I'm not afraid.

I wish I had remembered the part about not telling secrets when I came across my friend White Bird under the bridge at Cry Baby Creek. A woman's spirit cries for her dead baby and haunts that old rusted steel-and-wood plank footbridge. I'd seen her plenty of times, I swear to God. She never talked

to me. The dead never do. She only cried and clutched the limp body of her baby to her chest.

Back then I didn't fully understand how fragile the barrier was between my world and another existence where the dead grieved over their babies forever. And I had no idea that a change was coming. Someone would alter how I saw the thin veil between my reality and the vast world beyond it.

And that someone was my friend, White Bird.

When I saw him crying in the shadows of that dry creek bed, just like the ghost of that woman, the sight of him sent chills over my skin. I should have paid attention to what my body was telling me back thenâto stay away and leave him aloneâbut I didn't.

He was rocking in the shadows and muttering words I didn't understand. When I got closer, I saw he wasn't alone, but I couldn't see the girl's face. And tears were running down his cheeks. They glistened in the gray of morning, at the razor's edge of dawn. I wish I had stayed where I was that dayâhiding in the darkâbut my curiosity grabbed me and wouldn't let go.

Like an omen, the buzz of flies should have warned me. And thinking back, I wish that I had paid more attention to the sound. Even now, a single housefly can trigger that dark memory. And on nights when the dead can't comfort me to sleep, I still hear the unending noise of those flies and I think of him. Our paths had crossed that day for a reason, as if it was always meant to be, and both of us were powerless to stop it.

I remember that morning like it was yesterday and I can't get him out of my head.

White Bird was the first boy I ever loved. He was a half-breed, part Euchee Indian and part whatever. He was an

outcast like me, only I couldn't claim anything cool like being Indian. Because he was half-breed and without parents, the Euchee didn't officially claim him, but that didn't matter to White Bird. In his heart he belonged to the

Dala,

the bear clan of the tribe, because the bear represented the power of Mother Earth. And the strong animal was a totem sign of the healer. The way I saw it, he had picked his clan well.

In school, the teachers called him by his white name, Isaac Henry. But when it was just the two of us, he preferred I call him by his Indian name and that made me feel real special. He was different from the other boys. I was convinced he had an ancient soul. He was quiet and didn't speak much, even to me. But when he did open his mouth, the other kids listened and so did I.

Some people were scared of him because he was taller and bigger than most of the boys and he kept to himself. Sometimes he would get into fights. But after he got his tribal band tattoos, the fights stopped and everyone left him alone, including his teachers. His tattoos made him look like a man. And that was fine by me.

He wore his dark hair long to his shoulders and his eye color had flecks of gold and green that reminded me of a field of wheat blowing easy in the Oklahoma wind. And his skin made me think of a golden swirl of sweet caramel. That's how I thought of him before the nightmare happened. He dominated my mind like a tune I couldn't get out of my head, something memorable and special.

White Bird was my first crush.

And in a perfect world, my first crush should have been unforgettable and magic. But when mine turned out to be the worst nightmare of my pathetic excuse for a life, I knew I'd never deserve to be happy and that magic was overrated.

And as for White Bird being unforgettable, the day I saw him under that bridge covered in blood and ranting like a crazed meth head over a girl's corpse with a knife in his hand, I knew that image would be burned into my brain forever.

It was highly unlikely that I'd forget him and I made sure he'd never forget me. I was the one who turned him in to the sheriff.

Charlotte, North Carolina

Two nights before Mom kidnapped me and screwed up my summer, she told me I was going with her. I didn't want to go back to Oklahoma, but she said I was too young to stay home alone. The real truth was that she didn't trust me. I'd given her plenty of reasons to feel that way. And I had the razor scars to prove it. After she told me, I screamed into her face until I shook all over.

“You never listen. When are you gonna stop blaming me for what happened?” I wanted to throw something.

Anything!

Instead I turned my back on her and headed for my room.

“You come back here, Brenna. We're not done.” My mom yelled after me, but I knew she wouldn't follow.

Not this time.

My heart was pounding and my face felt swollen and hot. I had been out of control and couldn't stop my rage. And when I got in my mother's face, I had seen myself yelling

like I was outside my body. From behind my eyesâin the heat of the momentâI usually don't remember much. But this time I was outside looking down. And I saw my mom's disappointment.

I knew she was afraid of meâand for me. And I still couldn't stop.

I'm a freak.

I'm toxic. I don't know how to change and I'm not sure I want to. When I got to my room, I slammed my door so hard that a framed photo of my dead grandmother fell off a wall in the hallway. The glass shattered into a million pieces.

I didn't clean it up.

I wouldn't.

In my bathroom, I puked until I had nothing left but dry heaves. Whenever I felt like everything was out of controlâthat my life wasn't my ownâthat's when I usually hurled. I knew getting sick wasn't normal, but I didn't care. I refused to let Mom in on my little self-inflicted wound. I didn't want the attention.

When I went to bed that night, I wanted to be alone, but I felt my mom in the house. Hiding in the dark of my bedroom wasn't enough. And when the tears came, I couldn't stand being inside anymore. I slipped out my window in my boxers and tank top, like I usually do, and ran into the open field behind my house toward the old cemetery.

I didn't make it to the stone angels.

I ran, screaming, until my throat hurt. I knew no one would come and no one could hear me, but I wasn't sure anyone would care if I kept running. When I finally dropped to my knees, I collapsed onto my back and stared up into the stars. My chest was heaving and sweat poured off my body, making

the cuts on my bare legs sting. Brambles and weeds had torn up my skin, but the pain wasn't enough.

It was never enough.

My mom had given me no choice. In two days, we'd drive back to Shawano, a town in Oklahoma that I couldn't leave fast enough when I was fourteen.

Just thinking about going backâeven after two yearsâmade me sick. I couldn't catch my breath, no matter how hard I tried. I was dizzy and my chest hurt real bad. And when I thought I would die, I was surprised at how hard I fought to breathe. I had to think about something else, to stop from getting sick again.

That's when my thoughts turned to White Bird and I pictured his face the way I remembered him from before. Seeing him in my mind calmed me even though being involved with him back then had gotten me into trouble. People in Shawano already saw both of us as losers. And my turning him in to Sheriff Logan didn't change that.

In fact, it made things worse. The sheriff connected the dots and interrogated me as an accomplice. He just didn't understand how wrong he was.

Reporting the murder had torn me apart. I couldn't believe White Bird, a boy I trusted with everything that I was, could do such a thing. Seeing him that day made me question everything I believed about him. And I'd never seen a dead body before. The sight had terrified me. I had to tell what I saw. I couldn't just walk away and pretend it didn't happen. But in the seconds it took me to call 911âtrying to do the right thingâmy life would change forever. And there was no way for me to know how bad it would get.

After the sheriff cleared me, I was released and never

charged, but that didn't mean I was innocent in the eyes of everyone in town. And it didn't mean my mom wouldn't feel the pain of guilt by association. Her real estate business dried up and I knew she blamed me.

I never liked that boy. Now look what you've done.

I heard her words over and over in my head. And I can still see the look in my grandmother's eyes the day we left Oklahoma and moved to North Carolina. I talked to my grandmother on the phone plenty, but I heard it in her voice. Even Grams had lost faith and she died not believing in me. Not even the stone angels gave me comfort the day she left this world behind. And when I didn't go to her funeralâbecause I believed Grams wouldn't want me thereâI think my mother was relieved.

Now my mom had to settle my grandmother's estate and get her old house ready to sell. At least that's what she gave me as the reason we had to drive back. I'm not sure I believed her. I was more convinced that she wanted to torture me for what I had done to her life, too.

Lying on my back in the field, I stared into the universe and its gazillion winks of light and made a pact that I would never lie to the stars or make promises I wouldn't keep. Whatever I promised under the night sky should be honest and true because stars were ancient beings that watched over the planet. They wouldn't judge me. Every star was a soul who had died and broken free after they'd learned the lesson they had been born to master.

Me? I was in remedial class. I had more than a lifetime to go. Plus I had a feeling some Supreme Being had me in detention, too. So, speaking the truth, I had to admit that a part of me wanted to go back and see what had happened to White Bird.

But a darker, scarier part wished I'd been the one he had killed under that bridge. And that was the honest to God truth.

Three Days Later on I-40âMorning

“You hungry? There's a truck stop ahead. We can get some breakfast.”

My mother's voice jarred me. On day two of our trip, I'd been staring out the car window watching nothing but fence posts, scrub brush and billboards fade into early-morning oblivion. Not even my fascination with friggin' roadkill had brought me out of my waking coma. And I hadn't spoken much to Mom since she'd told me about this road trip to hell.

“Whatever.” I mumbled so she'd have to ask me what I'd said.

She never did.

Mom filled up the tank of our Subaru and pulled in front of a small truck stop café. Inside, the place smelled like cigarette smoke and old grease. And as I expected, everyone stared at me. I was used to it. I wasn't your average Abercrombie girl. I didn't wear advertising brand names on my body.

It was a life choice.

A religion.

I got my clothes from Dumpster diving and Goodwill, anything I could stitch together that would make my own statement. Today I wore a torn jean jacket over a sundress with leggings that I'd cut holes into. And I had a plaid scarf draped around my neck with a cap pulled down on my head. My “screw you” toes were socked away in unlaced army boots. And I hid behind a huge pair of dark aviator sunglasses, a signature accessory and only one in a weird collection I carried

with me. I liked the anonymity of me seeing out when no one saw in.

The overall impact was that I looked like an aspiring bag lady. A girl's got to have goals.

In short, I didn't give a shit about fitting in with the masses and it showed. I'd given up the idea of fitting in long ago. The herd mentality wasn't for me. And since I made things up as I went, people staring came with the territory. Mom picked a spot by a window and I shuffled my boots behind her and slid into the booth.

I grabbed a menu on the table and pretended to look at it while I played with my split ends.

“Do you have to do that here?”

“Do what?”

Neither one of us expected an answer.

I seriously hated my hair. It was long, thin and stringy, like me. A washed-out blond color that bordered on red. In the frickin' sun I looked like my damned head was on fire.

“You ready to order?” The waitress didn't even pretend to smile.

I asked for nachos with chili and my mom ordered a salad and coffee. Neither of us had a firm grasp of the term

breakfast.

It was one of the few things we had in common. While we waited for our food, Mom opened a valve to her stream of consciousness. Guess the quiet drive made her feel entitled to cut loose. And her talkative mood didn't change after we got our order. She jumped from one topic to another with her one-sided conversation, spewing words into the void like people do on Twitter.

Me? I scribbled in a spiral notebook while she talked. I always had a notepad stuffed in my knapsack and a collection of old notes piled in my closet back in North Carolina. Whenever

I got an idea for clothes I wanted to make or a line of poetry or a lyric that got stuck in my head and wouldn't come out until I wrote it down, that's what usually went on paper. All I was working on now was a layered hoodie skirt thingee that was beginning to look an awful lot like a Snuggie. It looked like crap, but I probably wasn't drawing it right. Maybe Dana would wear it.

My only real friend in NC was Dana Biggers, who'd been texting me. She was okay, tolerable even. I hadn't written her back. She was asking too many questions about my trip and I didn't want to explain it, thinking I might tell her too much. I'd worked hard at keeping my old life in Oklahoma a mystery. I had wanted to reinvent myself and start over. Texting her back might ruin that, so I didn't. She'd get over it.

Dana was Wiccan and she practiced magic 24/7. Because of her, I got a B-in biology this term. It was the only class we shared, so I figured she had the goods if she could deliver one shining moment in a lifetime of my underachievement. We both needed extra credit, so after we dissected our frog, we took the teacher's challenge and removed the brain whole. I used a blade, but Dana got her Wiccan mojo on and chanted her part. The frog's brain squished out in one piece. The teacher shook his head, but gave us the credit anyway.

Dana swears that I was a witch in another life. Who am I to argue with that? I know she's full of shit, but she lets me make clothes for her and she doesn't laugh when I read her my old poems. Like I said, she was okay. Kind of cool, actually.

Since I'd left Oklahoma, I hadn't written anything. I missed it, but I had a hole in me that I couldn't fill with poetry or music or making clothes. And unlike Mom and what she was doing now, words didn't come easy for me, not after what had happened two years ago.

Although I couldn't be certain, I figured Mom's talking was her way of making an effort to bond. And I had to give her props for timing. I was captive in a moving vehicle for two days. And if she didn't give me a brain bleed from the ritual, she had a pretty good shot at nabbing my attention once in a while. Picking at my nachos, I'd only heard every six and a half words as I scribbled until she finally got my full attention.

“You knowâ¦I heard that boy is still locked away in a mental hospital outside Shawano.” Mom kept her face down and shoveled her fork like she was being timed. And her talking about White Bird, and referring to him as “that boy,” had forced me to listen, especially when she said, “They say he never came out of it.”

I stopped scribbling. Cold.

Parents always had “they” to back them up. And “they” were always right. Kids had squat. It was hard to compete with “they.” I wanted to roll my eyes because I knew that would piss her off, but I got to thinking about White Bird and what “still” meant.

“Still? You mean he's been there since⦔ I couldn't finish. All this time, after I had moved away and taken my miserable butt to North Carolina, White Bird had been locked away. Knowing that twisted my gut into a knot. I felt worse than I ever did before.

And that was saying something.

“Yes. That's why you were never asked to testify. His case never went to trial because of hisâ¦condition,” Mom explained.

I had been so wrapped in my own misery that I had missed the obvious. Mom was right. And I'd never asked about going to court, to say what had happened. I should have known.

I should have thought about what that meant for him, but I never did.

“Why didn't you⦔

Tell me! Tell me! Tell me!

I wanted to scream, but instead I turned to look out at the parking lot and said, “Never mind.”

All I wanted to do was lash out at Mom and blame her for my frustration. I knew it wasn't fair, but I also knew she'd let me get away with it.

White Bird had never gotten his day in court. Where had he gone? Was he still inside his head, unable to find his way out of a dark maze? Or had he clicked off like a light switch, never to return? What had happened that night to cause such trauma?

“He never says anything. That boy just sits and stares at nothing.” Mom looked up from her salad, making sure I got the point. “Maybe next time you'll listen to me when I tell you some kid isn't right in the head.”

Mom always knew how to throw cold water on me. Plus her timing sucked. And although she didn't come right out and say it, her eyes were filled with the message “I told you so.” I resented her smugness, her certainty that being an adult always made her right, but I didn't have much going for my side of the argument. With White Bird branded as a crazed lunatic, that was one point for Mom.

Zip for me.

“I'm not afraid of him,” I said as I chewed my thumbnail and stared out the window into the bright sunlight from behind my shades. If it were dark and the stars were out, I'd never let me get away with lying.

“Well, you should be, young lady.”

White Bird had given me plenty of reason to be afraid. And what had happened two years ago would always be with me.

I still had trouble sleeping through the night. In many of my dreams, I was the one he stabbed. I watched him do it, over and over. And each time I felt the pain like it was real. I tried to get away, but I couldn't move. Everything slowed to a crawl like I was sinking into quicksand and heavy mud oozed down my throat so I couldn't scream.