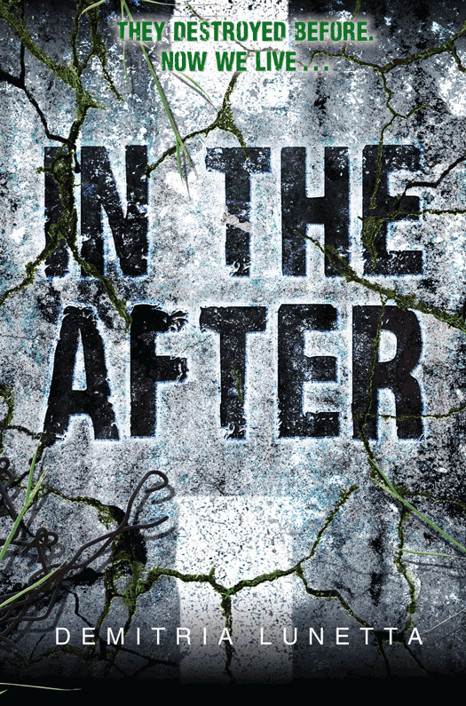

In the After

Authors: Demitria Lunetta

Contents

ContentsAcknowledgments

There are so many people involved in making this book come to be. I want to thank

my amazing editor, Karen Chaplin, who made me dig deep and helped me build such a

wondrously frightening world. I would also like to thank everyone at HarperTeen—my

supportive editorial director, Barbara Lalicki, and always-helpful editorial assistant,

Alyssa Miele; my fantastic designer, Cara Petrus, who made the book come alive in

such an amazing way; the detail-oriented production department, including production

editor Jon Howard, who corrects my sometimes-incorrect use of grammar; and the awesome

marketing and publicity departments, including Kim VandeWater, Lindsay Blechman, and

Olivia deLeon. You have all done such an incredible job. This book would not be what

it is today without all of you. I couldn’t ask for a better team.

I’d also like to thank Maria Gomez, who responded so positively to my book. I’ll always

remember our first phone conversation in which she was as excited about

In the After

as I was.

Lastly, I’d like to thank Katherine Boyle of Veritas Literary. You’re, quite simply,

Awesome with a capital A. You’re the best agent anyone could ask for.

CHAPTER ONE

I only go out at night.

I walk along the empty street and pause, my muscles tense and ready. The breeze rustles

the overgrown grass and I tilt my head slightly. I’m listening for Them.

All the warnings I remember from horror movies are wrong. Monsters do not rule the

night, waiting patiently to spring from the shadows. They hunt during the day, when

the light is good and their vision is at its best. At night, if you don’t make a noise,

they can shuffle past you within an inch of your nose and never know you are there.

It’s so very quiet, but that doesn’t mean that They are not near. I walk again, slowly

at first, but then I pick up my pace. My bare feet pad noiselessly on the cracked

sidewalk. Home is only a few blocks away. Not far if I remain silent, but it may as

well be miles if They spot me.

I’ve learned to live in a soundless world. I haven’t spoken in three years. Not to

comment on the weather, not to shout a warning, not even to whisper my own name: Amy.

I know it’s been three years because I’ve counted the seasons since it happened. In

the summer before the After when I’d just turned fourteen.

A branch snaps in the distance and I stop immediately, my body tense. I shift my bag

slowly, carefully adjusting the weight so the cans inside don’t clank together. Every

little noise screams at me that something is wrong, but it could be nothing.

Clouds shift and moonlight suddenly brightens the street. I glance around, searching,

studying an abandoned, rusted car for any signs of the creatures. When I don’t spot

Them, I almost continue on, but at the last second I decide to play it safe. Stepping

into an abandoned yard, I disappear into the shrubbery. I’ll wait until a cloud passes

in front of the moon and darkness reclaims the night.

I can’t take any chances, not with Baby waiting for me. My bag holds the food we need

to survive. We only have each other. I found Baby shortly after the world failed,

when I still believed things would return to normal. I no longer hold that hope. Nothing

this broken can ever be fixed.

This is how I think of time: the past is Before, and the present is the After. Before

was reality; the After, a nightmare.

Before I was happy. I had friends and sleepovers. I wanted to learn how to drive,

to get a jump start on my learner’s permit. The worst thing in my life was math homework

and not being allowed to date. I thought my parents were so clueless; my dad with

all his “green” concerns (I told my friends he was an eco-douche), and my mom, who

was never home except for Sunday-night family dinner. I was kinder to my mom, though,

and only called her a workaholic. Her job was with the government, her work very hush-hush.

I always thought of myself as smart, and I was definitely a smart-ass to my parents.

I loved seeing them squirm, letting them know that I didn’t buy into their “because

I said so” crap. I was good in school. I could always guess the endings of movies

and books. Now there is no school, there are no more movies, no new books, no more

friends.

The creatures arrived on a Saturday. I know it was a Saturday because if it were a

weekday I would have been at school and I would be dead. Sundays I went with my father

to visit his parents at Sunny Pine, and if They had come on a Sunday I would also

be dead.

I remember that the electricity flickered and I was annoyed because I was watching

TV. I had wondered if my father was on the roof screwing around with the solar panels.

They didn’t require much maintenance, but he liked to hose them off twice a year,

which always messed with all our electronics. I checked the garage. His electric car

was gone. He was at the farmers’ market, probably overpaying for organic carrots.

I microwaved some pizza bagels (the ones my mom hid from my dad at the back of the

freezer) and sat back in front of the TV, flipping through the channels mindlessly.

I’d wished my parents would listen to me and upgrade to the premium cable package.

I thought life was so unfair. My mother had bought my father a brand-new electric

car for more money than I would probably need for college, but she wouldn’t spend

fifty bucks extra a month to get some decent television.

I checked my cell phone but there were no calls from Sabrina or Tim. I was supposed

to go to a movie with them later. Tim had been madly in love with Sabrina forever

but her parents would only let her go out with him if I tagged along. I joked with

Sabrina about being the old spinster in a nineteenth-century novel. “No secret love

child for you two,” I’d tell her with a wink. “Not while Matron Amy is on duty.”

I didn’t really mind being their chaperone; they never made me feel awkward or like

a third wheel. Sabrina hadn’t even decided if she was all that into Tim. I’d been

friends with her since fifth grade, when I was the weirdo who skipped a grade and

she was the nice girl who didn’t treat me like I had the plague. Pretty soon we were

friends and stayed besties through middle school and into high school.

I tossed my phone on the coffee table and kicked up my feet, giving my full attention

to the TV screen for the first time. But I noticed that even when I changed the channel,

the picture stayed the same. I paused, curious. The president was making a speech.

Boring. I ate my snack, only half listening.

“It has come to our attention,” the president droned, “that we are not isolated in

this attack.”

I sat up, my bite half chewed. Attack? I was too young to remember the string of terrorist

attacks at the beginning of the century, but my mother worked for the government and

was constantly talking about our “lack of counterterrorist mechanisms.”

I turned up the volume. The president looked exhausted, bags under his eyes, makeup

caked on for the cameras. “The structure landed in Central Park early this morning,”

he said into twenty microphones. “As of now, the fate of anyone residing in New York

City and the surrounding suburbs is unknown. We are working to find the cause of this

interruption in communication as soon as—” He was cut short. The breaking news logo

flashed across the screen.

I took a swig of soda. It was strange that the network had interrupted the president.

I didn’t understand what they were talking about, didn’t know what it all meant yet.

I glanced at the screen and what I saw nearly made me choke on my soda. They had footage

of the “structure” in the park. Something emerged, turned toward the camera, stared.

Still coughing, I pressed

PAUSE

on the DVR remote and stood.

That was the first time I saw an alien.

After They came, I did not leave my house for three weeks. The broadcasts stopped

after the first few days, but they were not helpful anyway. They kept repeating the

same things. Aliens had landed, they were not friendly, half of the planet was dead.

They were horrifyingly fast, traveling across the globe at an alarming pace. They

didn’t destroy buildings or attack our resources, like in so many crappy Hollywood

movies. They wanted us. They hungered for us.

That first day, I was slow to understand what was happening.

My hands shook as I desperately tried to call my friends and family. My father didn’t

carry a cell phone. He didn’t believe in them, said they gave people brain cancer.

My mom had one of those fancy touch-screen phones that her job paid for, but she never

answered, and her office line went straight to voice mail. Sabrina’s phone just rang

and rang. So did Tim’s. I tried my cousin in Virginia and my mom’s parents in Miami.

No one answered. I went through the phone book on my cell, furiously calling one number

after another. Eventually I could no longer dial out. I kept getting a recorded message.

“All circuits are busy. Please hang up and try your call again at a later time.” Soon

I couldn’t even get service. I stared at the screen for a minute, then, frustrated,

threw the phone against the wall.

I curled into a ball on the couch and tried not to cry, but I couldn’t hold back the

tears for long. When my father didn’t come back after a few hours, I had to admit

to myself that he was dead. He had camping skills, but I could not imagine him holding

his own against an alien attack. My mother might be okay, her government offices were

high security, surrounded by soldiers. But I had no idea how to reach her, and could

soldiers really protect her from those repulsive creatures? I had to face the reality

that my parents could both be gone.

I stayed on the sofa and cried until I had no tears left and not enough energy to

sob. I eventually crawled to the fridge and grabbed my dad’s Ben and Jerry’s from

the freezer. It was the one junk food he allowed himself. He said life wasn’t worth

living without Cherry Garcia. I gorged myself on ice cream and ended up vomiting purple-pink

onto the floor. I fell asleep there, exhausted and miserable.