In Tasmania (16 page)

Authors: Nicholas Shakespeare

â

THE MOST INTERESTING EVENT IN THE HISTORY OF TASMANIA, AFTER

its discovery, seems to be the extinction of its ancient inhabitants.'

In 1875, Kemp's obituarist James Erskine Calder sat down to write

The Native Tribes of Tasmania

. So far as he knew, one full-blooded Aboriginal remained alive on the island. A year later Truganini was dead. With her passing, it came to be generally accepted what Darwin had written â âVan Diemen's Land enjoys the great advantage of being free of a native population' â and that the Tasmanian Aborigines had shared the fate of the Beothuks of Newfoundland: two distinct races which became extinct in the nineteenth century. But Truganini's death was not the end of the story.

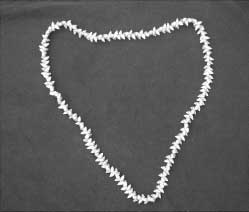

I had been only a few weeks in Tasmania when, on a visit to her house in Hobart, I saw my new-found Kemp cousin produce a faded Edwardian case of the sort used for storing fish knives. She carried it to the table and opened it. Inside on the felt was a halo of green Mariner shells, each the size of a child's tooth.

I had seen shell necklaces before, but nothing like this.

âTo get that colour,' she said, âthey soaked the shells in urine and scratched the outside off.'

âWhere does this come from?'

âIt was Truganini's,' her face solemn. And she told how Truganini used to call at the kitchen of her grandmother's three-storey house in Battery Point, and ask for food and grog, usually hot ale and ginger, and in return Truganini gave the daughters of the house necklaces. âGranny kept the necklace in the china cabinet and we would play dressings-up with it. It was so long that I would wind it two or three times around my neck.'

I lifted the frail circle, and imagined the hands that had polished and strung these tiny shells. James Bonwick had described Truganini as âexquisitely formed, with small and beautifully rounded breasts'. An American captain who entertained her on board his ship towards the end of her life was transfixed by âher beautiful eyes'. Margaret thought that Truganini had started coming to the house in Hampden Road after the last male Aborigine died and his head was stolen. She said that Truganini was desperate, upset, miserable.

âIt didn't mean anything to us. At school, we were told Truganini was the Last Tasmanian, but no-one was very interested. I knew it wasn't true.'

âWhat do you mean it wasn't true?'

Margaret said that she had grown up with Aborigines and that now there were many on the island who called themselves Tasmanian Aborigines.

âHow many?' She smiled. âAbout 15,000.'

This was four or five times the accepted number that had been on the island when Kemp arrived.

I was excited and pestered her with questions. How had they kept their culture? What did they look like? Where would I find them?

Margaret warned that it would not be straightforward. The majority looked âlike you and me' and had white faces and blue eyes. She and her friends never made conversation about Aboriginal people in a public place. âBecause you never know who is an Aborigine.'

THE VIEW OF THE

â

ORTHODOX

'

SCHOOL, SOMETIMES CALLED BY ITS

detractors the âblack armband' school, is that the English colonists â in the space of 73 years â wiped out the Tasmanian Aborigines, if not as a deliberate act of genocide then as an unfortunate but inevitable concomitant of frontier warfare and disease. It was a view expressed as early as 1853 by the traveller F.J. Cockburn: âHere, as in most other places, it has been the old story â aggression on our part, retaliation on theirs, and then persecution on our part for safety's sake.'

But since 2000 there had sprung up a newer, more contentious and revisionist version of Tasmanian history: we did not kill very many, they were all dying out anyway, we do not have too much to worry about. Therefore, we do not owe the Aborigines any apology, compensation or land.

I went to a debate in Hobart between these rival factions, hoping to learn more. The invasion of Iraq was eight days old and the news dispiriting. British soldiers had not been greeted, as expected, with âtea and rose petals'. A young man from

Jane's Defence Weekly

talked on the radio about the tactical misinformation put about by a Ministry of Defence spokesman. The young man had trained as a journalist. âWhere is the second source for the story of a woman in Basra hanged after she waved at British forces?' He complained that we were only getting one side of the story: our side.

The lecture in the Dechaineaux Theatre was billed as âTelling Histories' and took place on the wharf where both Kemp's warehouse and Hobart's original execution site had stood. I spotted the author Keith Windschuttle in a tight green suit and open blue shirt. He glanced round, neon blazing from his sunburned pate. It was a full audience and people were standing against the walls. Like me, they had come to hear Windschuttle debate the fate of the Tasmanian Aborigines, about which he had recently self-published a book that was dividing opinion on the mainland. The historian Geoffrey Blainey had called it âone of the most important and devastating written on Australian history in recent decades'. In the judgment of James Boyce, âthe book is the most ignorant and offensive publication on Van Diemen's Land in at least a century, arguably ever.'

The Chairman introduced the panel. It included Windschuttle, a Sydney academic, former Trotskyist, and author of

The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume I, Van Diemen's Land 1803â1847

; Henry Reynolds, one of Tasmania's foremost historians; and Greg Lehman, a Tasmanian Aboriginal who had successfully lobbied to have Risdon Cove, site of a notorious early âmassacre' by British soldiers, handed back to the Aboriginal community.

The chairman allowed them four minutes each on the subject: âHow do you collect information and what do you decide to leave out?' All exceeded their brief by a wide margin.

Windschuttle was the second speaker. The gist of what he said was this:

Over the past 30 years, university-based historians like Reynolds had presented a widespread picture of killing of Aborigines that in the words of Lyndall Ryan was âa conscious policy of genocide'. Windschuttle had been a true believer of this story for most of his adult life. âI used to tell my students that the record of the British in Australia was worse than the Spanish in South America.' Then, in 2000, he began work on his book, expecting to write a single chapter on Tasmania, and for three years had checked the footnotes of historians like Reynolds and Ryan, along the way discovering âsome of the most hair-raising breaches of historical research imaginable'. After examining all the available evidence he concluded that myth had been piled on myth.

Singling out the man beside him, he gave this example. In 1830, according to Henry Reynolds, Governor Arthur had written of his fear of the âeventual extirpation

of the Colony

[my italics]' â hence his initiation of the Black Line, in which more than 2,000 armed convicts, settlers and soldiers fanned out across the island in a human dragnet to round up all remaining Aborigines. But Reynolds had altered a critical word. What Arthur actually wrote was his fervent hope that by careful measures he could prevent âthe eventual extirpation

of the aboriginal race itself

[my italics].' Reynolds, in other words, had radically changed the meaning of one of the most significant documents in early colonial history.

Windschuttle's thesis was that during the first 30 years of settlement the British had killed 120 of the original inhabitants, mostly in self-defence. This was one-tenth of Reynolds' estimation. In fact, Tasmania was probably the site where the least indigenous blood of all was deliberately shed in the British Empire. âMy quarrel is not with the Aboriginal people at all, my quarrel is with historians who told lies about them.' Those historians who had perpetrated the idea of a genocide had âbetrayed their profession and misled their country'.

In his response, Reynolds remarked that Windschuttle had been dining out on other people's footnotes. âI'm a little concerned about you, Keith,' he said. âI wonder if you had a childhood problem with reading.' The fact was that Windschuttle had misread what Reynolds had written and attributed to him ideas and attitudes that did not exist. There had been no fabrication, other than in Windschuttle's book. In claiming, for instance, that the Aborigines had no concept of land possession, Windschuttle had profoundly misunderstood their culture. What he had produced was a pitiless vilification, âthe most sustained attack on a native Aboriginal community for a long time, and perhaps ever'.

After each of the speakers had had their say, Jim Everett, a Tasmanian Aborigine from Cape Barren Island, stood up at the back. In a steady and dignified voice, he complained that Aboriginality had not been understood in the discussion because it was not part of the discussion. The reason there was no word for land was because âwe define land as something that is part of us â not separate.' He said: âWe continue to be researched and over-researched,' and he looked forward to the day when his community would grow their own historian. At this everyone clapped except Windschuttle.

The last and most devastating question was asked by a black man in a wool cap. His name was Douglas Maynard. His people, he said, came from Wilson's Promontory. He had spent six years working in the archives. âI'm going to ask you historians, where's your integrity?' There had been a conspiracy about genealogy. â

You

know, Mr Reynolds, about it. I'm a black man, I sit here listening to you talking about my people. Mr Jim Everett doesn't know about my people.' Then he delivered an unexpected remark that caused the theatre to erupt in chaos: âI thank Mr Windschuttle for bringing out the fraud that's going on.'

As they filed from the hall, many who had sat through this bunfight asked themselves: What

was

going on?

IT DID NOT TAKE LONG TO REALISE THAT ANY ATTEMPT TO UNDERSTAND

what had happened to the native population in Tasmania was frustrated by the absence from the written record of the Aborigines themselves. Their descendants had to depend on a body of work produced for the most part by âwhite' witnesses, colonisers and historians who did not in every instance agree. The debate had the effect of polarising many of the participants, who assumed fundamentalist positions and were exasperated by the others' intransigence. âSomething about Tasmanians,' says the poet Andrew Sant, âmeans that they find it very difficult to hold two contradictory opinions. There is a tendency for Tasmanians as a small community to box themselves into one camp or the other and for the debate to become heated and, worse, personal.' As with the rivalry between Launceston and Hobart, or between the factions of the Royal Society of Tasmania, there was a lot of rancour, little authentic dialogue and a tendency to take an à la carte attitude to the historical record in order to shore up a settled position. Certainty combined with dismissiveness, and the deepest hostility was generated for anyone caught searching for the middle ground. Beneath the salvoes, the complexity of what took place then, and what was taking place today, risked slipping by unnoticed.

And so I turned back to Kemp. He was not a reliable guide, but he was a devil I knew. He also had a rare, if not unique, knowledge of both Hobart and Launceston.

Â

If my hunch was correct, Kemp's formative contact with Aboriginal culture began on his first voyage to Australia when he was shipmate with Bennelong on the

Reliance

. Six months together in the same cramped space, perhaps learning a smattering of Eora, gave Kemp unrivalled exposure to a people whom

The Times

of London characterised as âexactly on a par' with âthe beasts of the field', and could well explain his initial sympathy. Kemp reminds Henry Reynolds of Colonel C.J. Napier who rejected the idea that Aborigines were âa race which forms a link between men and monkeys', and argued that these âpoor people are as good as ourselves'. In their turn, the Aborigines who watched Kemp come ashore in November 1804 saw him as one of their own. They thought he was a dead Aborigine.

They had known no other people for 9,000 years, ever since Van Diemen's Land was cut off from the mainland. Patsy Cameron is a Tasmanian Aborigine from Flinders Island. âHow would

we

perceive strangers coming off a spaceship that looked like us â but had skin coloured purple?' Her ancestors, she thought, understood Kemp to be Num, an Aborigine who had returned from the home of the departed, a heavenly island that he called England and they called Teeny Dreeny, to which he had travelled on the back of a seal. One day they, too, expected to jump up on an island as white men. âThey would have seen him as a spirit, but they wouldn't have known whether evil or good.'

Kemp had returned from a previous life because he knew the country, and if he behaved in a strange way it was because the trauma of dying had affected him so that he had forgotten how to behave. To begin with, the Aborigines treated him as a child. As he began to learn their language, scattered with whatever words Bennelong had taught him, it was as though he was recalling it. As he began to recognise them, they thought: âOh, he's remembering us, the journey to England has wiped out his memory, and gradually it's coming back.' Meanwhile, they looked at Kemp for some resemblance, some mark or gesture that gave him his kin place. âThey think in kin terms,' Henry Reynolds says. âEveryone is related to everyone. They would try and decide who Kemp had been in an earlier life and then assume that position.' Only much later, when it was too late, would they say: âWe realise you're nothing but a man.'

Â

Kemp watched his men hoist the flag on Lagoon Beach on November 11, 1804. A royal salute was fired from the

Buffalo

plus two volleys from the soldiers. Perhaps attracted by the noise, the first natives appeared the following day, a body of about 80, who approached to within 100 yards. The men were stark naked. The women wore kangaroo skins over their shoulder. Their black hair was woollier than Bennelong's, resembling, to one observer, âthe wig of a fashionable late eighteenth-century French lady of quality'. It was streaked with marrow grease and red ochre, and the reddish-brown skin on their arms was patterned with scars.

Kemp was all set to make friends. He ordered them to be given a tomahawk and mirrors. They looked into the glass and âput their hand behind to feel if there was any Person there'. Tantalised, they stepped closer to the tents â making a grab for tools and clothing. Then disaster. They hauled away a Royal Marine sergeant and were on the verge of throwing him into the sea when he or one of his privates fired a musket, killing one Aborigine and wounding another. The dead man's was the âvery perfect native's head' that Paterson sent in a box to Joseph Banks. Although not on the same scale as the episode at Risdon six months earlier, the incident marked, as Paterson predicted, a transgression. âThis unfortunate circumstance I am fearful will be the cause of much mischief hereafter, and will prevent our excursions inland, except when well armed.'

Almost the next casualty was Kemp's utopian brother-in-law, Alexander Riley, whose belief that he had come to a latitude âconjointly equal to any other spot on earth', and perfect for growing rhubarb, was about to be challenged. Frantic to find a more suitable place for the settlement, Paterson sent Riley off to look for better pastures, but after walking for four hours Riley found his path blocked by 50 Aborigines who made a lunge for his cravat, exclaiming âwalla, walla', and then speared him in the back. He managed to crawl 15 miles to his boat, but he remained in a fever for several weeks. âMr Riley has not been well since,' wrote Paterson. âI rather think the Spear has penetrated close to the spine.'

Months later, Paterson appointed Kemp acting Lieutenant Governor. These were the instructions that he passed on regarding the Aborigines: âYou are to endeavour by every means in your power to open an intercourse with the natives, and to conciliate their goodwill, enjoining all persons under your Government to live in amity and kindness with them; and if any person shall exercise any acts of violence against them, or shall wantonly give them any interruption in the exercise of their several occupations, you are to cause such offender to be brought to punishment according to the degree of their offence.'

How much Kemp abided by his orders is hard to tell. But there is evidence to suggest that he continued to take the Aboriginal side, despite their assault on his brother-in-law. The surgeon who dressed Riley's wound was Jacob Mountgarret, who had arrived from Hobart with an Aboriginal boy, three or four years old, with ânice' table manners. Mountgarret had adopted the boy and named him Robert Hobart May. Robert was able to tell Kemp his story without any âfear or apprehension': how his parents were killed in front of him at Risdon by soldiers with whom Kemp had served in Sydney.

Â

Risdon Cove on the east bank of the Derwent was the site of the first settlement in Hobart. What happened there on an autumn day in May 1804 was, wrote Mark Twain, out of all keeping with the place: âa sort of bringing of heaven and hell together'.

Twenty-six years after the event, a former convict Edward White testified that he was hoeing ground near the creek when there suddenly appeared a circle of 300 Aborigines, including women and children, hemming in a mob of kangaroos. âThey looked at me with all their eyes,' White remembered, suggesting that the sight of him turning the soil was the first indication that they had had of any English settlement on the island. The Aborigines reportedly belonged to the Oyster Bay tribe. White was positive, he said, âthey did not know there was a white man in the country when they came down to Risdon'. The Aborigines did not threaten him and he claimed not to be afraid of them. Even so, White reported their presence to some soldiers and resumed his hoeing. Then, at about 11 a.m., he heard gunfire. The great difficulty is to imagine what happened in the next three hours until, at about 2 p.m., troops under the nervous command of Lieutenant Moore apparently fired grapeshot into the crowd, who had, Moore claimed, turned hostile.

According to White, âthere were a great many of the Natives slaughtered and wounded; I don't know how many'. Nor can anyone else know how many. The truth floats between the written record â which is that three Aborigines died, including Robert Hobart May's parents â and the oral record, which is that up to 100 died. But the incident stuck in the historical memory and, likened frequently to Eve's bite of the apple, came to be understood as the original transgression.

In September 1830, at a time of maximum tension in the colony, Kemp remembered Robert's composed testimony when chairing an urgent meeting in the Hobart Court House. The hall was packed with the colony's most prominent citizens and Kemp was first to address them. What he said, although prolix, was not quite what anyone expected. âMr Kemp commented at some length upon the aggressions committed by the blacks, which he attributed in a great degree to some officers of his own regiment (the late 102nd) who had, as he considered, most improperly fired a four-pounder upon a body of them, which having done much mischief, they had since borne that attack in mind and have retaliated upon the white people whenever opportunity offered â¦'

Henry Reynolds says: âIt's a pretty extraordinary thing to say about your own regiment. A regiment is like a club. Even a cad doesn't badmouth his own regiment.' Kemp went further in his condemnation when speaking to the historian James Bonwick. Although referred to only as âa settler of 1804', he is the probable source of Bonwick's story that Robert Hobart May's parents were shot at Risdon during âa half-drunken spree ⦠from a brutal desire to see the Niggers run'. Kemp repeated his version to a commission of inquiry in 1820 as a way to explain the bitter attitude of the Aborigines: âthe spirit of hostility and revenge that they still cherish for an act of unjustifiable violence formerly committed upon them'.

Â

And yet what is perhaps remarkable about the first 20 years of European occupation is the absence of clashes. Following Riley's spearing, colonists settled into a relatively amicable relationship with Aborigines. Kemp's protégé Jorgen Jorgenson, for instance, thought them âinoffensive and friendly'. The two groups traded with each other, the settlers offering sugar, tea and blankets in exchange for kangaroos, shellfish and women. As late as 1823,

Godwin's Emigrant Guide to Van Diemen's Land

wrote of the Aborigines that âthey are so very few in number and so timorous that they need hardly be mentioned; two Englishmen with muskets might traverse the whole country with perfect safety as they are unacquainted with the use of fire-arms.' In March 1823, George Meredith, a good friend of Kemp, wrote in appreciative terms to his wife about a group of naked Aboriginal women encountered in a small bay on his way to Swansea. âWe were honoured by the visit of six black

ladies

to breakfast next morning who caught us craw fish and Mutton Fish [abalone] in abundance in return for bread we gave them â you would be much amused to see them Swim and Dive. Although I do not think you would easily reconcile yourself to the open display they make of their charms. Poor things, they are innocent and unconscious of any impropriety or indelicacy. They were chiefly young and two or three well proportioned and comparatively well looking. So you see had I fancied a Black wife I had both opportunity and choice.'

7

Plenty of sealers and bushrangers availed themselves of this opportunity â like Michael Howe, whose companion, Black Mary, Kemp had interrogated in 1817. But by the mid-1820s the situation had shifted. Aborigines were no longer prepared to surrender their women and children to Europeans without a fight. They observed with mounting alarm how these Num not only raped and beat their âlubras', but infected them with âloathsome diseases', often with the result that they were unable to breed. Twenty-six years after Kemp's arrival there were not enough Aboriginal women on the island to sustain the dwindling population. Of the 70 or so natives who remained in the north-east by 1830, only six were women. None were children.

The Aborigines resented, too, the way that settlers like Kemp and Meredith seized their best hunting grounds, the grasslands and open bush that supported the densest populations of wallaby and kangaroo. Under Governor Sorell grants to new settlers soared to almost one million acres. By 1831, the European population had further doubled (to 26,640), two million acres of native woods and grassland had been ceded, and the numbers of sheep grazing on the land had increased five-fold. Around Swansea, Meredith was able to fence off large tracts of land, including not only the beach where I now lived, but Moulting Lagoon behind our house, a vital gathering place for the Oyster Bay tribe. Deprived of their women and their food supply, the Aborigines retaliated. By 1825, Meredith was warning his wife: âThe natives, I fear, must now be

dispersed wherever

they make their

appearance

.'

The Oyster Bay people were regarded by the man who subdued them as âthe most savage of all the aboriginal tribes'. Their chief was Tongerlongetter, derived from the Aboriginal words meaning âheel of the foot' and âgreat'. He was a gigantic figure who measured six feet eleven inches and was capable of drinking a quart of tea at a sitting. He used rust from the bolts of shipwrecks to colour his ringlets, and had scars in the small of his back, tattooed with an oyster shell, that resembled dollar coins. Known in captivity as the old Governor or King William, Tongerlongetter was a robust, intelligent leader, a man of âgreat tact and judgement' in the opinion of George Robinson, who was responsible for persuading the chief to lay down his arms.