I Think You'll Find It's a Bit More Complicated Than That (27 page)

Read I Think You'll Find It's a Bit More Complicated Than That Online

Authors: Ben Goldacre

In fact, most doctors participate in research by playing a small role in a larger research project which is coordinated, for example, through a research network. Many GPs are happy to help out on a research: they recruit participants from among their patients; they deliver whichever of two commonly used treatments has been randomly assigned to their patient; and they share medical information for follow-up data. But they get involved by putting their name down with the Primary Care Research Network covering their area. Researchers interested in running a randomised trial in GP patients then go to the Research Network, and find GPs to work with.

This system represents a kind of ‘dating service’ for practitioners and researchers. Creating similar networks in education would help join up the enthusiasm that many teachers have for research that improves practice with researchers, who can sometimes struggle to find schools willing to participate in good-quality research. This kind of two-way exchange between researchers and teachers also helps the teacher-researchers of the future to learn more about the nuts and bolts of running a trial; and it helps to keep researchers out of their ivory towers, focusing more on what matters most to teachers.

In the background, for academics, there is much more to be said on details. We need, I think, academic funders who listen to teachers, and focus on commissioning research that helps us learn what works best to improve outcomes. We need academics with quantitative research skills from outside traditional academic education departments – economists, demographers, and more – to come in and share their skills more often, in a multidisciplinary fashion. We need more expert collaboration with Clinical Trials Units, to ensure that common pitfalls in randomised trial design are avoided; we may also need – eventually − Education Trials Units, helping to support good-quality research throughout the country.

But just as this issue stretches way beyond a few individual research projects, it also goes way beyond anything that one single player can achieve. We are describing the creation of a whole ecosystem from nothing. Whether or not it happens depends on individual teachers, researchers, heads, politicians, pupils, parents, and more. It will take mischievous leaders, unafraid to question orthodoxies by producing good-quality evidence; and it will need to land with a community that – at the very least – doesn’t misunderstand evidence-based practice, or reject randomised trials out of hand.

If this all sounds like a lot of work, then it should do: it will take a long time. But the gains are huge, and not just in terms of better evidence, and better outcomes for pupils. Right now, there is a wave of enthusiasm for good-quality evidence, passing through all corners of government. This is the time to act. Teachers have the opportunity, I believe, to become an evidence-based profession, in just one generation: embedding research into everyday practice; making informed decisions independently; and fighting off the odd spectacle of governments telling teachers how to teach, because teachers can use the good-quality evidence that they have helped to create, to make their own informed judgements.

There is also a roadmap. While evidence-based medicine seems like an obvious idea today – and we would be horrified to hear of doctors using treatments without gathering and using evidence on which works best – in reality these battles were only won in very recent decades. Many eminent doctors fought viciously, as recently as the 1970s, against the very idea of evidence-based medicine, seeing it as a challenge to their expertise. The case for change was made by optimistic young practitioners like Archie Cochrane, who saw that good evidence on what works best was worth fighting for.

Now we recognise that being a good doctor, or teacher, or manager, isn’t about robotically following the numerical output of randomised trials; nor is it about ignoring the evidence, and following your hunches and personal experiences instead. We do best by using the right combination of skills to get the best job done.

A Rock of Crack

as Big as the Ritz

1

Guardian

, 21 February 2009

In a week where our dear

Daily Mail

ran with the headline

‘How Using

Facebook Could Raise your Risk

of Cancer’, I will exercise some self-control, and write about drugs instead.

‘Seven hundred British troops seized four Taliban narcotics factories containing £50m of drugs,’

said the

Guardian

on Wednesday. ‘Troops recovered more than 400kg of raw opium in one drug factory and nearly 800kg of heroin in another.’ That is good.

In the

Telegraph

, British forces had seized ‘£50 million of heroin and killed at least twenty Taliban fighters in a daring raid that dealt a significant blow to the insurgents in Afghanistan’. Everyone carried the good news. ‘John Hutton, Defence Secretary, said the seizure of £50m of narcotics would “starve the Taliban of funding preventing the proliferation of drugs and terror in the UK”.’

Well.

First up, almost every paper – the people we pay to précis facts for mass consumption – got both the quantities and the substances wrong. From the

MoD press release

(a romping read), three batches of opium were captured, but no heroin:

‘over 60kg of wet opium’, ‘over 400kg of raw opium’ and ‘the largest find of opium on the operation, nearly 800kg’.

So the army captured 1,260kg of opium. Opium is not heroin; it takes about 10kg of opium to make 1kg of heroin. They also found some

chemicals and vats

. The opium was enough to make roughly 130kg of heroin.

How much was this haul worth to the Taliban, and exactly how much of a blow will it strike? Heroin is not very valuable in itself, because opium is easy to grow, and you can turn it into heroin over the course of three simple steps using some school science-class chemicals in your kitchen (or a barn in rural Afghanistan). Heroin becomes expensive because it is illegal, so people must take risks to produce and distribute it, and as a result, they want money.

The ‘farm gate’ price of 1kg of opium in Afghanistan is $100 at best (we’ll use dollars, since the best figures are from the UN Drugs Control Programme

2008 world report

). So the 1,260kg of opium captured on this raid in Afghanistan is worth somewhere near $126,000 (not £50 million).

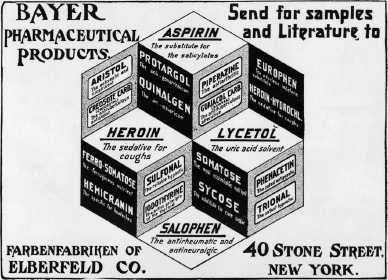

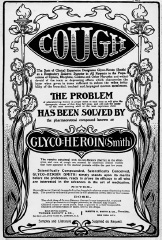

Even if it had been converted to heroin – it wasn’t – the money doesn’t get much better. The price for 1kg of heroin in Afghanistan is not much higher than the price for the 10kg of opium you need to make it. That’s because heroin was invented over a hundred years ago, and making it, as I said, is

cheap and easy

. We could be generous and say that heroin is worth $2,000 per kilo in Afghanistan: this would make the army’s (potential) 130kg of heroin worth about $250,000.

That’s still not £50 million. So where did this enormous number come from? Perhaps everyone was trying to calculate it by using the wholesale price in the UK, assuming that the Taliban ran the entire operation from ‘farm gate’ to ‘warehouse in Essex’. This is a stretch of our generosity, but we can still run the numbers: the

wholesale price of heroin in the UK has fallen dramatically

over the past two decades, from $54,000 per kilo in 1990 to $28,000 today. That would make our 130kg of (potential) heroin worth $3.6 million.

We’re still nowhere near £50 million. So: maybe the army thinks that every sweaty kid with missing teeth in King’s Cross selling £10 bags is actually a Taliban agent, passing profits on – in full, no cream off the top – to Taliban HQ, several thousand miles away in Aghanistan. Even then, UK heroin is $71 per gram at retail prices (down from $157 a gram in 1990), so the value of our 130kg is $9 million. We can be generous, and say our street heroin is only 30 per cent pure (it’s usually much better): in this case, finally, the haul is worth $30 million on the streets, or £20 million, at absolute best. To do this, we had to assume that every penny of the street-level UK retail price, at the smallest unit of sale, went straight to the Taliban, and that’s not £50 million.

But the most important thing about figures – once you’ve actually got them right – is to put them in their appropriate context. Even if we were generous, would 130kg less heroin make any difference to the UK market? No. We consume tons and tons of heroin every year, and the heroin from Afghanistan, in any case, is going all around the world, not just into the UK.

More importantly, would this seizure make much difference to the Taliban, whichever figure you use: $126,000, or $3.6 million, or $30 million, or £50 million? Again, that seems unlikely. There are 157,000 hectares (100 metres squared) of opium fields in Afghanistan, producing 7,700

tons

(not kilos) of opium, netting farmers throughout the country about $730 million, and that’s real money in their pocket, not made-up UK street prices on the diluted gram. The export value of opium, morphine and heroin at border prices in neighbouring countries for Afghan traffickers was worth $3.4 billion last year.

Just to remind you: John Hutton is the Defence Secretary, and he said that the seizure of £50 million of narcotics would ‘starve the Taliban of funding preventing the proliferation of drugs and terror in the UK’. That frightens me, because I trust the Defence Secretary to know what’s going on in a

war

,

and you didn’t even need to do the maths on his figure: this seizure was a tiny drop of theatre in a very, very big ocean.

Guardian

, 5 April 2008

There’s this vague idea – which has been going around for the past few centuries – that statistics is difficult. But in reality the maths is often the least of your problems: the tricky bit comes way before the number crunching, when you are deciding what to measure, how to measure it, and what those measurements mean.

The government’s new drugs strategy has been published, with outcomes that will be measured to see if it works or not. However you cut the cake, we should be clear: measuring drug-related death is difficult. You could look at death certificates to see what’s listed, but they’re often filled out by junior doctors, and

aren’t very informative

or reliable

. You also need to decide where to draw the causal cut-off. Does HIV count as a drug-related death, if you got it from a needle full of heroin? Or from sex work to fund the drugs?

How about if it kills you ten years after you become abstinent, or you die from chronic, grumbling hepatitis C from a needle? Or chronic, seeping, pus-ridden abscesses bulging deep in your groin from years of injecting your femoral veins?

And that’s before we get to crack-frenzy violence and drug driving. What if there was no toxicology done? What if there was, but they didn’t test for the drug the person took? What if the coroner finds some drugs in the blood, but doesn’t think they were related to the death? Are they consistent in making that call?

The new government drugs strategy solves this tricky problem by simply not measuring drug-related deaths as an outcome any more. It was a key indicator in our major strategy document ten years ago, but you won’t see death mentioned once in ‘

Drugs

: Protecting Families and Communities Action Plan 2008–2011.

You also won’t see death in ‘

Public Service Agreement Delivery

Agreement 25’, which includes measured outcomes such as the number of users in treatment and the rate of drug-related offending. A lot of drug users die. Death, even if you don’t like drug users, is important.

But beyond the disputes over how you collect these figures, there is the interpretation and analysis; and the greatest irony is that the government may have dropped drug-related deaths two weeks ago, simply because it misunderstood that the figures are actually looking quite good.

Overall, drug-related deaths show no great improvement over the years. But what if older people – over thirty-five, say, users from the great injecting epidemic of the 1980s – were dying at a greater rate, while young people, the target of great effort, are dying at a slower rate? That’s what a recent analysis from the biostatistics unit in Cambridge shows: they presented their findings just two weeks ago, in the same week, by odd coincidence, that the government announced its deathless drug strategy.