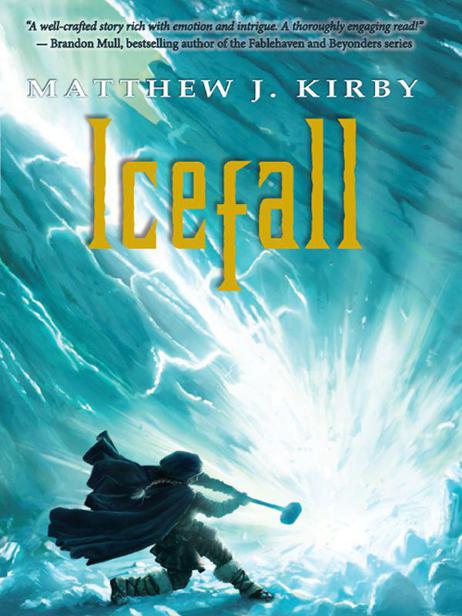

Icefall

Authors: Matthew J. Kirby

FOR AZURE

Chapter 22:

THE BREAKING OF THE WORLD

Listen to me. For I have many stories to tell….

T

he fjord is freezing over. I watch it from the edge of the cliff near our hall, and each day the ice claims more of the narrow winding of ocean. It squeezes out the waves and the blue-black water, while it squeezes us in. Just as Father intended it to. Winter is here to wall us up, to bury us in snow and keep us safe.

Today, there is a cold wind that bears no other smell but the ghostly scent of frost. I feel it through my furs and woolen dress, down to my skin. My younger brother, Harald, stands beside me, watching the cloud of his own breath.

“Do you think they will come today, Solveig?” he asks me.

“They will arrive soon,” I say. “Father said they would.”

“I hope so.” He turns to walk off. “The larder is nearly empty.” And he whistles.

Harald is a stubborn, willful child, full of confidence and mischief. He reaches the earthen walls that surround our hall, and the warriors who guard the entrance bow to him. He stops to talk with them, and I can see in their affectionate smiles that they love him even now, their future lord. He will make a strong warrior, and a fine king one day, so long as Father still has a kingdom to pass on.

All of the sky looks like a burnt log in the morning hearth, cold, spent, and ashen. Harald is right. I have noticed our helpings at the supper bench getting smaller, how Bera does not cook so great a quantity as she always did at home in Father’s hall. We didn’t bring enough provisions with us to last a whole winter here. But there was so little time for preparation before Father sent us away and went to war. He promised a boatload of food, clothing, and blankets, but we have seen no ship.

And none today.

And the fjord is freezing over.

I leave the cliff, pass through the gate, and nod to the guards. Inside, the hall is dim and smoky. Asa, my older sister, sits shivering near the fire in the center of the room. She looks up for a moment when I enter, her eyes and cheeks red, and looks away again as though she did not see me. She does not eat much, and does not sleep much, and never comes outside with me or Harald anymore. I miss the way it used to be between us. I do not know where her joy has gone, but her beauty remains, her skin like new cream, her golden hair.

I wish that I had her grace, but I am plain, and Father’s eyes do not shine with pride when he looks on me. I would gladly go to war, bearing spear and shield beside my king, were I to have the strength I see in Harald. But Father does not laugh and boast of me the way he does his son and heir.

I am only Solveig.

We have been here for several weeks, having left our home at the end of harvest-time just as the farmers were bringing in the last of the barley and wheat and butchering the livestock too weak to survive the winter. We will miss the celebration for Winter Nights, something Harald has complained about loudly, so I told him stories of the Wild Hunt as we sat by the fire and ate our cheese curd drizzled with honey.

But in the span of these last few weeks, we’ve fallen into a kind of rhythm, whether we want to or not, and I have taken to helping out around the steading, including the milking of Hilda, our one goat.

Harald leans against the cowshed’s doorpost, rolling a bit of straw between his teeth as he watches me. Hilda casts me a defeated glance as I wring what milk I can from her droopy teat. She is the only livestock we managed to bring with us, and she is drying up. We did not bring enough food for her, either. During the day, she wanders the yard or lies in the shed we use as a byre, but at night she sleeps in the hall near the hearth, as we have no other animals to keep her warm.

Sometimes, when Asa’s sleep is restless, I leave the bedcloset and lie next to Hilda, my cheek against her winter coat.

“Why are you doing servants’ work?” Harald asks.

A strand of hair crosses my face, and I blow it away. “Bera and her son have enough to do. Besides, it does me good.” I tug a little too hard on Hilda, and she shies away from me. “You could stand to take on a share of the chores as well.”

Harald laughs his easy laugh. “Have you not seen me practicing with the guards every day?”

“Will your wooden sword feed us, then?”

“No.” He holds the needle of straw before him like a blade. “But if father’s enemies find us, you’ll all be glad I learned to fight.”

He slashes the air, and I shake my head, grinning. “Perhaps we will.”

Harald parries and stabs a few more times, and then chuckles at himself. Then he is silent a moment. “Perhaps I should help out more with the chores. Maybe go fishing with Ole. Things are different here.”

I give up on Hilda’s udder and stand with the nearly empty bucket. I don’t know what we’ll do without milk for sour skyr, curd, and cheese. We rely on those to see us through the winter. The nanny goat shakes her head, relieved, and I turn away from the thought that we may have to slaughter her for meat.

“Things are very different here,” I say. “I’m going to take this to Bera.”

He steps aside and lets me pass through the door. The milk rolls around the bottom of the bucket as I cross the yard. Our hall is situated in the wedge at the end of the fjord, flanked by tall mountains to the north and south. The hills to the south are covered in soft pine, while the rocky crags to the north march above us like a procession of trolls, a party out hunting for human daughters to carry away in the night as stolen brides.

I find Bera in the hall, at the hearth, stirring a stew. Her hips are broad, her gray hair braided and gathered in a thick knot at the base of her neck. She has served my father since I was a child, and raised me after my mother died giving birth to Harald.

She hears me approach. “Hilda still giving us anything?”

“Not for much longer,” I say.

I hand her the bucket and she peers at its contents. “Hmph. But at least the old goat tries.” She glances at Asa, who lies on a bench against the wall, staring at the ceiling.

“Is there anything else I can help with?” I ask.

“Raudi’s trying to dig the last of the carrots out of the ground.”

“I can help with that.”

“Ground is near frozen.”

“I know,” I say, and leave Bera cooking in the hall. Asa doesn’t move, and in a moment of frustration with her, I shut the hall doors a little too hard behind me.

The feel of coming snow waits in the air like the inhale before a sigh. I walk around to the vegetable patches in back, the remnants left from the harvest ruined with frost. Raudi kneels on the hard ground, hacking with a pick. A few frozen carrots, lumpy and misshapen from too much time in the ground, lie in a basket by his side. They’re the same rusty color as his hair.

I drop down beside him. “Can I help?”

He keeps digging.

“Raudi?”

“I suppose.”

I grab another pick and choose a spot farther down the row of browned tufts. We work in silence, and within a few minutes, I feel a rim of sweat on my brow in spite of the cold. Raudi and I used to be friends, though he is a winter older than me. We often swam and ran and played together, but then his older brother died in battle, and Raudi decided that he needed to spend his time with boys and men. I tried to understand. It is the way of things. And even though he started walking taller and talking louder, we still smiled at each other as we passed in the yard.

But ever since we came here, he has grown aloof and curt with me. Never openly disrespectful, but never friendly. I feel his absence like a dull ache, even though he’s right here, working only a few feet away from me.

My carrots come out of the earth looking like half people, with legs and arms and other appendages. After we’ve pulled

up the last of them, we rise to our feet and take them to the larder, a shed with a turf roof, built mostly underground. We set the carrots in the darkness next to the few turnips and onions, and return to the hall for the night meal.

Harald is already there, waiting with his wooden bowl and bone spoon. Old Ole sits next to him, mending a fishing net. Bera sings a song over the kettle as Raudi and I take our places. Moments later, our three warriors march into the hall. Two of them, Egill and Gunnarr, I do not know well, but I know the kindest and handsomest. His name is Per. The three of them sit down at a slight distance the way they always do, outside the circle of family and servants. Harald would like to sit with them, I am sure, but chooses to remain with us. Raudi takes a bench between the warriors and the rest of us, not really sitting with either group. Asa rises and drifts across the room to her seat near me, and we’re all gathered. All the members of our household.

We eat the stew of fish and pork, with golden pearls of fat glistening over the surface, and it is delicious because Bera made it. But there isn’t much of it, and we’re all wiping out our bowls with stale bread before long. After that, the men drink some ale, and we sit together in the descending night.

A banging at the door draws Gunnarr, the gray-haired oldest soldier, from his bench. “Blasted goat,” he mutters. When he opens the door, Hilda prances into the hall. She shakes her horns, bleats, and then settles down in the straw on the floor. But then she looks at me, and gets up and comes over to lie

down at my feet. I like that she has come to prefer me, and I smile.

Per clears his throat. “The fjord will be closed off before long.” He looks around the room, his blond hair and dark blue eyes soaking up some of the firelight.

No one says anything at first.

“What is your point?” Ole asks without looking up from his net. He is a thrall, a slave captured in war many years before I was born. He has seen much of the world, or claims to, and has come to love my father as his king.

“Ships won’t be able to reach us,” Per says.

“They’ll come before it closes,” Ole says. He has been with us for so long, he can say things that other thralls can’t.

Per glances toward Asa, and she looks back at him, and something passes between them. Some silent communication, and I wonder what it means. I have always liked Per. As the second daughter, and the plain one, most of the time I feel like people only notice me and bow because they have to. But not with Per. When he bows to me, and smiles his broad smile, I feel that he really sees me, and that he means it.

Raudi leans toward Per. “How soon until it freezes over, do you think?”

“Hard to know,” he says. “A week. Two, maybe.”

“They’ll come,” Ole says again.

Raudi looks at his lap and mumbles, “We shouldn’t even be here.”

“Silence,” Bera says to her son.

And then it occurs to me, the reason for Raudi’s ill temper. He blames my family. If it wasn’t for us, he and his mother would be safe at home. But because of us, they are both imprisoned in this forgotten place, threatened with starvation or worse if we’re found by my father’s enemies. So he broods over the hot coals in the hearth as if they are the embers of his anger, and they are glowing red. I want back the boy I knew.

“I’m sorry, Raudi,” I say, but he only stares.

A week passes, and the fjord is still open, barely. From the vantage of the cliff, the way inward from the sea is but a stray black thread fallen from a loom. So long as it stays that way, Ole can fish without having to break through the ice.

He wants to slaughter Hilda, but I won’t let him, even though she eats our food without giving a single drop of milk in return. I have grown fond of her, and only when we are starving, and when there are no fish left in the sea, will I let Ole take his knife to her throat. I know that is foolish and wrong of me.

But a boat

will

come.

Harald and Per are sparring in the yard, and Harald holds a wooden shield. The day is overcast and dim, our hours with the sun diminishing with the season. Snow drifts through the air like dust, landing cold on my cheeks and refusing to settle

to the ground, which is still bare and frozen. Harald shifts from foot to foot as Per waves a blade.

“Don’t try to stop the blow directly,” the warrior says. “That’ll shatter the shield and take your arm.”

“Then what should I do?” Harald asks.

“You need to move with the strike, use the shield to glance it away from you.”

He brings the sword down slowly enough for Harald to get his shield under it.

“Which way am I striking?” Per asks.

Harald grunts. “To the left.”

“Then sweep my blade to the left.”

Harald heaves the shield to the side, and with it Per’s sword point.

“Good.” Per steps back. “Again. Faster, my little prince.”

“I’m not little.”

Per laughs, and when he laughs it’s from his belly. He is tall and strong, his hair pulled back with a bit of yarn, his leather armor oiled and well kept. In spite of his reputation for prowess in war, there is a mirth about him when he is at home. Not like some warriors. Some men never really leave the battlefield, and if they do, they bring the ghosts of the dead back with them. Like Father when he falls into one of his black moods.