I'm Just Here for the Food (34 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

When all of the meat had browned, I deglazed the bottom of the pan with ½ cup of the beer. It immediately came to a boil and I scraped the pan with a wooden spatula for a few moments until all of the stuck-on bits had dissolved. Everything left in the pan was added to the bowl holding the meat.

4:15 P.M.

Less than three hours to go. Most chili recipes require that long just to chop the ingredients. The actual cooking could take days, what with all that connective tissue to break down. Clearly, the pressure was on—heck, working under pressure had been the plan all along.

I broke out my heavy-duty 8-quart pressure cooker and poured in the salsa (16 ounces—I measured) and the rest of the beer (1 cup—again, I measured). Then I added the meat, along with all the juices that had accumulated at the bottom of the bowl. I stirred in a fat tablespoon of the tomato paste and then added 15 corn chips (did I mention these were the triangular kind?), which I broke to bits by pushing them down into the meaty melange with a wooden spoon.

4:18 P.M.

Lid on. I let the cooker come to full pressure over high heat, then backed off the heat until the steam dropped to a bare hiss and set the timer for 15 minutes.

4:33 P.M.

When the timer went off, I released the pressure valve and dumped the steam. (This always reminds of that scene at the end of

Alien

when Sigourney Weaver flushes the alien from its hiding spot on the shuttle.) I then added 1 tablespoon of chili powder, 1 teaspoon of ground cumin, 2 of the canned chipotles (chopped) along with 2 tablespoons of the accompanying adobo sauce. I stirred the whole thing, decided to add another handful of chips (the first load had disintegrated), lidded up, and brought the cooker back up to pressure for another 10 minutes. I then removed the cooker from the heat and allowed the pressure to abate on its own. When I removed the lid, the meat was fork tender and the sauce pleasantly spicy and thick.

7:00 P.M.

Back on my friend’s porch, I served the chili with a dollop of sour cream and chopped green onions and won the bet. Total bill (including the tomato paste I already had): $7.74.

28

CHAPTER 7

Brining

There are lots of ways to get flavor into food, but brining is the only way I know to season, enhance texture, and add weight to a piece of meat.

Have a Soak or Maybe a Rubdown

Like humans (or most of us), the words “marinade” and “brine” evolved from the sea: marinade’s root is marine, and brine’s—well, you know, briny deep and all that. Over time, marinade came to mean just about any flavorful liquid you soak a food in, and marinate came to mean the act of soaking a food in a flavorful liquid. Brine is both a noun and a verb: a salt solution and the act of soaking in said solution. It stands to reason, therefore, that while you can marinate a pork chop in a brine you can’t necessarily brine a pork chop in a marinade—unless, of course, that marinade is a brine. Got it? If you haven’t got time for a lengthy soak, try a quick rubdown—with spices, of course.

Marinades

Marinades have long been hailed as “tenderizers.” They’re not. Sure, acidic liquids (most if not all marinades contain an acid component such as vinegar, wine, or citrus juice) can dissolve proteins and even plant cellulose, but the effect is localized to the surface of the target food. Some food scientists even argue that the tenderizing effect doesn’t kick in until the meat crosses 140° F, but that’s not to say that marinating in the refrigerator is useless.

The reason that marinades

seem

to tenderize has more to do with flavor than any actual textural alterations. Most marinades contain salty, sweet, acidic, and spicy components. When these compounds are drawn into meat via capillary action,

29

they strongly season the meat. Then you cook it, slice it, and put it in your mouth. Immediately the salt and acid flavors divebomb your taste buds, which in turn tell your saliva glands to start pumping. By the time you’re onto your third chew your food is thoroughly lubricated, and since saliva contains enzymes like amylase, the meat is already well on its way to becoming an easy-to-digest goo. Marinades may not actually do much in the way of tenderizing meat, but their use does help

us

to tenderize it.

Brine

A brine is nothing more than a solution of salt and sugar dissolved in water. Although brines may contain other substances (alkaline phosphates are often added to commercial brines because pH is a factor in brine absorption), all that’s really required is salt and water.

Brines supercharge meats with flavor and moisture, and also can be used as a pickling agent for fruits and vegetables. Sauerkraut, for example, begins as little more than shredded cabbage and a weak brine that acts as a microbial bouncer, allowing the bacteria necessary for fermentation in, while keeping those that would spoil the party out.

FLAVORING AGENTS

Want to get more flavor into a piece of food before or during cooking? Choose your weapon:

•

Powder: Can be as simple as a sprinkling of salt and pepper or as complex as a dredging in a spice rub (See

The Rub

).

•

Breading or crust: Could be a standard breading (flour, egg, bread crumbs), a coating of crushed potato chips, or a crust of toasted nuts. The flavor comes not only from the added food but from the caramelization that results from its cooking. Crusts and breadings can also protect foods from overcooking. (Read the section on

breadings in Frying

.)

•

Baste: Any time you apply a flavorful liquid to a piece of food during cooking, you’re basting, and like the Force, basting can be used for good or evil. Grilling chicken thighs over an open fire: basting is good. Broiling your pork ribs after a long braise: basting is good. Roasting a turkey: basting is bad—very bad. My rule is that if you’re trying to cook a piece of food (especially meat) and you must open a door or lift a lid to get to it, you shouldn’t.

The No-Backyard Baby-Back Ribs

ribs are an exception because they’re already done. The broiling process is all about caramelizing the baste.

Had Shakespeare chosen to reach for a culinary metaphor in his love sonnets, brining would have been the one. Brining is a wonderful thing because it’s invisible. You brine a piece of meat, cook it, cut it, serve it, and everybody tastes it and exclaims in disbelief, “Man, this is great meat. You’re a genius!” Learn to brine pork and poultry and soon you’ll be clearing room on your mantel for that Nobel Prize in cooking. How can a simple concoction of salt and water make such a difference? Like most things, it’s a matter of chemistry.

Meat is made up of cells. Cells are surrounded by membranes, which function like borders between countries: they are discriminating. Any substance that wants in or out of the cell must present its papers and pass a rigid inspection. The substance that moves across this border most often and most freely is water.

The micromilieu of meat is all about balance. Inside the cell there are dissolved solids—salts, potassium, calcium, and the like—and outside there’s . . . well, it depends. Drop a pork chop in a bucket of distilled water and there’s nothing but H

2

O outside the border. In this case, the border officials are unhappy because there’s a lot more salt inside the cell than outside, thus no balance. So the border temporarily opens, and the guards allow some water to move into the meat and some salt to move out into the water. Eventually the meat will lose a good bit of its native flavor to the water.

However, if there’s salt in the water (even as little as a few hundred parts per million), the border guards—ever desirous of equilibrium—will throw open the borders and allow both salt and water to move across the membranes. Now this is where things get really interesting: after 8 to 24 hours there’s more salt in the meat, and more water has to be retained to balance it—that’s just the osmotic way. So now you’ve got cells that are perfectly seasoned with salt and nicely plump with water, which if you think about it is something of a paradox: salt pulls liquid out of meats, yet the right brine can pump water into meat.

But wait, there’s more.

SALAD DRESSING’S SECRET

When you whisk up a vinaigrette, make extra to use as a marinade. I like to use dressings containing either soy or Worcestershire sauce as marinades because their high sodium content acts like a brine.

Extra-virgin olive oil and commercial emulsifiers like polysorbate 80 also can help meat tissues absorb flavors. I usually keep some commercial salad dressings around even if I don’t use them on salads. The exception is French dressing, which I do keep around for salads. I can’t make French dressing because I don’t want to know what’s in it . . . ever.

BRINING AND MARINATING: THE SHORT FORM

•

Heavy zip-top freezer bags are great for marinating and brining because they allow for the most surface-to-marinade /brine contact. You can suck out the air before you seal the bag, and the bag itself provides the meat with an occasional massage, which helps the marinade or brine to be more quickly absorbed into the meat.

•

PH matters: the more acidic the brine, the longer the journey into the meat. So if your brine is heavy on wine or vinegar, consider adding some baking soda to neutralize the acid.

•

Temperature matters: meat proteins are more extractable around 34° F, meaning that the tissues in question will hold on to more water if brined at refrigerator temperatures.

•

Never wash off marinades or brines; simply pat the food dry before cooking.

•

Although marinated foods can be fished from the drink and wrapped for several days prior to cooking, try to time your soak session so that the brined food can go straight from the liquid to the heat. All those cells are puffed up like blimps, and without the counterpressure of the brine, the sheer weight of the food will begin to squeeze the brine out within minutes of leaving the bath.

•

When brining large items like turkeys or multiple pork shoulders, I put them in a plastic cooler and replace about a third of the brine liquid with ice.

•

Another good reason for brining and marinating at refrigerator temperature is, of course, sanitation. Most micro bugs don’t dig salty environs, but some don’t mind a bit.

•

A cure is simply a brine without the water. Since it’s pretty darned strong, it’s usually only used as part of a curing process, such as corning beef (the word cure is a reference to the size of the salt crystals used in the process) and making gravlax.

Like a molecular Trojan horse, the water can harbor other substances, specifically water-soluble flavors like brown sugar or various herbaceous elements whose flavors have been extracted via brewing. This means you can sneak various and sundry flavorings and seasonings into the meat.

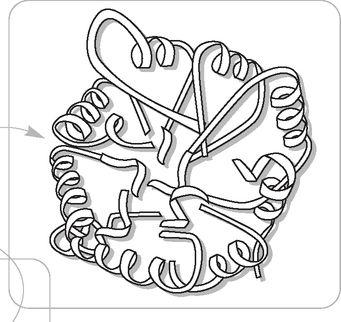

And yet there’s more. When salt gets into meat cells it runs into certain water-soluble proteins. They look sort of like this: