I Think You'll Find It's a Bit More Complicated Than That (35 page)

Read I Think You'll Find It's a Bit More Complicated Than That Online

Authors: Ben Goldacre

If these symptoms were caused by electromagnetic signals, then it should prove possible to study that, ideally in double-blind conditions. The media coverage invariably focuses on the scandal of how research into this area has been neglected: but in fact, dozens of double-blind studies have been performed. A typical experiment involves a mobile phone or wireless network device, hidden in a bag or box. Each subject – chosen from people who report that their symptoms are caused by electromagnetic signals – records their symptoms over time, without knowing if the phone is on or off.

There have now been thirty-seven

1

such double-blind

‘provocation studies’ published

in the academic literature, and they are almost all negative. Seven studies did find some statistically significant effect for electromagnetic signals: but for two of those, even the original authors have been unable to replicate the results; for the next three, the results seem to be statistical artefacts (they either use one-tailed t-tests, which assume that the effect can only be negative, and so lower the bar of proof either way; or they make multiple comparisons without accounting for that in the analysis); and for the final two, the positive results are mutually inconsistent (one shows worsened mood with provocation, and the other shows improved mood, which makes the one-tailed t-tests in other studies seem even less reasonable).

These studies test the very claim being repeatedly made in the media: that symptoms are brought on by exposure to a source of electromagnetic signals, and cease when the source is removed. Mostly they are ignored. A recent

Panorama

documentary on BBC 1, covering the possible dangers of wi-fi computer networks, went further. A large chunk of the programme was devoted to electrosensitivity, and the programme-makers followed someone into a lab at Essex University, where they had participated in a provocation study. We were told that this subject correctly identified when the signal was present or absent two thirds of the time, against a visual backdrop of laboratory equipment.

But this was anecdote, dressed up as data. The study is currently unpublished. We don’t know the protocol, or whether 2/3 for one subject would be statistically significant (there may have been only three exposures in total, for example). We don’t know the results of other subjects. But most crucially, there is no mention that this single selected subject – in a single unpublished study – produced a result that seems to conflict with a literature of thirty-seven studies which are completed, published and, overall, negative. Even if this whole Essex study was positive – which seems unlikely – that would still need to be put in context with the dozens of negative findings that exist already.

Why doesn’t the media ever mention this data? Perhaps they deliberately leave it out. Perhaps they never came across it, and are incompetent. Or perhaps they simply lifted their stories verbatim, from aggressive and well-coordinated lobbyists, who promote this new diagnosis and, in many cases, sell expensive equipment to sufferers.

There may also be a darker side. Electrosensitivity lobbyists are not simply silent on the provocation studies: many of them launch vicious attacks on anyone who dares to mention this data, saying they are insensitive, that they are attacking sufferers, and – crucially – that they are denying the reality of patients’ symptoms. Symptoms, of course, stand as real, regardless of their cause; and if anyone is inflicting harm, it may be those who obfuscate on the causes. It takes bravery, but we can only develop better treatments through better understanding.

Guardian

, 19 August 2006

Sometimes you know an academic paper has overplayed its hand just from the title. ‘Deconstructing the Evidence-Based Discourse in Health Sciences: Truth, Power and Fascism’– from the current

International

Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare

– is one such paper. Even Rik Mayall in

The Young Ones

might pull back from using the word ‘fascist’ – or derivatives of it – twenty-eight times in six pages.

Initially I thought it might be a spoof. After all, who could forget the Sokal hoax, where a Professor of Physics at NYU submitted ‘Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Physics’ to

Social Text

, the leading postmodernist academic journal. This deliberately meaningless joke article – purporting to undermine the entire discipline of physics – was accepted and published, to universal delight.

But this new article is very real. Here’s what the authors put in the ‘objectives’ section of their abstract: ‘The philosophical work of Deleuze and Guattari proves to be useful in showing how health sciences are colonised (territorialised) by an all-encompassing scientific research paradigm – that of post-positivism – but also and foremost in showing the process by which a dominant ideology comes to exclude alternative forms of knowledge, therefore acting as a fascist structure.’

If I can put my fascist cards on the table, these are not ‘objectives’. Setting details aside, here is a quote from their authority figure, French philosopher Félix Guattari, to illustrate the clarity of his thinking: ‘We can clearly see that there is no bi-univocal correspondence between linear signifying links or archi-writing, depending on the author, and this multireferential, multi-dimensional machinic catalysis.’ And from Gilles Deleuze: ‘In the first place, singularities-events correspond to heterogeneous series which are organized into a system which is neither stable nor unstable [Jesus], but rather “metastable”, endowed with a potential energy wherein the differences between series are distributed.’

These characters are being recruited to attack the notion of evidence-based medicine, and the argument of this paper – it’s not an easy read – seems to be that: evidence-based medicine rejects anything that isn’t a randomised control trial (which is untrue); the Cochrane Library, for some reason, is the chief architect of this project; and lastly, that this constitutes fascism, in some meaning of the word the authors enjoy, twenty-eight times.

Here’s a flavour: ‘The classification of scientific evidence as proposed by the Cochrane Group [sic] obeys a fascist logic. This “regime of truth” ostracises those with “deviant” forms of knowledge. When the pluralism of free speech is extinguished, speech as such is no longer meaningful; what follows is terror, a totalitarian violence.’ They make repeated allusions to Newspeak. At one point they seem to identify epidemiologists with George W. Bush.

Now, firstly, they are plain wrong about the Cochrane Library, an organisation which simply produces systematic reviews of the published medical literature: Cochrane doesn’t only use trial data, in fact many Cochrane reviews contain no trials at all. This is pure ignorance.

But there is a more important general issue here. Evidence-based medicine is often portrayed – especially by ageing professors from the dying era of eminence-based medicine – as soulless and algorithmic. But that is a foolish caricature. EBM, in all the key textbooks, from the earliest editorials, is about using quantitative information alongside all other forms of knowledge: taking account of clinical judgement, and patients’ wishes, and boring things like the availability of local services. It does not denigrate other forms of knowledge, like clinical experience or patient preference: it seeks to augment and inform them. EBM is not about being an automaton.

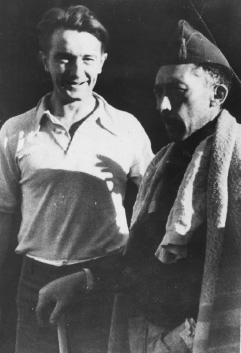

That’s all a bit sensible. How about some more childish attacks, ideally involving fascism? OK, then. I will wear their label of ‘fascist’ with a cheeky grin. But Archie Cochrane, on the other hand – pioneering epidemiologist, and inspiration for the Cochrane Library – might see things a little differently. After the war, and after working on miners’ lung disease, he helped to inspire a democratising culture shift towards evidence-based practice throughout the whole of medicine, and as a consequence, he has probably saved more lives than any single doctor you know. Before that, he was a prisoner of war for four years in Nazi Germany (‘The main reason for my capture was my inability to swim to Egypt’). And before that, in 1936, he dropped out of medical school and travelled to Spain to join the International Brigade, where he fought genuinely violent totalitarian oppression, the fascists of General Franco, with his own two hands.

Archie Cochrane (left) as a captain in the International Brigade, c.1936.

Now. What did you do

in your summer holidays

?

Guardian

, 9 July 2011

Since I was a teenager, whenever I have a pivotal life event coming – an exam, or an interview – I perform a ritual. I sit cross-legged on the floor, and I imagine an enormous golden beam of energy coming out of my arse.

I picture this anal beam passing through each layer beneath me: through the kitchen of the flat below, through the shop and its basement, past gas pipes and sewers and then deep into the earth, where it spreads out into a glorious branching root network, sucking power from the earth. I picture this energy surging through me; I visualise the outcome I want, in enormous detail; and I will it to happen, for about five minutes.

Surprisingly enough, this nonsense is broadly supported by data from randomised controlled trials.

One example was published

last month. About two hundred students were randomly assigned to four groups, each with activities supposed to increase their fruit intake. The control group just repeated their goal to themselves (‘Eat more fruit’). Another group concentrated on elaborate mental images of themselves enjoying fruit. The third repeated verbal plans for specific situations (‘When I see fruit, I will …’). The last group visualised elaborate scenes of encountering fruit, picking it up, touching it, eating it.

Among participants eating lots of fruit already, four portions a day, there wasn’t much change in their subsequent habits. Among people eating less fruit to begin with, one and a half portions a day, everyone increased their intake; but the ones performing the most elaborate mental imagery did so much more (their intake doubled).

It’s not a perfect study – I don’t like

subgroup analyses

for a start, and it only followed up participants for seven days – but it’s not alone.

An earlier study

from 2009 randomly assigned a hundred students either to a control group or to a couple of forms of imagery, picturing themselves choosing a healthy snack over an unhealthy one. The imagery group went on to have more healthy snacks.

Meanwhile, a meta-analysis from 2006 collectively analyses the results of ninety-four studies and finds that ‘implementation intentions’ (‘If I am in situation X, I will do Y’) had a positive effect overall on goal achievement.

So there’s probably something there, and this research tells us some interesting things about science. Firstly, I think this kind of research is useful. Rupert Sheldrake is the researcher who claims dogs can sense their owner is coming home before they arrive. I disagree with him on a lot, but he has one great idea: that each year, a proportion of the research budget – a hundredth, a thousandth – should be spent on whatever the public vote for. Most of it would go on MMR and

homeopathy

, of course, but some of it might go on testing, revising and improving stuff that improves people’s everyday lives.

Secondly, it shows us that even if you’re wrong about how something works, it might still work. I was sold the golden-bum-beam stuff with a lot of nonsense about quantum hippy energy, but I’ve always thought of it as a perfectly sensible way to combat distractibility. Effective things can come from silly places.

Guardian

, 4 December 2010

Why do clever people believe stupid things? It’s difficult to make sense of the world from our own small atoms of experience, and a new paper in the

British Journal of

Psychology

this month shows how we can create illusions of causality, much like visual illusions, if we manipulate the clues and cues.

These researchers took 108 students and split them into two groups. Both were told about a fictional disease called ‘Lindsay Syndrome’, that could potentially be treated with something called ‘Batarim’. Then they were told about a hundred patients, slowly, one by one, hearing each time whether the patient got Batarim or not, and whether they got better.

When you’re hearing about patients one at a time, in a dreary monotone, it’s hard to piece together an overall picture of whether a treatment works (this is one reason why, in evidence-based medicine, ‘expert opinion’ is ranked as the least helpful form of information). So, while I can tell you that overall 80 per cent of these imaginary patients got better, regardless of whether they got Batarim or not (the drug didn’t work) that isn’t how it appeared to the participants. They overestimated its benefits, as you might expect; but the extent to which they overestimated its effectiveness depended on how the information was presented.