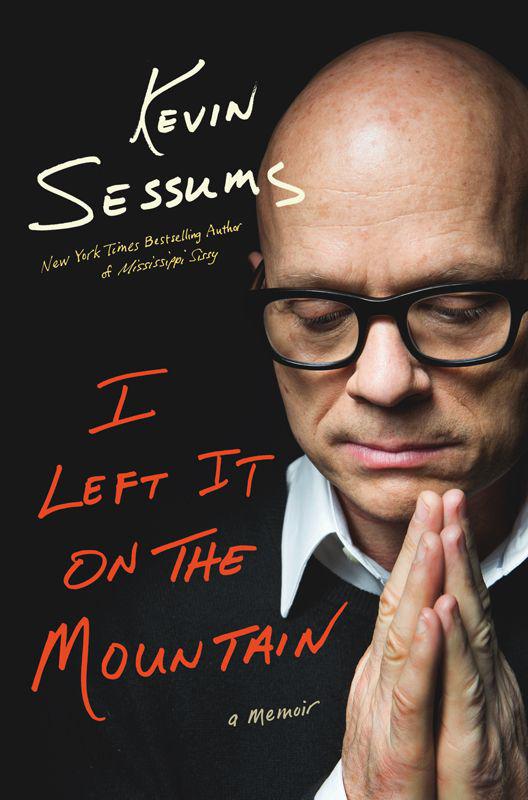

I Left It on the Mountain: A Memoir

Read I Left It on the Mountain: A Memoir Online

Authors: Kevin Sessums

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Journalist, #Nonfiction, #Personal Memoir, #Retail

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click

here

.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

for Perry Moore

Do you not see how necessary a world of pains and trouble is to school an intelligence and make it a soul?

—an excerpt from a letter dated May 3, 1819, and written to George and Georgiana Keats by poet John Keats

I’ve met some friends of yours. In fact, you seem to be known by everyone, and I have a whole new idea of your life. You were born and instantly flown to New York, where, like a Commissar of Culture, you proceeded down a long receiving line that included major and minor figures in the worlds of dance, drama, poetry, sculpture, architecture, and so on. The only thing you missed is alchemy.

—an excerpt from a letter dated July 22, 1983, and written to me by poet Howard Moss

Still in bed, I realized it was my fifty-third birthday. My next thought was about the adventure I was going to have in a month. As a kind of birthday present to myself I had decided, as suggested by my friend Perry Moore, to walk the Camino de Santiago de Compostela. The Camino is a spiritual pilgrimage of over five hundred miles across northern Spain that pilgrims have walked for over two thousand years. Maybe that was why I was having so much trouble getting out of bed that birthday morning—not that I was another year older, but that my body had already begun to rebel at having to walk those five hundred miles of a trek my depleted spirit was demanding of it.

I cracked open an eye: another hotel room. Down the hill outside my window, Los Angeles, like me, lolled and continued to wake. I have awakened in many such overly conceptualized hotel rooms in Los Angeles since becoming known as a writer uninhibited by fame. I cracked open my other eye in that one six years ago and focused on it all. The low-slung sofa a sloe-eyed decorator, no doubt, deemed, “Divine!” before demanding an assistant buy it in bulk at the Pacific Design Center out there down that same hill outside my window so he, the sloe-eyed one, could then speed off to Melrose to make a tattoo appointment, his bicep finally big enough to have Emily Dickinson’s entire two lines “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers / that perches in the soul” inked across it. Next to the sofa was a rather tatty red repro Saarinen chair. But the thing I recall the most from that immobile morning I turned fifty-three is my featherless solitude. They were—the sofa, the Saarinen, the solitude—the same somehow: each carefully chosen, precisely placed, all elements of an acquired aesthetic.

Many of my assignments over the years have taken me to LA to interview the phalanx of movie stars over whom I have mostly fawned. “The Impertinent Fawner” could have been printed on my business cards if I had ever thought myself in need of any. I had—I have—chosen a life free of business cards. That alone, I tell myself still, is accomplishment enough.

Or has it been? Is it?

Is it enough for a man to interview Madonna?

Is it man enough?

She was the first person about whom I wrote a cover story for

Vanity Fair

during my fourteen years there as a contributor after my stint as executive editor at Andy Warhol’s

Interview

. This was, however, the once-upon-a-time Madonna, the one during

Dick Tracy

and Warren Beatty, before Malawi and Lourdes and alleged face-lifts, the one who has found a way, unlike me so far, to inhabit her fifties. Back when I first met her she had, through her first surge of real wealth, an aesthetic that could also be described as an acquired one. Her pride at her good taste outweighed her need for privacy at that point and she invited me to her home.

It was January 1990. Time Inc. and Warner Brothers were about to merge. The Leaning Tower of Pisa needed repair and was suddenly closed to visitors. A few days before, the Dow Jones reached a record 2,800 points. Jim Palmer and Joe Morgan were to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame that month and Panama’s Manuel Noriega was to surrender to American forces. Moscow was getting its first McDonald’s.

The Simpsons

was ready to premiere on the fledgling Fox Network. And I was sitting in the back of a black sedan being driven high into the hills overlooking all of Los Angeles, a kind of city-state replete with valet parking, huevos rancheros, and replication. I stared out my window. On one side, down below, was the gnarl of Sunset. On the other, looming even larger, was the Valley in a city that states: This is what a valley is.

The sedan pulled into Madonna’s drive. I waited a bit before getting out, because I was early for the interview. It is a trait of mine—arriving early—ingrained in me by my grandfather, who made sure, back in my Mississippi childhood, that ours was the first car each Sunday morning in the parking lot of Trinity Methodist Church. He would then make all of us, my grandmother and brother and sister and me, wait until the second family drove up for the worship service before we could get out. Then on his cue—an exaggerated groan as he opened his door and unfolded his body—we all climbed from the car.

Madonna’s house up in those hills that day was as far from Trinity Methodist’s parking lot as I had ever traveled. With an exaggerated groan I unfolded my own body and, climbing from the car, climbed from the life that had brought me to such a place.

* * *

I rang Madonna’s bell and readied myself for one of her assistants to answer it. Wrong. “Ready or not, here I come!” could, since her own childhood, have been her mantra, the mantra of a woman who has never hidden from but always sought herself. Why had it surprised me—she could not disguise her satisfied grin when I gasped a little at the sudden sight of her—when it was she who swung open the door to greet me?

She wore no makeup at all that day except for lipstick that had been applied to the now-reddest lips allowed in town. On her tiny, exquisitely toned legs she was wearing black fishnet stockings beneath black cutoff jeans. She had not buttoned the top three buttons on a studded black denim shirt. A black leather cap was cocked atop her head. Black pumps were on her feet. Even the straggly strands of dirty hair streaming from under that cap were surprisingly dark, for she had planned, slyly so, to end our time together that day in her kitchen as I watched her eat a big bag of barbecue potato chips and feign bemusement at the trashy tabloids she purposefully had waiting for her perusal, all the while getting her hair washed in the kitchen sink, then dyed yet again back to the blond color that was her showbiz shade.

The house, like her, was surprisingly small, startlingly white, all modern angles and hard edges. Everywhere there was an exquisite incongruity. Outside, a black Mercedes 560SL was parked next to a coral-colored ’57 Thunderbird; inside, twentieth-century art hung above eighteenth-century furniture. Candles, embossed with Catholic saints, dotted the house’s sophisticated rooms. On a kitchen counter, audiotapes of Joseph Campbell’s

The Power of Myth

lay stacked beside tapes by Public Enemy.

Atop her work desk was a beautiful portrait of her mother, who died of cancer when Madonna was six. “My memories of her drift in and out,” she admitted to me. “When I turned thirty, which was the age my mother was when she died, I just flipped because I kept thinking I’m now outliving my mother.”

I didn’t gasp this time, but I did noticeably blanch. My mother had died at the age of thirty-three from cancer when I was eight and I, having already outlived her by several months, was about to turn thirty-four in a matter of weeks. The fact that I had also by then outlived my father, who had just turned thirty-two when he was killed in a car crash before my mother’s illness, didn’t lessen the odd panic I had been experiencing. It only served as the panic’s foundation. Fed it. It was a heady feeling. Addictive? Perhaps. I only knew I was ironically growing to depend on such panic to feel alive.

I told Madonna of this shared panic of ours when she asked if I was all right. I had planned to match her brashness that day but had not anticipated just how brash we would instantly be with each other. It threw me. Where do I take the conversation from here? I was thinking, but there was no need to worry. She remained firmly in control.

“I thought something horrible was going to happen to me when I turned thirty,” she said, reaching down and straightening the frame that contained her mother’s image. Had the woman in that picture known already that she had cancer? Had she sensed something awful was about to happen? I stared into the eyes of Madonna’s mother, eyes that a long-ago camera lens had caught in an unguarded moment. I saw the anger that had embedded itself there, the sorrow, peering back at me from beneath my own reflection.

“I kept thinking, like, this is it, my time is up,” said Madonna, cutting her eyes defiantly my way after they had caught mine there in the glass atop her mother’s face. Madonna’s defiance somehow gladdened me. It was, in essence, her allure. She continued to straighten her desk. “It was a tough year last year. I was going through so many things … and my divorce…,” she said, mentioning Sean Penn without mentioning his name.

An ornately gold-framed Langlois, originally painted for Versailles, was as large as the entire ceiling in the house’s main room, and that is exactly where Madonna had hung it, Hermes’s exposed loins dangling over our heads as we headed that way. Boxer Joe Louis, photographed by Irving Penn, pouted in a corner across from May Ray’s nude of Kiki de Montparnasse. Above the fireplace was a 1932 Léger painting,

Composition

. Across from it was a self-portrait by Frida Kahlo.

Earlier, in the entrance foyer, I had walked by another Kahlo. I stopped following Madonna about the house long enough to walk back toward it all by myself. She now followed me. I asked her the painting’s name. “

My Birth,

” she told me, coming to stand close beside me and gaze also at the image. It depicted Kahlo’s mother in bed with the sheets folded back over her head. All that could be seen of the mother were her opened bloody legs, the head of the adult Kahlo emerging from between them.

Madonna touched my arm.

“If somebody doesn’t like this painting,” she said, “then I know they can’t be my friend.”

* * *

I did like the painting—it haunts me still—but I did not become her friend. We became, as one does so often where I reside just outside the frame of fame, heightened acquaintances. It’s the kind of public relationship that can so easily flow from the intimacy that a good interview engenders when it veers into a conversation performed as a private one. Madonna and I, veering, talked a lot that day about abandonment because of the deaths of our mothers from cancer when we were children. “I don’t know if going to a shrink cures the loneliness caused by such abandonment,” she’d confided, “but it sure helps you understand it.”