If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor (39 page)

Read If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor Online

Authors: Bruce Campbell

Tags: #Autobiography, #United States, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - General, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Actors, #Performing Arts, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - Actors & Actresses, #1958-, #History & Criticism, #Film & Video, #Bruce, #Motion picture actors and actr, #Film & Video - History & Criticism, #Campbell, #Motion picture actors and actresses - United States, #Film & Video - General, #Motion picture actors and actresses

Everyone was in place, waiting for their cue, but without warning, Sam's car crashed to the ground.

What was the deal? No signal had been given.

As we looked up toward the crane, it was evident that something was wrong. About this time, everything went into slow motion and Steven Spielberg took over as director of the scene.

The extended arm on the crane was wobbling more than it should -- this was for good reason, because the support legs holding the crane in place had given out and it was slowly falling off the cliff.

The crew watched helplessly as this gigantic machine crashed to the bottom of the gravel pit. Unbeknownst to us, a man was on the cliff side of the rig as it gave way. With reflexes born of adversity, he ducked under the truck as it tipped over and was spared a horrific fate.

These are the times when "make believe" and reality meet head-on -- the rest of the day was a wash. Ironically, after all the hassle, we wound up using the footage from 1986.

Events like this and the effort to make the film we wanted to make took their toll on our budget. To get our funding from $8 million to $11 million, Rob, Sam and I agreed to personally put up the contingency (totaling about a million dollars) in case we went over budget.

By the time we finished principal photography, the money had trickled through our fingers like a fine desert sand. Something was terribly wrong with this scenario: this was part three of a successful string of films -- weren't we supposed to

make

money off this film?

ACTING BY THE NUMBERS

After six weeks in the desert, we settled in for months of studio work. Sam Raimi continued his undisputed reign as master of the technical nightmare -- this time, he reduced me to acting by numbers, literally, through a process called Introvision. It was one of the few instances where the old cliché, "It's all done with mirrors," really applied -- mirrors were part of this front-screen projection process.

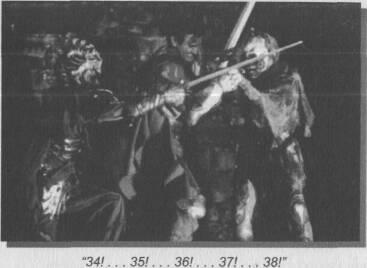

"Thirty-four, thirty-five, thirty-six, thirty-seven, thirty-eight..." Those numbers barked out via megaphone by an effects assistant all correlated with specific movements of an animated skeleton that I had to interact with -- in this case, during a sword fight.

At #34, I had to arrive at a critical mark on the floor. At #35, I'd turn toward a specific spot on the rear screen since I couldn't actually see the skeleton. At #36, I'd duck a swipe from the skeleton, and as I rose, a live-action puppet skeleton attacked me from behind. I'd have about 2.5 seconds to fend him off before #40, when I'd take a swing at the animated skeleton. By #42, the beast would be defeated and I'd be off to the next fight. Notes from a director for scenes like this take on a bizarre twist.

Sam: Bruce, thirty-eight wasn't right. It was late.

Bruce: I know, I was still thinking about thirty-six. But, I think I nailed forty.

Sam: Yeah, that was better -- and you've got more time before forty-two... maybe a second.

Bruce: Okay... no sweat.

SLICE AND DICE

Shooting came to a halt in the fall of 1991 and the process of editing several hundred thousand feet of film began. During this, I began to witness the negative effects of making, for lack of a better description, a "dumbbell" film.

A film like

Army

is very hard to defend -- the plot is simple-minded and the narrative drive is wrapped around a series of action sequences. Witness, if you will, an editing room conversation:

Dino: Six skeletons blowing up is too much. Three is all you need.

Rob: No, Dino, we've got to have six!

Pino: Why?

Bruce: Because we... because... we

need

them?

Dino: I'll send the footage to you. Cut them out...

This haggling went on through the test screening process. According to test audiences,

Army

was too long, and the end, where Ash wakes up in a postapocalyptic world, was too "depressing."

I'm sure by now, you can guess the outcome. Sam's original director's cut was ninety-six minutes long. Fifteen minutes of battle footage, most of it financed by us, was removed. The new studio version with a "happy" ending was eighty-one minutes.

The only saving grace of shooting a new beginning and ending was that Bridget Fonda was involved. She had been a fan of the series and asked for a small role. What were we gonna say, "No"?

36

ANATOMY OF A PAYCHECK

We all hear about how much money actors make. Admittedly, some earn more for a single job than the gross national product of small countries, but I would like to offer a little perspective.

Let's say that you starred in and coproduced

Army of Darkness.

This was a second sequel, and by all accounts, you're entitled to earn a little moola for your efforts.

Just to pick a figure out of the air, let's start with $500,000 -- a king's ransom. Now get your calculators out and stay with me. First thing you do is subtract twenty-five percent of that amount to cover agents and managers -- $125,000. That leaves you with a whopping $375,000.

Okay, before you buy that big house, slice that figure in half -- between federal and state taxes, all at the highest rate, and someone to prepare a more complex tax return, you're left with $187,500. That was fast, wasn't it?

But wait, there's more -- if you had been divorced just prior to

Army,

your ex would be entitled to half of the take from that film. After taxes that's $93,750, and it leaves you with the same amount.

You're thinking, "That's still some serious coin!" I couldn't agree more, but between a long production schedule and studio squabbling,

Army

took two years to complete, so crunch those numbers again and divide by two -- that leaves you with $46,875 a year. You, too, can become a rich movie star.

37

LONG LIVE THE "HUD"

Near the end of

Army,

I announced to Sam Raimi, "I hope that's all you have to shoot, pal, because I'm off to work on a

real

film!" Of course, Sam knew what I was talking about -- he had cowritten the Coen Brothers' industrial fantasy,

The Hudsucker Proxy.

In theory, the film wasn't all that different than our dud

Crimewave,

except for the fact that the Coen Brothers had ten times the money and big-shot actors in their pocket.

I was contacted to audition for the part of the wisecracking newsroom reporter, Smitty. For the first time in a long while, I had to stop and think about it. I auditioned for a bit part in

Barton Fink,

but didn't get the role, and I had just finished

Army of Darkness

for a major studio. Granted,

Army

was a genre flick, destined to become a college drinking game, but a line in the sand had to be drawn -- my history with the Coens spanned more than a decade.

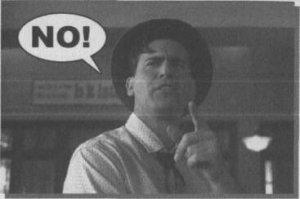

Revelation #48:

"No" is the most powerful word in the Hollywood dictionary.

I decided to say no. I would gladly and willingly accept the role, but these fellows knew my work well enough to spare me the audition.

No.

Use the word wisely, and it can be liberating -- use it a lot and you'll starve. In this case, it worked because I was offered the role, minus an audition. This may seem trivial, but to an actor it means

everything --

it is the difference between crawling through glass and being carried on pillows.

That said, I was thrilled to be a part of this classy production. John Cameron was the assistant director of the film, so it was a comfortable setup. The Coens asked me to join their two-week rehearsal process, reading the miscellaneous roles that needed a voice. I jumped at the chance because it was a return to "fly-on-the-wall" status.

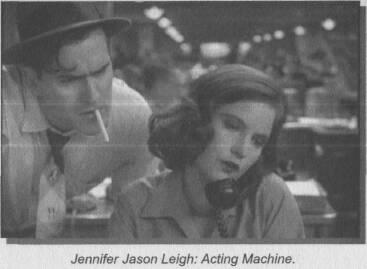

That first rehearsal was a heady experience -- one by one, they came through the door: Jennifer Jason Leigh, Tim Robbins, and eventually,

P-P-Paul N-N-Newman.

No more low-budget stuff for me,

I thought.

Time to cross

Maniac Cop

off the resumé!

Another of my duties during this time was to run lines with the actors any time they wanted. When Paul Newman took me up on the offer one day, I wasn't sure whether to jump for joy or barf, because I was both elated and terrified.

As we sat in his trailer preparing to read a scene, my first goal was to make sure not to piss him off by doing something stupid.

Bruce: So, uh, Mr. Newman --

Paul: Call me Paul.

Bruce: Okay, sure. So, uh,

Paul,

when we run these lines, how picky do you want me to be?

Paul: What do you mean?

Bruce: Well, do you want me to correct you a lot, a little, or not at all?

Paul: Tell you what, I just need to stumble through this first -- how about if I call out for the line if I need it?

Bruce: Okay -- you got it...

Paul: It's funny, I used to have a mind like a steel trap. Then, one summer a long time ago, I did eighteen different plays in twenty-four weeks and it all turned to mush...

The two weeks of rehearsals were also a good time to get fitted for my costume. Normally, on the low-budget stuff I had done, I'd give my sizes to the costume designer over the phone and hope for the best. Not so on

Hudsucker --

Richard Hornung was a designer who really did it right.

I only had a small role, but when I showed up for the fitting, I never saw more clothes in my life. Richard and I began with a discussion about colors -- he felt that my character should start in lighter colors, then go a little darker when my character gets creepier. I hadn't even thought of that, but it sounded good to me.