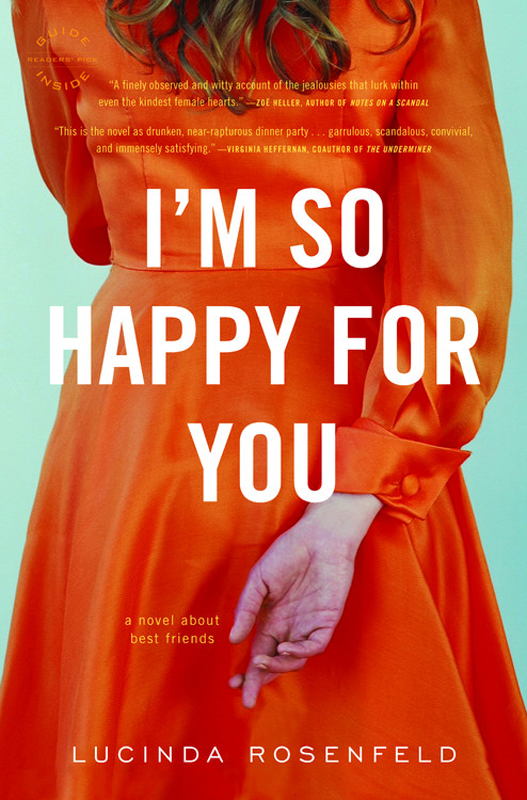

I'm So Happy for You

Read I'm So Happy for You Online

Authors: Lucinda Rosenfeld

Also by Lucinda Rosenfeld

W

HAT

S

HE

S

AW

…

W

HY

S

HE

W

ENT

H

OME

Copyright © 2009 by Lucinda Rosenfeld

Reading group guide copyright © 2009 by Lucinda Rosenfeld and Little, Brown and Company

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written

permission of the publisher.

Back Bay Books / Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: July 2009

Back Bay Books is an imprint of Little, Brown and Company. The Back Bay Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book

Group, Inc.

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and

not intended by the author.

ISBN: 978-0-316-07885-6

Contents

Questions and topics for discussion

Lucinda Rosenfeld’s friendship reading list

for the munches, senior and junior: jc, bc, and cc

Nothing fortifies friendship more than one

of two friends thinking himself superior to

the other.

H

ONORÉ DE

B

ALZAC,

Cousin Pons,

1848

S

INCE

W

ENDY

M

URMAN

had begun trying to conceive, eight months earlier, having sex with her husband, Adam Schwartz, had turned into something

resembling a military operation: spontaneity and passion were discouraged; timing and execution were everything. Late one

Sunday night, however, Adam, ignoring the calendar—it was day twenty-four of Wendy’s cycle—pressed up close against her in

bed and ran his right index finger along the elastic waistband of her underwear. Wendy’s first instinct was to tell him to

let her sleep and save his genetic material for the following week, but she didn’t want to offend him. She was also flattered

to think he was still so attracted to her.

Wendy was weighing her options when the phone rang in the living room. Pushing Adam away from her, she swung her legs over

the side of the bed and stood up.

“Can’t you just let the machine pick up?” Adam grumbled into his pillow.

“I’ll just be a minute,” Wendy said hurriedly on her way out the door.

The living room was pitch-black, and Wendy rammed her shin into the side of the coffee table. With one hand, and in agony,

she clutched her leg; with the other, she felt around for the receiver, which was still ringing. She finally located it on

the floor, sandwiched between the previous week’s issues of

The New Yorker

and

In Touch Weekly

. Earlier in the evening, she’d been reading a ten-thousand-word article about melting ice caps by Elizabeth Kolbert, only

to be distracted by a cover headline asserting that Jennifer Aniston was back on the dating market. Poor thing had apparently

been dumped again. Or at least according to

In Touch

she had been. “Hello?” she said.

“We-e-endy,” came the tremulous response.

Just as Wendy had suspected when she heard the phone ring, it was Daphne Uberoff, her best friend since college. Although

it was after midnight, Wendy wasn’t surprised to hear her voice. With every passing year, Daphne seemed to grow needier. Wendy

felt increasingly responsible for her mental and emotional well-being. She cared for Daphne; she also hated the idea of missing

some fresh drama in Daphne’s life. “Daf,” she said in the most compassionate tone of voice she could muster, “what’s going

on?”

“I’m sorry I’m calling so late.” Daphne followed her apology with a hiccuping sob reminiscent of bathwater being sucked down

the drain of an old tub. “But I’m not okay.”

“Is it Mitch?” asked Wendy. It was mostly a rhetorical question, since it was always Mitch, as in “Mitchell Kroker Reporting

Live from the Capital.” He was fifty, with the wrinkled and vaguely sulfurous complexion of a golden raisin. From what Wendy

could gather, Daphne saw more of him on TV than in real life. This was possibly due to the fact that, in addition to being

married to someone else (a weather-woman named Cheryl with immovable hair), he lived in D.C., while Daphne lived in New York.

“He called me when he got into town tonight.” Daphne was practically hyperventilating. “We were supposed to see each other,

but I was already feeling really frustrated because he was only going to be here for like a few hours”—audible inhale—“so

I said I felt like this hotel he checked in and out of, and he said he was sorry I felt that way, but he was giving me all

the time he had to give”—audible inhale—“so I said that wasn’t enough anymore and that I needed to know if this was leading

anywhere and he said”—choking sob—“he said that if I needed the promise of a commitment in the future, we shouldn’t see each

other anymore because he could never live with himself if he left the kids at least not until they’re out of the house which

will be in like two hundred years at which point I’ll be like TWO THOUSAND!” Daphne began to weep.

“Oh, Daf, I’m so sorry,” said Wendy, resisting the urge to point out the errors in Daphne’s arithmetic. “He’s such a fucking

disappointment!” She tried to sound impassioned both in her sympathy and her outrage. It wasn’t easy. Wendy had heard endless

variations of the same woeful tale before. Daphne had also asked her to interpret countless emails and voice messages from

Mitchell, none of which said anything of note. Wendy prided herself on being a good friend and knew that Daphne was going

through a rough time, but she’d grown impatient with her old friend’s steadfastness in the face of so much privation.

On rare occasions when Mitch was feeling romantic (i.e., immediately before sex), he’d tell Daphne that he fantasized about

the two of them running away to some beachfront bungalow on the Turks and Caicos Islands. Never once, however, had he offered

to leave his wife. Never once—as far as Wendy knew—had he even used the “L word” to describe his feelings for Daphne. From

what Wendy could tell, the only thing Mitchell Kroker had to offer was the prospect of sharing his suite at the Essex House

hotel, on Central Park South, every now and then when he happened to be in town.

It was also true that Wendy had grown weary of the story line and longed for a new character, a new development—anything to

advance the plot.

Her wish was granted shortly thereafter. But it wasn’t the plot point for which she’d hoped. “I feel like dousing myself with

gasoline and lighting a match,” Daphne announced through her tears.

“Daphne—take that back right now!” cried Wendy, even as she thought:

right

. She’d heard it all before. And before that, too. Daphne threatened to kill herself so often that her threats barely registered

with Wendy anymore—even as Daphne’s methods kept getting more grandiose. Once, she’d promised the mellow fade-out of pills.

Now she was pledging pyrotechnics.

“Why should I?” said Daphne, still weeping. “What good am I to anybody?”

“You’re good to a lot of people,” said Wendy, although she couldn’t think of anyone in particular.

“I’m going to be alone my whole life,” declared Daphne.

“That’s not true,” demurred Wendy. “Mitch is the one who’s going to be miserable and stuck in his awful marriage. And you’re

going to be madly in love with someone else. And then, I swear, you’re going to look back and wonder what you were ever doing

with the guy.”

“Wasting two years of my life,” Daphne said with a sniffle and a quick laugh.

To Wendy’s relief, the tears seemed to have dried up, at least for the moment. “Listen,” she said, “I want you to call Carol

tomorrow, as soon as you wake up.” Carol—as all of Daphne’s friends knew, since Daphne began so many of her sentences with

“Carol thinks”—was Daphne’s therapist. “And then, what about going to get a massage or something? I think you need to do something

nice for yourself right now.”

“The only thing I need right now is a new prescription for Klonopin,” said Daphne.

“Take a Klonopin if you have to,” said Wendy. “Just promise me you won’t take more than one.”

“I feel like swallowing the whole bottle —”

“Daphne!”

“What?”

“You’re scaring me again.”

“I’m not going to swallow the whole bottle. Okay?”

“Do you promise?”

“I promise!”

“Because you don’t need drugs. You just need to get rid of Mitch.”

“So I can sit here by myself feeling even worse?”

“Daphne, I swear, you’re going to be alone for, like, five seconds,” said Wendy, glancing at the clock on the cable box. It

was twenty to one. Her eye fell to the DVD player. She still missed her old VCR. Just when she’d finally learned to program

it—five years after purchasing—the technology had changed again. Plus, there had been something weirdly satisfying about the

buzzing noise it made when sucking videotapes into its gullet. Also, the new remote had four separate “play” buttons; who

had the energy to read another manual and find out why?

“Yeah, sure,” said Daphne.

“You don’t believe me, but I’m right,” said Wendy.

For several more minutes, the conversation continued in a similar vein, with Wendy offering sanguine prognoses regarding Daphne’s

future, and Daphne rebuffing them, even as her protests grew audibly weaker, possibly on account of the tranquilizer she’d

just swallowed.

By the time Wendy hung up, she felt assured that Daphne would do nothing more dangerous than fall fast asleep for the next

thirteen hours. Which was fine for her, Wendy thought. Daphne hadn’t had a real job since her midtwenties, when she’d been

an editorial assistant at a city listings magazine. Not that it had been a “real” real job. It had been Daphne’s responsibility

to “write up” the sample sales each week. (

X’s micro-weight cashmere separates will be 70 percent off retail.…

) These days, she filed “reader’s reports” for a small film production company—three or four times a year.

As Wendy contemplated Daphne’s schedule—or, really, lack thereof—she felt an old kernel of resentment rising to the surface

of her consciousness. Wendy was a senior editor at

Barricade,

a left-wing news biweekly that had been founded on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley in 1968 and relocated

to New York during the Reagan era. There was a movement afoot to transfer the whole operation onto the Web. But for the moment,

at least, the magazine was printed on the equivalent of developing-world airport toilet paper. It claimed a subscription base

of 90,000, every two weeks, though Wendy suspected that at least 40,000 of those were free subscriptions to public libraries

and extinct hippie communes. She also assumed that the only people who read

Barricade

already agreed with the editorials it ran (and she edited). But at least she was contributing to the dialogue.

Unlike Daphne, Wendy also woke up for work.

But then, other people’s good fortune didn’t necessarily exist at her expense. At least this is what Wendy had been encouraged

to believe by her own therapist—or, rather,

former

therapist—Marcia Meltzer, PhD, MSW, CSW. (Wendy had fired her after she raised her rates, then refused to continue submitting

bills to Wendy’s health maintenance organization, which reimbursed a modest but still significant 35 percent of Marcia’s fee.

There had also been tension between the two of them after friends invited Wendy and Adam away for a long weekend. Hoping not

to be charged for the missed session, Wendy had left a fraudulently rheumy message on Marcia’s answering machine, claiming

to have the flu. Marcia had charged her anyway.) Besides, Daphne’s good fortune didn’t currently extend very far, Wendy reminded

herself on her way back to the bedroom—despite the fact that Daphne’s HMO continued to cover 80 percent of the cost of seeing

Carol, which also seemed a little unfair.

“Sorry,” said Wendy.

Adam was sitting up in bed now, his reading light on and a free humor newspaper in his lap. (“Man Eats Sandwich,” read the

front-page headline.) No doubt he’d picked it up at the local coffee shop where he spent a substantial portion of his own

“workweek,” Wendy thought. A couple of months earlier, he’d quit his job as the copy chief of a respected financial news Web

site to write a screenplay. At the time, she’d been tempted to tell him that screenwriting was a skill like any other that

took years of practice, whereas he was just a novice. But she didn’t want to be the one to spoil his fantasies. He was her

husband, after all. She wanted to believe in him. And she was conflict avoidant. And he’d been bored with his job. And she

couldn’t exactly blame him for being so. How many more S’s could he be expected to add to the oft-misspelled “Dow Jones Industrials

Average”? So she’d agreed to support him for a year, during which time, in theory at least, he’d write a first draft.