Imperial Stars 1-The Stars at War (53 page)

One doesn't have to be a geographical genius to predict just who these people might be. That is, if they thought they could get away with it.

This decade is likely to present greater dangers to mankind than any since the end of World War II. If the Soviet Union succeeds in placing an operational laser battle station in orbit while the Americans fail to do the same, the free world will be at the mercy of its enemies, most of its strategic weapons rendered useless.

The reason is simple. A laser beam fired in the vacuum of space can, or will soon be able to, punch fist-sized holes in metal objects at a range of hundreds of miles. This means that American intercontinental ballistic missiles, which make some of their journey through space, could all be destroyed before they reach their targets.

Nor will Western missiles that travel to their targets without leaving the Earth's atmosphere, like the Cruise and the Lance, be necessarily safe from enemy battle stations in orbit. While the energy of laser beams can dissipate in air, especially on cloudy days, this is not true of weapons which shoot beams of charged particles.

Polaris submarines will soon be at risk from spy satellites. For many years they have been safe in the secret depths of the oceans, able to inflict more damage on the Soviet Union in the space of four minutes than Hitler did in four years. But this is unlikely to be true for much longer. The Russians have a large and growing fleet of space-borne anti-submarine satellites, with a developing ability to detect the infra-red "scar" which a submarine leaves on the surface, enabling them to track its movements.

In short, with space warfare, strategic weapons are entering a new realm of technology. Thanks to four inactive years during the Carter Administration, the Russians have gained a substantial advantage in their efforts to acquire the ability to destroy Western strategic forces totally and without warning. Unless America acts with determination, we may be faced in this decade with the choice between surrender or destruction.

Not being privy to the councils of the Pentagon, we cannot be sure whether the Americans are reacting to this crisis with sufficient speed and vigour. It is only possible to be certain of one thing: that the space shuttle, a quarter of whose flights will be military in purpose, will add enormously to America's ability to place weapons in orbit. And weapons there are needed above all else.

Only if the new Soviet threat is successfully countered can there be hope for continuing the mutual balance of terror, which has prevented war between the superpowers for more than 30 years, and which now is trembling so dangerously.

The old balance, consisting of thousands of missiles in their silos, will give way to dependence on electromagnetic weapons which move their targets, not at a cumbrous 17,000 mph, but at the speed of light, 670 million mph. This, like previous great advances in military technology, is likely to lead in turn to new social developments. Let us try to predict what they will be. The first consideration is that the existence of opposing laser battle stations in orbit, each holding the strategic forces of their client state in pawn, will not be the end of the cold war in space. Battle stations can themselves be attacked, and those weapons which threaten them will in turn be vulnerable to assault. The race will be on to construct the "ultimate" space weapon, a battle station so powerful and with such impregnable defences that all objects in low Earth orbit will be at its mercy.

One of the two safe places to install such a weapon will be beneath the surface of the moon. On the moon? At first sight, the idea must seem crazy, but it is being seriously considered as a long-term contingency plan by specialist groups at the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama, and at Strategic Air Command in Omaha, Nebraska.

Consider the advantages of a manned lunar laser battle station. The only remaining technical obstacle is the creation of a laser with sufficient power and narrowness of beam to destroy space vehicles at a range of 238,000 miles. But once installed it would be almost impossible to find, since it could be hidden anywhere among the moon's craters and canyons. It could not be destroyed by an opposing laser, since the enemy would not know where to fire. Nor could it be immobilized by a nuclear missile, since the approaching warhead would itself be vulnerable to the laser.

Building the station will, of course, require considerable preparations which can be observed by telescope. Would this reveal its intended location? Perhaps not. We speak now of a period 20 to 50 years hence, when civilian activity is likely to be taking place on the moon on a large scale. In this situation, military construction can be concealed. Peaceful technology is likely to follow the military lead into space, as it has in so many fields. As in the empires of old, the merchant will walk in the tracks of the army.

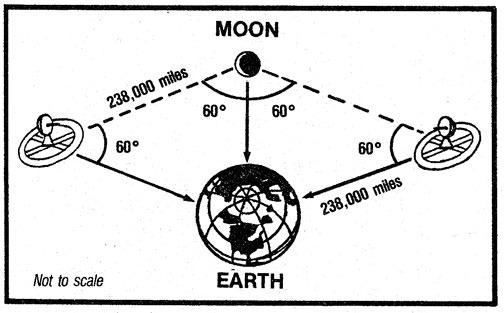

But the lunar battle station will have one disadvantage. It will only be effective in deterring aggression for about half the day. Anyone can verify, by playing with a small globe, that there are several missile flight-paths between Russia and key Western targets which, for some parts of the day, will not be in line of sight of the moon.

A Superpower desiring absolute command over the Earth would therefore need at least two more battle stations in deep space, so that all parts of low Earth orbit could be covered round the clock.

Where should they be placed? The ideal locations would be in two out of the four Lagrangian orbits.

Laser guns on the moon and in Lagrangian orbits.

Laser guns on the moon and in Lagrangian orbits.

The French Comte de Lagrange made in 1788 one of the few remarkable mathematical discoveries about the universe that took place between Newton and Einstein. Around two orbiting celestial bodies—in this case the Earth and moon—there are four points at which a third body could form an equilateral triangle with the other two, and remain there forever in stable orbit. The behavior of objects in these locations, would be influenced equally by the gravity of two worlds, providing stable vantage points for battle stations.

The pattern of war, and of preparations for war, may be extended ever more deeply into space in the distant future—with all man's activities—until the Earth itself ceases to be the target and the prize.

But whether we can survive to inhabit that distant future depends on decisions being made now; on recognizing that Earth-bound weapons will soon no longer deter aggression, and on deciding swiftly what to do about this fact.

That Share Of Glory

C. M. Kornbluth

Machiavelli has been accused on the one hand of killing political philosophy, and on the other of inventing the first science of politics. Here is James Burnham:

"Machiavelli's name does not rank in the noble company of scientists. In the common opinion of men, his name itself has become a term of reproach and dishonor . . .

"Why should this be? If our reference is to the views that Machiavelli in fact held, that he stated plainly, openly, and clearly in his writings, there is in the common opinion no truth at all. . . . It is true that he has taught tyrants, from almost his own days—Thomas Cromwell, for example, the lowborn Chancellor whom Henry VIII brought in to replace Thomas More when More refused to make his conscience a tool of his master's interests, was said to have a copy of Machiavelli always in his pocket; and in our time Mussolini wrote a college thesis on Machiavelli. But knowledge has a disturbing neutrality in this respect. We do not blame the research analyst who has solved the chemical mysteries of a poison because a murderer made use of his treatise . . ."We are, I think, and not only from the fate of Machiavelli's reputation, forced to conclude that men do not really want to know about themselves . . . Perhaps the full disclosure of what we really are and how we act is too violent a medicine.

"In any case, whatever may be the desires of most men, it is most certainly against the interests of the powerful that the truth should be known about political behavior. If the political truths stated by Machiavelli were widely known, the success of tyranny would become much less likely. If men understood as much of the mechanism of rule and privilege as Machiavelli understood, they would no longer be deceived into accepting that rule and privilege, and they would know what steps to take to overcome them.

"Therefore the powerful and their spokesmen—all the 'official' thinkers, the lawyers and philosophers and preachers and demagogues—must defame Machiavelli. Machiavelli says that rulers lie and break faith: this proves, they say, that he libels human nature, Machiavelli says that ambitious men struggle for power: he is apologizing for the opposition, the enemy, and trying to confuse you about us, who wish to lead you for your own good and welfare. Machiavelli says that you must keep strict watch over officials and subordinate them to the law: he is encouraging subversion and the loss of national unity. Machiavelli says that no man with power is to be trusted: you see that his aim is to smash all your faith and ideals."Small wonder that the powerful—in public—denounce Machiavelli. The powerful have long practice and much skill in sizing up their opposition. They can recognize an enemy who will never compromise, even when that enemy is so abstract as a body of ideas."

—

The Machiavellians

No one has ever built a social order on that kind of political science. No one in the real world. Here Cyril Kornbluth turns Machiavelli loose on the stars.

C. M. Kornbluth

Young Alen, one of a thousand in the huge refectory, ate absent-mindedly as the reader droned into the perfect silence of the hall. Today's lesson happened to be a word list of the Thetis VIII planet's sea-going folk.

"

Tlon

—a ship," droned the reader.

"

Rtlo

—some ships, number unknown.

"

Long

—some ships, number known, always modified by cardinal.

"

Ongr—

a ship in a collection of ships, always modifled by ordinal.

"

Ngrt

—the first ship in a collection of ships; an exception to

ongr

."

A lay brother tiptoed to Alen's side. "The Rector summons you," he whispered.

Alen had no time for panic, though that was the usual reaction to a summons from the Rector to a novice. He slipped from the refectory, stepped onto the northbound corridor, and stepped off at his cell, a minute later and a quarter mile farther on. Hastily, but meticulously, he changed from his drab habit to the heraldic robes in the cubicle with its simple stool, washstand, desk, and paperweight or two. Alen, a level-headed young fellow, was not aware that he had broken any section of the Order's complicated Rule, but he was aware that he could have done so without knowing it. It might, he thought, be the last time he would see the cell.

He cast a glance which he hoped would not be the final one over it; a glance which lingered a little fondly on the reel rack where were stowed: "Nicholson on Martian Verbs," "The New Oxford Venusian Dictionary," the ponderous six-reeler "Deutche-Ganymediche Konversasionslexikon" published long ago and far away in Leipzig. The later works were there, too: "The Tongues of the Galaxy—an Essay in Classification," "A Concise Grammar of Cephean," "The Self-Pronouncing Vegan II Dictionary"— scores of them, and, of course, the worn reel of old Machiavelli's "The Prince."

Enough of that! Alen combed out his small, neat beard and stepped onto the southbound corridor. He transferred to an eastbound at the next intersection and minutes later was before the Rector's lay secretary.

"You'd better review your Lyran irregulars," said the secretary disrespectfully. "There's a trader in there who's looking for a cheap herald on a swindling trip to Lyra VI." Thus unceremoniously did Alen learn that he was not to be ejected from the Order but that he was to be elevated to Journeyman. But as a Herald should, he betrayed no sign of his immense relief. He did, however, take the secretary's advice and sensibly reviewed his Lyran.

While he was in the midst of a declension which applied only to inanimate objects, the voice of the Rector—and what a mellow voice it was!—floated through the secretary's intercom.

"Admit the novice, Alen," said the Master Herald.

A final settling of his robes and the youth walked into the Rector's huge office, with the seal of the Order blazing in diamonds above his desk. There was a stranger present; presumably the trader—a black-bearded fellow whose rugged frame didn't carry his Vegan cloak with ease.

Said the Rector: "Novice, this is to be the crown of your toil if you are acceptable to—?" He courteously turned to the trader, who shrugged irritably.

"It's all one to me," growled the blackbeard. "Somebody cheap, somebody who knows the cant of the thievish Lyran gem peddlers, above all, somebody

at once

. Overhead is devouring my flesh day by day as the ship waits at the field. And when we are spaceborne, my imbecile crew will doubtless waste liter after priceless liter of my fuel. And when we land the swindling Lyrans will without doubt make my ruin complete by tricking me even out of the minute profit I hope to realize. Good Master Herald, let me have the infant cheap and I'll bid you good day."