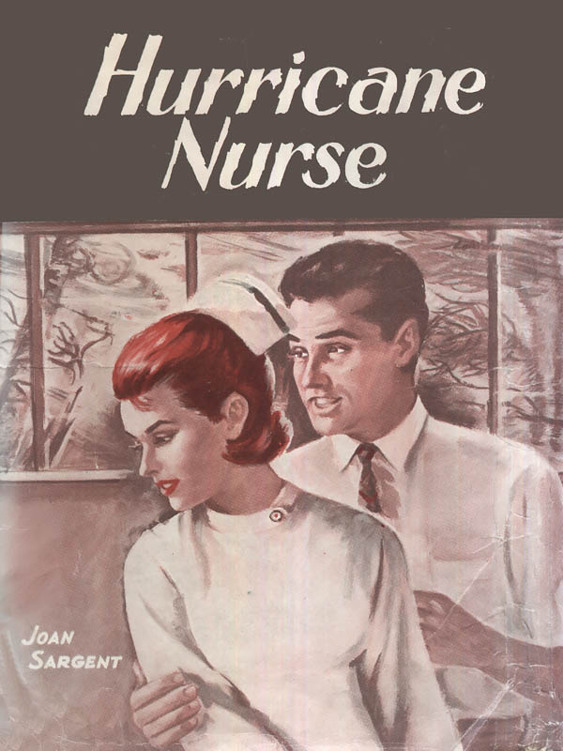

Hurricane Nurse

by Joan Sargent

Scanned and Proofed by Highroller and RyokoWerx

who deeply apologize for the hell we're about to inflict on you.

Although Donna Ledbury had been a school nurse only six weeks, she was experienced enough to recognize that today was going to be one of those days. Ordinarily by nine in the morning, she had checked supplies, made out the run-of-the-mill parts of her daily report and gone across to the gymnasium, where she was testing sight, hearing, weight, teeth, and general health of pupils, in preparation for the more expert attention of the doctor who would come later. Today she had soothed two first-graders who wanted their mothers, put ice on a black eye resulting from a fight before school, looked at a suspicious rash on one of the sixth-grade teachers, and given sympathy and an aspirin to a third-grade teacher.

Her head ached a little and she realized that she was going to have to watch herself if she were to remain patient and soft-spoken to the pupils.

Her disposition was more like sandpaper, this morning, than like sugar. She gathered up her eye chart, the man-sized watch with which she tested hearing, her pocketbook, and turned toward the gym.

As if he had been watching for her to emerge from her office, Henry Fincher, the principal, popped from his office across the hall and smiled at her. "Did you hear the weather report before you left your apartment this morning?" he asked.

She shook her head. "I'm a night person, I guess. Anyway, I'm dead to the world until my alarm goes off, and then I have to gulp my coffee and brush my hair at the same time in order to catch the bus and get here by eight. Hurricane Camilla still heading our way?"

She was always a little surprised when she looked at the young principal of Flamingo Elementary School. He didn't look at all the way she had thought men teachers were supposed to look. The boys at Teachers' College where she had taken two courses in school nursing—she had been studying nursing at the medical college across the street—hadn't led her to expect anything like Hank Fincher. She was a tall girl herself, but she had to look sharply up to meet his eyes. His shoulders were broad, his hips narrow, and his features would be hard to improve upon. By almost anyone's standards, Henry Fincher was a handsome man—and a quite masculine one.

Just now, the tanned face below the blond hair looked anxious. "The weather report early this morning said that Camilla had speeded up. And she's headed straight toward Miami. She's expected to strike about six tomorrow morning."

Donna shivered a little and made a deprecating face at her own lack of consistency. "I don't know whether I'm more excited or more scared," she said. "I've never seen a hurricane."

He didn't look amused. "Once you've seen a really bad one, you'll be more scared. Hurricanes do so much property damage and nearly always there are casualties." He did smile then. "I'm particularly angry with Camilla. I intended to ask you to have dinner with me tomorrow night and afterwards go to the play at Studio M. And now I can't even give you the privilege of saying no."

"You—you mean it won't be over by tomorrow night?" she asked wonderingly.

"The hurricane will last three days if it's as bad as they expect," he told her. "The school will be turned into an emergency center and I'll have to be here until the last refugee is gone."

She frowned a little trying to understand the seriousness of it all. She had seen stores being boarded up yesterday after school, had realized that the grocery store where she had stopped to do a little shopping (it was her week to cook at the apartment) had more shoppers than usual. Most of them had jugs of kerosene oil and great bags of groceries, and all of them talked louder than was customary. But she had stayed late at school for a P.T.A. meeting and her mind had been on getting dinner ready by seven.

The girls at the apartment weren't paying a great deal of respect to the elements, either. "Oh, they get all wound up like this every year," Nell Simmons had said impatiently. "Usually more than once. I've been in Miami three years and nothing's happened so far. I'm bored with it all."

"We'll fill the tub with water and cook up everything in the refrigerator that might spoil tomorrow, if it looks like it's going to be really bad," Kathy Craig, who had lived in South Florida all her life, said. "We've got a lamp and some candles in case the electricity goes off. The winds could do a complete turn-about between now and the time it will take the storm to get here. I wouldn't get excited yet."

Evelyn Bates, who was always more interested in parties than the other three, spoke lazily from where she lay on the couch. "The boys can bring in groceries and drinks, and we'll have a bang-up time."

"Groceries and drinks?" Donna had echoed in amazement.

"Even if you haven't been here but a month," Evelyn laughed at her, "surely you have heard of hurricane parties? They're one of the nicest features of our fair city."

"You let me tell our baby about hurricane parties, Evelyn," Nell ordered. "Your tales are too lurid for her young ears. And too lurid for the sort of party we'll be having. Friends gather, Donna. They play cards and listen to a transistor radio for the next report."

"And eat," Kathy added, taking a bite of the sandwich she held in her hand.

Donna had taken her groceries into the kitchen and begun to prepare dinner. There had been more talk about the storm, but most of it had been the sort of foolishness her apartment mates and their dates carried on all the time, and she thought little of it. Now, she was forced by Hank's worried face to take it all seriously. Her face grew a little paler. The dimples that usually danced on her cheeks disappeared. Even her red curls seemed to darken.

Hank forced a smile. "Forget it, Donna. There's no need to cross bridges yet a while, even if the barometer is going down at a rate; the storm could pass north of here, or south, and we'd only get a hard rain, which we need."

She rubbed her forehead at the temples and smiled, too. "A nurse isn't supposed to be a coward, is she?"

He spoke sympathetically. "Headache?"

She rubbed her temples again. "A little. I've taken an aspirin. It'll go away soon."

"It's the low barometer. The pressure does strange things to people. We always expect youngsters to give us more trouble on days like this than at any other time, and they don't disappoint us."

She really smiled now. "Is that why I had to mop up after a fight this morning? And why the little ones wanted to go home to mother though they've been acclimated to school nearly a month now, even the worst crybabies?"

He gave a pleasant, deep chuckle. "That's why."

She clutched her eye chart and her watch closer to her breast and laughed. "That's why I'm late starting my tests. That, and talking to the fascinating principal at Flamingo Elementary. I've got to run. But I'll take a—hurricane check on that dinner and show if you'll let me."

"It's a date," he said, pleasure in his voice.

She gave him a small salute and turned toward the door leading to the gym, a tall, efficient-looking girl with a proudly held red head, who managed to look like an excitingly feminine creature in the starched blue and white uniform which all the school nurses wore.

Her chest felt heavy, as if she had been breathing hard for a long time. She drew in a deep breath and let it out again, but it did nothing to relieve her air hunger. She noticed that the palms that decorated the school grounds for once weren't whispering like rainfall, and when she looked, there wasn't a leaf stirring anywhere. Usually through all the town, no matter how hot the day, you could count on a brisk breeze out-of-doors. Nor was the vaunted South Florida sun shining. The sky was not so much clouded as turned the color of unpolished pewter.

The gym smelled of the rubber soles of tennis shoes and gym suits that should have gone to the laundry after the class before the last. She began to line up the seventeen little girls with the help of their teacher, who was elderly and professionally patient. Already, her long hair was beginning to slip from its knot. Donna smiled inside, thinking that Miss Graves looked rather like she herself felt. She would even be willing to bet that Miss Graves's head ached.

Miss Graves set about measuring heights and weights, picking a bright-eyed sixth-grader to mark them down on a foolscap-length piece of paper. Donna busied herself with the eye chart and the watch.

The morning dragged along. Donna was working on the third group of girls when the loudspeaker outside the gym set up the squawk that meant the principal would soon speak to the entire school. Miss Graves had been replaced by Mrs. Tutan, who was nervous about the storm and didn't care who knew it. She grabbed Donna's arm, her eyes big with alarm. "Oh, I hope he hasn't waited too long and we can get all the children home. If we have to stay here with them, my husband will be wild."

Hank's voice, calm and precise, came over the speaker. "There is no reason for anyone to be frightened. Because we expect to use Flamingo Elementary as a storm shelter and must get ready, we are dismissing school in fifteen minutes. Buses are waiting for pupils who ride them. Parents have been notified about the early closing by radio and television. Pupils are asked to take all their books home. Teachers will empty desk drawers and take all records with them. Books should be locked in supply cupboards. That is all. Thank you."

Everyone in the gym began excited remarks, more to express their own thoughts than to communicate with anyone else. A girl was sent out on the grounds to relay the message to the men coaches, and the rest of the girls were herded into dressing rooms to change their uniforms for their everyday school dresses.

Mrs. Tutan clutched Donna's arm with both hands and muttered, "I knew it. The hurricane will be here before we can get away from the schoolhouse."

Donna shooed their charges into line, advised, "You'll have to get back to your home room immediately," and soothed Mrs. Tutan in a whisper, "I feel sure Mr. Fincher meant what he said. He's not deceiving us."

Mrs. Tutan gave her a dire look and warned, "Of course

you

think that. You're in love with him," then followed the girls outside into what was beginning to be a drizzle of rain.

Donna gathered up her paraphernalia and locked the door of the room behind her. All her actions were automatic; her mind was weighing what Mrs. Tutan had just said to her. Others of the teachers had teased her ever since her first date with Hank. Dolly Weir, a teacher with whom Donna frequently had lunch, called her "principal's pet," and went out of her way to suggest that Donna ask Mr. Fincher for something which, according to her, the teachers wanted. These alleged requests were usually as farfetched as a holiday for the birthday of Genio (the Ox) Alcotti's birthday, but Donna got the message that the teachers realized Mr. Fincher was at least interested in the new school nurse.

She had joined in the joking, laughed with the rest. She, too, knew that Hank Fincher was showing signs of being in love with her, and sometimes, on the verge of sleep at night, she had weighed her own feeling for him. She always dropped off to sleep before she came to any conclusion. She liked Hank. She always had fun when they went out together. But was that love?

She knew no more today than on other times when she had considered the matter.

The drizzle had turned to rain and there was a little wind now, enough to set the palms to rattling. She ran across the narrow bit of campus to the school building and went down the long hallway to where her office flanked the main entrance. She went in and began to empty her desk according to orders. It was a funny thing to do when all the desks could be locked, and who would want schoolbooks and reports, anyway?

But she had learned early in her nurse's training to obey orders. She finished her daily report, placed her report books on her desk beside her purse and began to lock the cabinets. Outside, she could hear the buses pulling away, the voices of mothers urging their little ones into cars, the shrill voices of children arguing, asking questions, reporting what had gone on at school. Teachers were beginning to chatter like starlings in front of the time clock. She closed her door and locked it.

She would have gone in to punch the clock herself, but a small weeping boy, wiping eyes and nose on his sleeve, caught her attention and she went to him, instead, dropping to a squatting position so that her face was level with his. "Something the matter?" she asked, quite as if she were his age.

He nodded, beginning to wail aloud now that he had found a listening ear, and to hiccough out his words, so that she could understand nothing of what he was saying.

She produced a tissue from her purse and offered it. "Mop up, fellow," she ordered. "And you'll have to speak clearly enough for me to understand you before I can help."

"M-my m-mother," he stammered. "She didn't come in the car to get me. The storm is going to come and sail me through the air and bash me against a building and—"Misery swamped further words.