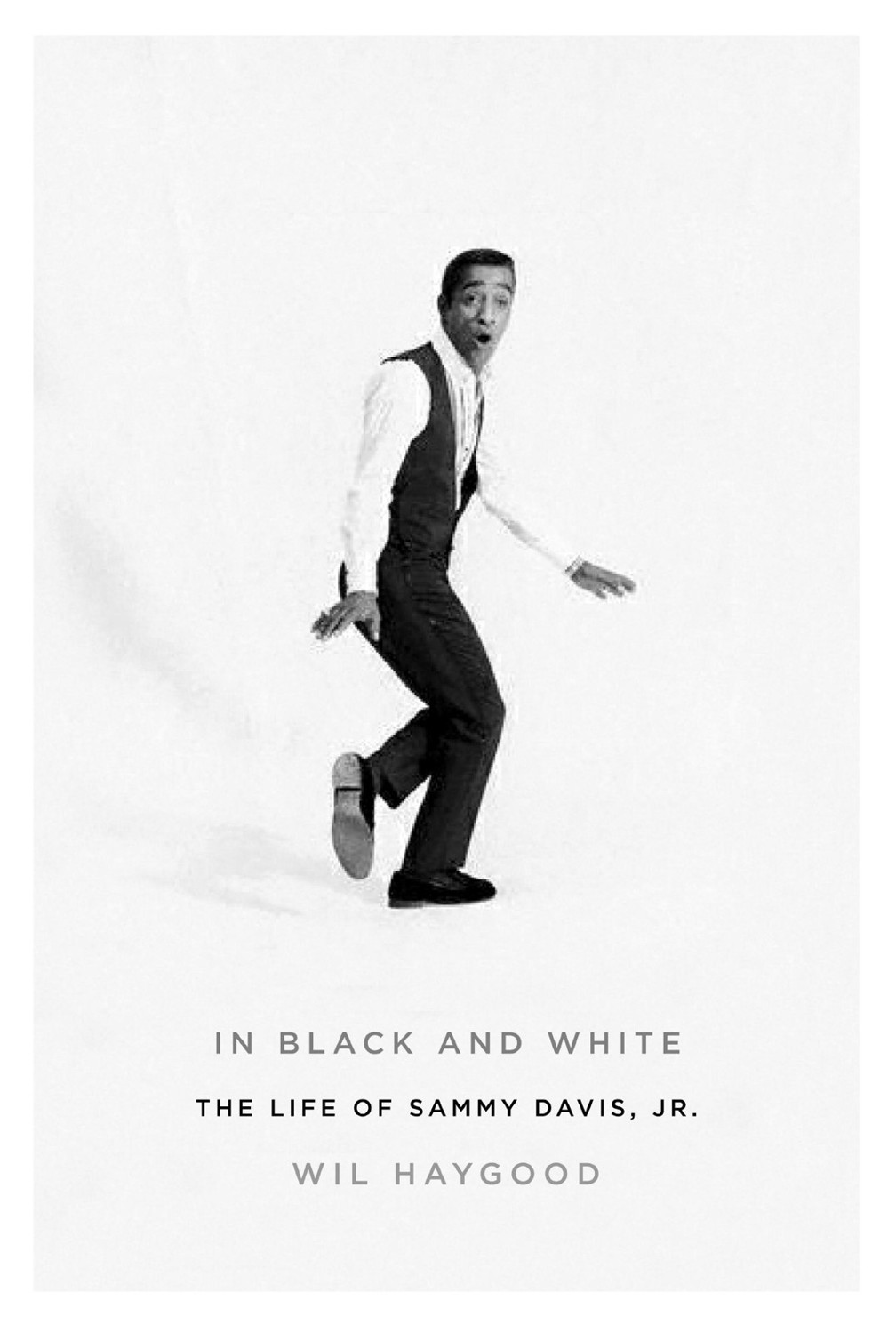

In Black and White: The Life of Sammy Davis Junior

Read In Black and White: The Life of Sammy Davis Junior Online

Authors: Wil Haygood

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #General, #Cultural Heritage

Two on the River

(photographs by Stan Grossfeld)

King of the Cats: The Life and Times of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr

.

The Haygoods of Columbus: A Family Memoir

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright © 2003 by Wil Haygood

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Portions of this work previously appeared in

Interview Magazine

and the

Washington Post Magazine

.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published matrial:

Aflred A. Knopf:

Excerpt from

The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes

by Langston Hughes. Copyright © 1994 by The Estate of Langston Hughes. Reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House Inc.

Hal Leonard Corporation:

Excerpt from the song lyric “Night Song” from

Golden Boy

words by Lee Adams, music by Charles Strouse. Copyright © 1964 (renewed) by Strada Music. Worldwide rights for Strada Music administered by Helene Blue Musique Ltd. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of the Hal Leonard Corporation.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN

0-375-40354-x

eBook ISBN: 978-0-8041-7252-3

v3.1

This book is dedicated to

Lynn Peterson

Marvelous tunes you rang

From passion, and death, and birth

,

You who had laughed and wept

On the warm, brown lap of the earth

.

Now in your untried hands

An instrument, terrible, new

,

Is thrust by a master who frowns

,

Demanding strange songs of you

.

God of the White and Black

,

Grant us great hearts on the way

That we may understand

Until you have learned to play

.

D

U

B

OSE

H

EYWARD

Porgy

YES HE CAN

B

y the ever twisting light of fame, he has lived a life both mesmerizing and distinctly peculiar. Since childhood he has wowed audiences across America as well as in many European locales. He is a veteran of nightclubs, radio, television, and film. Once the star of a trio dance act, for the past six years he has gone solo. There are many from the 1940s and 1950s who watched him grow up—onstage—and feel a kind of surrogate connection with him. His name often drops warmly from their lips. Like kin.

Sammy.

He has worked like a demon at familiarity. There have been a great many benefits for social causes. He’ll do anything for his pal Frank Sinatra. Likewise for Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. He won’t turn away from any Jewish cause, either. He works fifty weeks a year. He suffers from insomnia—not in the sense of a medical malady; he simply abhors sleeping, for there is so much on his mind, so many things he wants to do. He considers idleness a curse. Born of vaudeville, his peripatetic life has come to explode within the slippery parameters of the stardom he has chased ferociously for so many years. He has known it all: fear, pain, love, and hatred. Behind him lie thousands and thousands of motherless nights. He has learned to hoard his raging insecurities, for if onstage he is commanding and confident, offstage he carries a wobbly sense of self.

It is 1965, and Sammy Davis, Jr.’s America is afire. There are riots, marches, sit-ins. Assassins have come upon the land. No one blames him for the loaded pistol he carries. Or the umbrella he sometimes strolls with: it can be opened in an instant, exposing a knifelike point capable of inflicting a lethal wound. He is a Negro married to a white woman. The death threats are common. His booking agents rarely send him into the Deep South; he has a colossal fear he will be murdered in either Alabama or Mississippi. Whenever he travels, Joe Grant, his black-belt, karate-kicking bodyguard, accompanies him. But right

now, Sammy is ensconced on Broadway, starring in Clifford Odets’s

Golden Boy

at the Majestic Theatre. (Grant can sometimes be spotted in the theater basement, breaking wooden boards with his bare hands.) The lines are long for

Golden Boy

; the show is a smash. It is Sammy’s second turn as a Broadway star. This time around, Sammy is portraying a boxer, a fighter. Onstage he is also in love with a white woman. His stage name is Joe; hers is Lorna.

J

OE TO

L

ORNA

:

But you don’t know how I feel? Lorna, when I’m not with you I—bleed, I got a hole bleeding in my side nothing can stop but being with you because the other half is you, rotten, beautiful, the other half is you!—and I’m here on my feet, bleeding—for you—

It is, true enough, Odetsian stage speak, the rush of words and emotions and strange syntax, but it is also in some way a mirror of the times. America, having a bellwetherlike year, is herself constantly onstage. Every day there is an angry new protest, and new fears—in Selma, in Los Angeles, in Harlem. The bleeding occurs in a lot of places. Sammy himself is quite aware of the danger in the streets. He hates it when fans rush up to him on his left side. His left eye is sightless from a decade-old car crash, and he worries whether he might, in an instant, have to pull his gun. His heroes are cowboys, and he is extremely adept, as many in Hollywood know, at the quick draw. He has been known to dash off to Connecticut, home of Colt, the firearms maker, to have yet another set of guns—pearl-handled—made especially for him.

“Sammy and I wound up with the reputations of being the fastest draws in Hollywood,” says comedian Jerry Lewis, Sammy’s longtime friend, whom Sammy sometimes bested in mock showdowns. “And I was fast.”

“

Is his gun faster than Wyatt Earp’s?” a magazine article once asked of Sammy.

In his dressing room, in front of the mirror, he sometimes practices his quick draw. Two seconds: the hand snatching the gun out, then twirling it back into the holster. Two seconds. Don’t fuck with Sammy.

The big, wonderful, and edgy

Golden Boy

production—Sammy has already sent some of the proceeds down to Selma, to aid in “the movement”—suits him just fine, with its mixture of race and sex. With Sammy, there are always new dramas to battle old ones. And always a drama inside the ongoing drama, whatever it happens to be. Thunder in the soul delights him.

So: a twirling gun glints in a dressing-room mirror.

Draw!

Draw!

Draw!

But who is Sammy Davis, Jr.? What forces propelled him into being? How has he come to be proclaimed—by many, even in his own ego-ridden profession—“

the world’s greatest entertainer”? And why have there been so many motherless nights?

Eleven months into his

Golden Boy

run, Sammy’s autobiography was, at long last, ready for publication. The book—

Yes I Can: The Story of Sammy Davis Jr

.—had been more than five years in the making. An almost cultlike curiosity had grown around it. That the country was rife with turmoil could hardly stop the book’s publication now. But there lay, around the creation and publication of this book, hundreds of hidden little dramas. And those dramas, like much of Sammy’s life, veered from the comic to the tragic, from the sweetly sublime to the ashes of vaudeville. They illuminated Sammy’s ferocious determination in how he wished to present himself to the American reading public—a motherless Negro absent a culture, more white than black.

Yes I Can

was a stunning performance. And it was the making of that book—more than the book itself—that was a crystallization of everything Sammy had thus far mastered in life: shrewdness, guile, survival, fearless determination, and the switching of masks.

Yes I Can

had everything—except the real Sammy. As a

New York Times

reviewer would ask of the book: “

Can it be that it is now permissible to reveal everything except thought?”

The book’s beginnings date back to the late 1950s, in a series of Manhattan nightclubs, amid the jumpy voices and smoke and clinking of glasses. It began in the brain of Burt Boyar, Sammy’s new sidekick. They had first met when Sammy made his Broadway debut, in 1956, in

Mr. Wonderful

. Boyar, a newspaperman, wanted to write a book. Newspapermen were wont to dream of such things. Boyar’s book would be a novel. A novel about a Negro entertainer who rises to the top of the entertainment world. Included would be all the travails along the way, up and around the obstacle course that meandered through white and Negro America. For Boyar—dark-haired, handsome, tweedy—it would be fun, a thrill, an added hobby to life with his elegant and always fashionably attired wife. (Jane Feinstein met Burt in 1954, when she waltzed into his Madison Avenue press agent’s office. On their first date, while strolling down Fifth Avenue, he told her he was going to marry her. Two years after they were married, the Boyars met Sammy. So much about them intrigued him: not least that they were young and attractive. They were also Jewish, and Sammy, who had converted to Judaism, was shameless in his courting of Jews.)

The novel would be based on Sammy’s life, with Sammy as its hero. Burt and Jane did not consider themselves literary purists, by any means. They sometimes read Ayn Rand aloud to each other in bed at night, but that was for

fun. Their novel would be done quickly—they couldn’t imagine it taking more than a year. They’d just bang the thing out, have a romp with it.

Inside the nightclub on the evening they pitched the idea to him, Sammy listened as raptly as he did to any promotional idea that involved him. Which is to say he listened and, between interruptions, he half-listened, and between additional interruptions, he listened some more. There were so many schemes; they came and they went. While he listened, there went the quick jerk of the neck toward the door, following the new arrivals, Sammy waving maniacally, then the head yanking back to Burt, back to this book idea, the tapping of ash in the cigarette tray, the blowing of smoke, and then, a blonde, and another, all strolling by just to say hello, their perfume hanging in the air like bubbles.