ICAP 2 - The Hidden Gallery (7 page)

Read ICAP 2 - The Hidden Gallery Online

Authors: Maryrose Wood

If so, Penelope theorized, and if Lady Constance were not so terribly spoiled but had instead had the benefit of a more Swanburne-like education, she might well turn out to be a perfectly pleasant companion. She and Penelope might even be friends, were it not for the vast difference in their social stations, what with Lady Constance being a lady and Penelope being a lowly governess.

“Dear me, that is a lot of âifs' and âmight have beens,'” Penelope concluded. “But still, there is no harm in offering a friendly greeting. Today she will be tired from her long journey, but perhaps tomorrow, after I have done with the children's lessons for the day, I will go downstairs on some pretext or other and see if I can engage Lady Constance in pleasant conversation. It would be the kind and generous thingâthe Swanburne thingâto do.”

A

WELL-KNOWN POET

â

not Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who wrote “The Wreck of the Hesperus,” a poem with which the Incorrigible children were already quite familiar, but a different poet, named Robert Burnsâonce wrote a poem called, simply, “To a Mouse.”

Now, you might find this title silly and even a bit misleading, for what famous poet writes poems to mice? Especially when there are so many shipwrecks, headless horsemen, gloomy talking birds, and other

equally fascinating topics to write poems about?

On the other hand, perhaps Mr. Burns was using his poetic license. This is the license that allows poets to say things that are not precisely true without being accused of telling lies. Anyone may obtain such a license, but still, the powers it grants must be wielded responsibly. (A word to the wise: When asked, “Who put the empty milk carton back in the refrigerator?” if you reply, “My incorrigible sister, Lavinia,” when in fact it is you who are the guilty party, at the ensuing trial, the judge will not be impressed to hear you defend yourself by claiming that your whopper was merely “poetic license.”)

However, the title “To a Mouse” is not an example of poetic license, for the poem was, in fact, written to a mouse, which simply goes to prove that one never knows from what furry little rodent inspiration will strike. In Mr. Burns's case, inspiration struck the poet soon after his plow struck the nest of a “wee beastie,” which is to say, a small field mouse, and tore it all to pieces. His eight-stanza apology includes the memorable lines:

The best-laid schemes o' mice an' men

Gang aft agleyâ¦

It should be pointed out that the poem is written in an old Scottish dialect, and thus contains words that are rarely used nowadays, even in Scotland. To “gang aft agley” means to “often go astray.” What Mr. Burns was driving at was this: The mouse, who had built herself a cozy nest and was no doubt feeling quite smug about it, was now flat out of luck, and that is simply the way life goes, not only for mice but for people, too. One thing is planned, and yet something quite different actually occurs. A careless poet accidentally plows your mouse house to bits, an important appointment is missed due to a flat tire on one's velocipede, or a well-intended and perfectly friendly overture is interpreted as something else altogether.

Thus it was the next day, when Penelope eventually went downstairs to strike up a conversation with Lady Constance. Her impulse to offer some fellowship was a kind and noble one, and yet it was received in an entirely different spiritâfor one of the disadvantages of having a postal delivery five times daily is that it creates so many opportunities to be disappointed when a much-longed-for invitation fails, and fails, and fails yet again, to arrive.

The morning post had brought nothing to the house but the day's newspaper. The midday post had brought an advertisement promoting the skills of a

local chimney sweep. Now it was nearly three o'clock, and another post was due any moment. It was Margaret's duty to await the postman by the front door, silver letter tray in hand.

As was always the case at mail time, there were two sharp raps on the knocker, after which the mail came sliding through a brass mail slot in the lower part of the heavy wooden door.

Knock! Knock!

“Is it the post?” Lady Constance's voice rang eagerly down the stairs.

“Yes, my lady, butâ”

“The post! The post!” Lady Constance clattered down two flights at a dangerous pace. She ran so fast her hair came undone and popped up in yellow curlicues all 'round her head. “The afternoon post, at last! For this morning I sent word to all my acquaintances in town saying that I had arrived. I expect to be

buried

in luncheon invitations, and dinner parties, too, of course, and asked on all manner of excursionsâMargaret, remind me to tell Mrs. Clarke: We ought to offer a small gratuity to the postman; his mailbag is bound to be extra heavy for the duration of our stay in Londonâ”

But there was nothing on Margaret's tray except a brochure for Dr. Phelps's Miracle Cream: “Guaranteed

to Remove Wrinkles, Spots, Warts, and Lumps!”

The drama would be played out again at five o'clock, and finally at eight. By that point Lady Constance was in a foul mood; the lack of correspondence seemed to be taking a dreadful toll on her already delicate constitution. She refused her supper and instead demanded a particular type of marzipan that Mrs. Clarke had to send the young houseboy, Jasper, scurrying all over London to find. Then she very nearly scalded herself in the newfangled bathtub, and had to be lifted out red faced and yelling by two terrified ladies' maids.

Lord Fredrick had scarcely been home at all (“Business, dear,” he had explained as he rushed out the door right after breakfast). In short, Lady Constance was on her very last nerve, and the final post of the day was due in exactly one and one-half minutes.

Alas, it was at this very moment, after the Incorrigibles had been tucked into their beds, that Penelope came downstairs. The intention to show a bit of warmth to her mistress was still firmly lodged in her mind. She knew nothing about Lady Constance's postal disappointments, since she herself had been happily occupied all day, strolling the parks of London while studying latitude and longitude with the children. This was at Alexander's request; he was quite taken with the

topic of navigation all of a sudden and refused to go ten steps in any direction without referring to his compass. And the children had showed admirable restraint when it came to both squirrels and pigeons; Penelope had only had to offer a few cautionary reminders and the occasional distracting biscuit.

Yes, Penelope was in quite a different mood than poor Lady Constance, for the very notion of navigation made her think of Simon, and the thought of Simon made her giddyâgiddy enough to be idly whistling the same lilting sea chantey that Simon himself was prone to whistle when taking a reading on his sextant, as she skipped lightly down the stairs. And Penelope, too, was half expecting a letter, for she had written to Simon in that morning's post inquiring about the Gypsy woman. Might a reply be on its way already? Clearly, in London, anything was possible.

“Good evening, Lady Constance,” she called out cheerfully when she spotted the lady standing next to Margaret at the front door. “Welcome to Muffinshire Lane! Isn't London marvelous?”

Lady Constance turned, and Penelope saw that her usually perfectly dressed and coiffed mistress was, to be kind, a wreck: Her cheeks were scalded, her hair was frizzed, and her eyes were puffy and ringed

'round with dark, exhausted circles, like those of a raccoon.

“I fail to see what is so marvelous, Miss Lumley,” she snapped. Then she spun back to Margaret and began desperately wringing her hands.

“This is the last post of the day, is it not?”

“Yes, my lady, butâ”

“Why is it so

late

?”

Margaret swallowed anxiously. “It has not yet struck eight o'clock, my lady. I am sure he will be here soonâ”

Knock! Knock!

There were the two raps on the door. Penelope watched, puzzled, as Lady Constance gasped and clutched at her throat. Margaret stood in readiness as a single, elegant envelope poked through the slot and dropped noiselessly on the tray.

“Finally!” Lady Constance shrieked. “Is that it? There is only the one?”

“Yes, my lady, butâ”

“Let me have it, please.”

“Yes, my lady, butâ”

Terror had reduced Margaret to a single phrase, yet no matter how many times she uttered it, Lady Constance paid her no mind.

“Let me have it right now, or I will take it myself!”

Lady Constance hurled herself forward to snatch the letter.

“Butâit's for Miss Lumley, m'lady,” Margaret squeaked. She curtsied low, and extended the tray to Penelope.

The grim silence as Penelope gingerly descended the bottom step, walked five paces forward, and took the lovely cream-colored envelope from Margaret's tray was broken only by the

cuckoo-cuckoo-cuckoo

of a grandfather clock in the hall, striking the hour. That meant Lady Constance had eight full

cuckoos

to build up a head of steam. She used the time well, and when the eighth cuckoo was done, she let loose.

“Miss Lumley, do my eyes deceive me? This is the most impertinent thing I have ever heard of!”

“Perhaps it's from the same gentleman who wrote to you yesterday,” Margaret squeaked in a confidential tone. Alas, it was not confidential enough. Lady Constance took a menacing step toward Penelope.

“Yesterday? Do you mean to tell me that youâa mere governess!âhave received

two

separate pieces of correspondence since arriving in London, while I have received

none whatsoever

?”

“I do apologize, Lady Constance.” Penelope keenly wanted to glance at the envelope to see if it was, in

fact, from Simon, but she dared not in front of Lady Constance, who looked as if she might tear it to shreds with her teeth. “It was not my intention to receive any letters. They simplyâ¦arrived.”

And then, perhaps unwisely, she added, “Do you know that poem by Mr. Robert Burns, called âTo a Mouse'? I was just reading it to the children before bedtime. It makes rather the same point, about things not happening in the way we expect. âThe best-laid plans of mice and menâ'”

But, much as she would have liked to, Penelope did not get to pronounce “gang aft agley,” because Lady Constance was not listening. “Humph!” Lady Constance said, speechless with fury. She said it again. “Humph!” Then she stormed back upstairs to her lavishly decorated but friendless suite of rooms, leaving Penelope and Margaret staring at their shoes, at least until Lady Constance was well out of sight.

Then, without risking any animated conversation, exclamations of delight, or other audible signs of happiness that might provoke their mistress further, Margaret simply handed Penelope the silver letter opener, which had been lying unused all day on the tray. Her expression of intense, agonizing curiosity said the rest, as did the excited way she pranced in place

and the soundless giggles that she carefully muffled with her free hand.

But the letter was not from Simon at all. It was a reply from Miss Charlotte Mortimer! Once she realized that, Penelope was even happier than she had been before, though it was a different sort of happy.

Happy, that is, until she read the letter.

Â

My dear Penny,

I am so relieved to hear that you and the children made it to London without incident. Did the

Hixby's Guide

lead the way?

Please join me for luncheon tomorrow, in the Fern Court at the Piazza Hotel. Though I long to meet your three pupils, and plan to do so at the earliest safe opportunity, for now it is best that we talk alone. I have news, not all of it good, and none of it for children's ears.

I ask that you keep the time and place of our meeting to yourself. I shall be there at twelve sharp; look for me by the Osmunda regalis.

Do be careful.

Yours as ever,

Miss Charlotte Mortimer

G

IVEN THAT FERNS ARE NOT

nearly as popular as they once were, you can hardly be expected to know that

Osmunda regalis

is the scientific name of the much-admired royal fern. It is a truly spectacular variety that can easily grow six feet tall, with arching, attractively shaped fronds and spore-bearing stalks that turn a pleasing shade of brown when fully mature.

The spore-bearing stalks are called “sporangia.” Many would no doubt argue that “sporangia” is hardly a word worth memorizing, yet one never knows when

ferns will make a comeback. The forward-thinking among you would do well to jot it down.

Sadly, the Piazza Hotel has long since been demolished to make way for the sorts of retail establishments that people seem to prefer nowadays: boutiques selling new clothes that have been made to look worn, banks that have run out of money, and cafés that brew coffee so strong as to be virtually undrinkable. But on the long-ago day that Miss Penelope Lumley was scheduled to dine with Miss Charlotte Mortimer, the Fern Court at the Piazza Hotel was in its prime. Its magnificent display of potted ferns was famous throughout Europe, as was its mouthwatering and inventive cuisine, courtesy of the legendary Chef Philippe, a true master of the cutting board.

Under normal circumstances, Penelope would have been surprised that the usually no-frills Miss Mortimer had chosen such an elegant restaurant for their meeting. She would have been thrilled at the prospect of seeing an important collection of ferns, and even felt some anticipatory tummy rumbles at the thought of eating what promised to be a truly delicious meal.

However, just as a carelessly spilled puddle of India ink blots out the line of practice cursive letters painstakingly written on the paper beneath, the

anxiety-producing contents of Miss Mortimer's letter blotted out any other emotions Penelope may have had. What did Miss Mortimer mean, that it was not “safe” to bring the children? And that she had bad news to deliver? And that Penelope should tell no one about their meeting?

A chance encounter with a pickpocket on a train, a greedy scoundrel in front of Buckingham Palace, a strange remark from a fortune-teller, a mistress in high dudgeonâthese were life's minor annoyances, and Penelope knew better than to make too much of them. But Miss Mortimer's letter seemed to imply that there was actual trouble afoot. What on earth could it be?

All these worries and more swirled through Penelope's mind as she dressed for this long-awaited reunion. She briefly considered putting on the fine gray dress that she had worn to the Ashton Place holiday ball, but just thinking about the disastrous consequences of that night made her slip on one of her usual brown woolen frocks instead.

She took deep breaths to calm herself, as all the girls at Swanburne were taught to do in a class called Do Not Panic: A Swanburne Girl Always Keeps Her Wits About Her. After a few inhales through the nose and exhales through the mouth, Penelope felt that

her wits were, if not directly about her, at least within arm's reach.

“Since I have never eaten in a fancy restaurant before, the experience is bound to be educational,” she thought, with a renewed sense of purpose. “In any case, the only way to find out what Miss Mortimer has to say is to go and hear it for myself. Dear Miss Mortimer! I hope she is not too changed, after all these months.”

And so, with her eagerness to see her former headmistress only slightly dimmed by worry, and after obtaining assurances from Margaret that she would keep a close eye on the children while Penelope was out (since Penelope was forbidden to tell where she was going, her evasive reply that she would be “having lunch with a friend” simply made Margaret giggle and squeal about Simon Harley-Dickinson all the more), Penelope double-checked the map, put on her best hatâwhich is to say, her only hatâand set off for the Piazza Hotel.

Â

“Y

OUR TABLE IS THIS WAY,

Miss Regalis.”

Try as she might, Penelope had not been able to make the maître d' at the Fern Court understand that the reservation was not under the

name

Osmunda

Regalis, but that she was intending to meet someone

near

the

Osmunda regalis

. Still, she knew he was leading her in the right direction, for even among so many magnificent varieties the

regalis

were impossible to miss. The many potted specimens created a jungled grotto on the far side of the dining room, and the diners within, if any, were well concealed by the delicately swaying fronds.

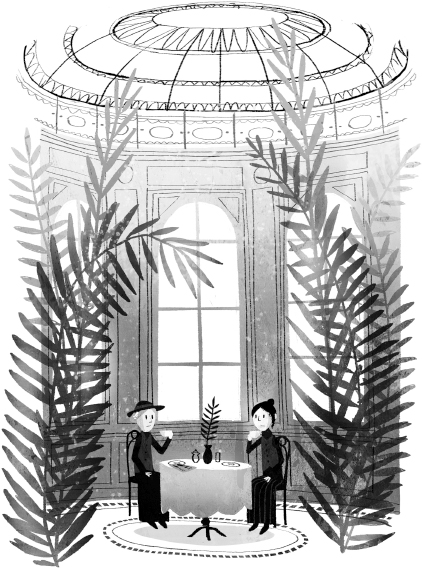

Penelope wondered if it was a desire for secrecy that had prompted Miss Mortimer's choice of restaurant, and not just an appreciation for fernsâbut she did not have to wonder for long. With a flourish, the maître d' held back an armful of foliage so that Penelope could enter the leafy, secluded room. There, at a charming table for two, with her only companion being the thin plume of steam that rose lazily from the teapot before her, sat Miss Charlotte Mortimer.

Changed or unchanged, bad news or good, it no longer mattered. The mere sight of her former headmistress, with her long, dark blond hair pulled back in its familiar pretty chignon at the base of her neck and her graceful, perfectly upright posture on display even as she sat reading the newspaper (as Agatha Swanburne once said, “To be kept waiting is unfortunate, but to be kept waiting with nothing interesting to

read is a tragedy of Greek proportions”)âwhy, it was all Penelope could do not to break into a run and hurl herself into Miss Mortimer's lap, just as she used to do as a child.

“But she is no longer my headmistress; now we are colleagues and friends,” she reminded herself. “I must restrain myself from acting like a schoolgirl, for those days are behind me.” And with that, she smiled, extended her hand, and spoke. “Miss Mortimer! How nice it is to see you!”

“Penny, dear Penny!” Ignoring Penelope's offer of a handshake, Miss Mortimer flew to her feet and hugged her former student tightly. When she finally pulled away, her eyes glistened.

“It is wonderful to see you, too, my dear. It has been much, much too long. But you are always in my thoughts, believe me.” Her smile was so tender, and the feeling in her voice was so warm and genuine, that Penelope felt all her newfound professionalism melt into a puddle. How silly she had been to think that time, distance, or anything else would ever alter her friendship with Miss Mortimer!

The kind headmistress gestured for Penelope to sit. “I hope you do not mind; I have already ordered lunch for us both. The food here is just as good as people say,

but you absolutely must save room for dessertâdear me, Penny! How grown-up you look! You have become quite pretty, did you know that?”

This unexpected compliment threw Penelope for a loop. “Ohâoh, my!” she stammered. “Really, Miss Mortimerâ¦I hardly think soâ¦the light here among the ferns must be rather dimâ¦.”

“I assure you, I can see perfectly well. Even your hair has changedâ¦.” Miss Mortimer frowned. “I think you have not been using the Swanburne hair poultice, as I asked you to do; am I right? Well, we shall discuss that shortly.” She unfolded her crisp white napkin and placed it neatly across her lap. “Forgive me for asking, Penny, but I must know: While you are here with me, are the children being attended to?”

“Of course.” Penelope carefully imitated Miss Mortimer's actions regarding the napkin. “There is a young housemaid named Margaret, one of the staff from Ashton Place who has accompanied the family to London. She is watching them during my absence.”

“I see. And this Margaretâis she trustworthy?”

“She is young, and can be silly at times.” Penelope remembered the giddy way Margaret had teased her about Simon. “I suspect she may not be a very good housemaid; Mrs. Clarke is always scolding her about

this and that. But when it comes to the well-being of the children: Yes, she is completely trustworthy.”

“I am glad to hear it.” Miss Mortimer's serious expression softened. “Patient Penelope! I know you must be full of questions, and yet you sit there so calmly, as if nothing I might tell you could rattle your confidence. I admire your courage more than I can say. You do the Swanburne Academy proud.”

Penelope murmured humble thanks, but inside she was beamingâand increasingly curious.

“In my letter, I said I had some news for you. But first I must hear about the children.” Miss Mortimer leaned forward and lowered her voice, though they were the only diners in this hidden grotto. “Do they ever speak of their days in the forest? Does Alexander, in particular, remember anything of a time that may have come before?”

“They have not mentioned anything to me about it.” Penelope spoke in a similarly hushed tone, since it would have felt awkward to answer in any other manner. “But it is obvious from the way they behave that they spent their time in the company of wild animals. Despite their academic accomplishments, they remain very fond of howling and are prone to chasing small, edible creatures. And Beowulf does

tend to chew. Especially shoes.”

“How fascinating.” Miss Mortimer sat back and sipped her tea. “Tell me more.”

“They can be provoked by other things as well.” Like any proud teacher Penelope loved nothing more than to talk about her students. “Why, just the other day, our trip to Buckingham Palace was cut short when the children mistook one of the palace guards for a bear. It caused quite a commotion.”

Miss Mortimer began to laugh. “A bear!” she exclaimed. “Why? Because of the hat? Oh, that is priceless!”

Miss Mortimer's unexpected reaction jolted Penelope into a useful change of perspective: That terrifying business with the guard was nothing more than a funny escapade, really! Why had she not seen it that way before?

“Yes, it was quite a comedy,” she said, laughing along with Miss Mortimer. “Beowulf actually climbed on top of the guard's head!”

“His head? Oh, my!”

Now the two of them were so merry that Penelope could barely finish the story; she was too busy gasping for air. “And Cassiopeiaâ¦tried to biteâ¦his leg!”

“Ha ha ha ha!” Miss Mortimer had to wipe tears of mirth from the corner of her eye with the napkin.

“We had another hilarious mix-up, too, with a Gypsy fortune-teller!” Penelope went on in the same jovial spirit, for if one unpleasant episode could be made into an amusing anecdote, why not all of them? “Oh, the children were distraught! They howled up a storm, and later kept repeating some odd words the woman said to them: âThe hunt is on.' Ha ha ha ha!”

It took Penelope a few seconds to realize that Miss Mortimer had stopped laughing. Not only that. The expression on her face had altered in a way that made Penelope feel chilled to the bone.

“âThe hunt is on?'” Miss Mortimer whispered. Her eyes darted around, as if she were worried someone might be eavesdropping. “Are you sure that is what she said?”

“That is what the children told me.” Now all of Penelope's worry came rushing back at once, like a tidal wave, and the questions poured out: “Miss Mortimer, why does that disturb you so? Why was it not safe for the children to come to lunch? What is the bad news you have for me?”

Miss Mortimer opened her mouth to reply, but at that very moment the most mouthwatering aroma Penelope

had ever smelled in her life wafted over to their table.

It was their first course, being wheeled through the ferns on a cart. Penelope and Miss Mortimer sat in awestruck silence as the waiter uncovered their appetizer plates. Penelope could not tell what it was. But the smell! It was positively scrumptious.

Miss Mortimer inhaled appreciatively, picked up her fork, and took a slow, savoring bite. “Fiddleheads Philippe,” she said. “Try it. You will be amazed.”

“Fiddleheads?”

“Ferns,” Miss Mortimer explained. “The curly tips of unfurled fern fronds. It makes an excellent tongue twister, doesn't it? Unfurled fern fronds! Unfurled fern fronds!”

Only after Penelope had mastered saying “unfurled fern fronds,” tasted the fiddleheads Philippe, and admitted that they were beyond her wildest imaginings of deliciousness, did Miss Mortimer begin to answer her questions.

“The hunt is on,” she repeated, shaking her head. “It is remarkable that you should have been given such a warning, but nothing surprises me anymore. Penelope, the bad news is simply this: The children are in danger, even more so now than when they lived in the forest.”

“What kind of danger?” Penelope exclaimed. “Why? From what source?”

Miss Mortimer paused and stared at her plate for a moment, as if some other, happier pronouncement might yet reveal itself there. “There is someone who wishes them ill, but he will notâhe cannotâharm them directly. However, he will do whatever he can to put them in danger's path. You have already seen evidence of this.”

“You mean, at the holiday ball?”

The headmistress nodded. “When I received your letter some months ago, telling me of the strange events of that evening, my suspicions were aroused. After much reflection I thought I would share my concerns with you. I wanted to do it in person; it is why I asked you to come to London. But this warning from the fortune-teller confirms it. Penelope, do you believe in the supernatural?”

Penelope took another bite, for no conversation, however disturbing, could ruin a dish this tasty. “Certainly not. But I did hear Lady Constance say once that Ashton Place must be cursed.”

Miss Mortimer was so startled she almost dropped her fork. “She was complaining about how long the repairs were taking,” Penelope quickly explained. “It

was only a metaphor, I am sure! But why do you ask? Surely you do not put any stock in curses and crystal balls and such, do you?”