Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives (30 page)

Read Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives Online

Authors: Carolyn Steel

Having made the case for housework to be held in higher regard, Beecher came to the crux of the matter: how it was to be carried out. The immediate problem that struck her was one of efficiency. Now that housewives were having to cook for themselves, their labour-intensive kitchens were hopelessly inadequate. Beecher’s solution was simple: to restore the kitchen to the centre of the home. That way, a housewife could do everything she needed, while keeping an eye on

her children and her other housework. Beecher may have restored the ancient marriage of hearth and home, but her view of the relationship was far from romantic. Her ideal house plans had more in common with Jeremy Bentham’s

Panopticon

(a circular ideal prison plan that allowed all the cells to be surveyed from a single central guardroom) than with John Ruskin’s temple.

46

This was no misty-eyed vision of the sacred housewife; women were simply placed at the centre of the domain they were expected to control. Cooking, along with other womanly duties, was a job that had to be done. As for the kitchen itself, it needed to be radically simplified: in later writings, Beecher compared it to a ship’s galley.

Beecher’s many followers included Ellen Richards, whose degree in chemistry from MIT was the first in science ever awarded to a woman. Whereas Beecher had sought to give housewives social dignity, Richards wanted to turn them into scientists like her; ones with urgent duties to perform at that. In 1861, the ‘germ theory’ posited by John Snow had received clinical proof from the French chemist Louis Pasteur, whose laboratory experiments confirmed that micro-organisms in nutrient broth were the result of external contamination.

47

Richards was among the first to understand the implications of these findings: they made kitchens far more dangerous places than anyone had realised. With the connivance of her long-suffering husband, she turned her home into an experimental laboratory, investigating every possible application of science to cookery and housework. Meanwhile, she urged for chemistry to be taught to women so that they could fight food adulteration and contamination for themselves. In 1876, Richards finally got permission to set up a Women’s Laboratory at MIT. Here she instructed women in the ‘advanced study of chemical analysis, mineralogy, and chemistry related to vegetable and animal physiology and to the industrial arts’, the basis of the new discipline she was to call ‘domestic science’. Richards was a visionary, but sadly her dream of a new generation of chemically aware housewives inspired by ‘the zest of intelligent experiment’ never came to pass.

48

Instead, increasing awareness of ‘germ theory’ caused widespread panic about dirt in all its forms. The mood at the turn of the century was summed up by Mrs H. M. Plunkett, author of

Women, Plumbers and Doctors, or Household Sanitation

,

in 1897. A housewife’s failure to prevent disease, she said, was ‘akin to murder’; her neglect of proper cleaning ‘tantamount to child abuse’.

49

It would rest with a pupil of Richards, Christine Frederick, to come up with some practical advice that housewives could actually follow. Through her husband’s work as a factory inspector, Frederick had become aware of a revolution then taking place in factories: the streamlining of production methods that would become known as ‘Taylorism’. In 1899, a mechanical engineer named Frederick Taylor had been asked to analyse the working practices of a group of pig-iron workers to see if he could increase their productivity. Taylor performed the world’s first time-and-motion study on the workers, plotting their various tasks and the sequence in which they were carried out. He concluded that many of the workers’ movements were unnecessary, and proposed a new ‘production line’ approach to streamline their actions and maximise efficiency. The principles of Taylorism are widely familiar today, but when Christine Frederick first heard about them, they were revelatory. She came up with the idea of applying them to kitchens; for, as she put it with unarguable logic, ‘Why walk eight feet to a kitchen table and eight feet back again for the bread-knife which is always needed near the bread box kept on the cabinet across the room?’ In her 1915 book

Efficient Housekeeping, or Household Engineering

, Frederick contrasted two different kitchen layouts, one ‘efficiently grouped’ and the other ‘badly grouped’, to explain how each responded to the cooking process: ‘This principle of arranging and grouping equipment to meet the actual order of work is the basis of kitchen efficiency. In other words, we cannot leave the placing of the sink, stove, doors and cupboards entirely to the architect.’

50

The result of her analysis was the ‘labor-saving kitchen’: the first kitchen designed entirely around the ergonomics of cooking. It featured cabinets with pull-out worktops, built-in hoppers for flour and sugar, and ‘workshop-style’ wall-mounted storage racks for utensils. The kitchen, said Frederick, should be full of light and air, avoiding the ‘ugly green or hideous blue colourings’ of former times. Work surfaces should be ‘covered with non-absorbent, easily cleaned materials’ to make them germ-free and easy to maintain.

51

As for the actual work to be done, housewives were to adopt an ‘efficiency attitude’, making lists of tasks to be achieved each day and ticking them off as they went along – even timing themselves to monitor their own performance. There was no room for slackers in Frederick’s engineered household. In a tone that makes even the late Fanny Cradock seem conciliatory, she continued: ‘There is no excuse for “Oh, I forgot to order more sugar”, for making four trips upstairs which could have been taken in one, or for finding that there isn’t another egg in the house.’

52

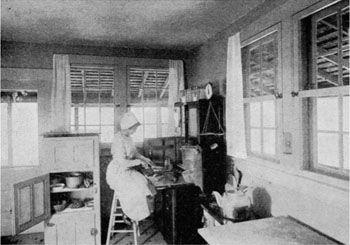

The ideal housewife at work. Illustration from

Household Engineering

.

Frederick believed that her methods were ‘a route from drudgery to efficiency and personal happiness’, and strangely, her readers seemed to agree. More textbook than cookbook,

Household Engineering

ended each chapter with a series of questions for readers to answer, like an exam. Yet far from having nightmares about being back at school, women wrote to her in their thousands, begging for more information about her methods. Whether they managed to live up to her exemplary standards was another matter.

Home-maker, intellectual, scientist, engineer: American housewives had been through a few paradigm shifts by the start of the First World War – as had their kitchens, from hearth to galley, laboratory and factory. By the time European architects faced the task of postwar reconstruction, the ‘engineered’ kitchen was a ready-made prototype that would fit right into their new way of thinking. The mood in Europe after the war was evangelical: designers, philosophers and politicians alike felt the need to build a new world that would liberate mankind not just from the horrors of war, but from the social iniquities that preceded it. For that, they needed not just new sorts of buildings, but a whole new approach to living in them.

The role of women in creating this new world was recognised by one country in particular. Germany, like America, had a long-established women’s movement, whose members had since the 1880s been addressing issues of household efficiency, the teaching of domestic economy in schools and so on. The value of their work was recognised by architects such as Bruno Taut, who in 1924 summed up his view of the ideal architect–client relationship with the motto ‘

Der Architekt denkt, die Hausfrau lenkt

’ (the architect thinks, the housewife guides).

53

When Christine Frederick’s book was translated into German after the war, it found an eager readership, among them the Austrian-born female architect Grete Lihotzky, creator of one of the most influential designs of the twentieth century, the ‘Frankfurt kitchen’. Partly inspired by a railway carriage galley, the Frankfurt kitchen was essentially a scaled-down version of its American predecessor. Designed to be cheap and compact, it had a number of space-saving devices, such as a fold-down ironing board and a series of pull-out metal hoppers (à la Frederick) for basic ingredients such as rice, sugar and flour. It was the first kitchen ever to be mass-produced – more than 10,000 were installed in Frankfurt’s social housing programme during the 1920s – and it was the prototype for the modern fitted kitchen in ubiquitous use today.

Despite its ingenious design and commercial success, the Frankfurt kitchen was not universally loved. Designed around the body movements

of a housewife performing her daily tasks, it effectively cut women off from the rest of the home – and from their own families. The kitchen was found to be inflexible: too small for two people to cook in at once; impossible for children to play in (the pull-out hoppers were temptingly within toddler range); and certainly too small to eat in. All this was deliberate on the part of Lihotzky: by the 1920s, the idea of cooking and eating in the same space was considered unhygienic. For Lihotzky, cooking was a chore, and must be separated from its object, the meal. As she herself put it, ‘What is life today actually made of? Firstly, it consists of

work

, secondly of

relaxing

,

company

,

pleasure

.’

54

Liked or not, the Frankfurt kitchen’s success ensured that the no-nonsense – and no-pleasure – approach to cooking pioneered by American feminists would have a lasting impact in the West. Once again, cooking was banished to the invisible parts of the house; only this time, the mistress of the house was banished with it. Far from releasing housewives from drudgery as intended, the Frankfurt kitchen – and the millions of galley kitchens that followed in its wake – would ensure that cooking would remain the isolated, thankless task that polite society had always believed it to be.

The Frankfurt kitchen exposed a fatal flaw within early modernist thinking that has plagued approaches to architecture ever since. With the best of intentions – the building of a better society – modernism tried to create a world so perfect it would liberate men and women from their own imperfections. Household engineering became social engineering: the creation of rational buildings that demanded rational people to live in them. Of course the whole thing was an illusion – a sleight of hand that owed most of its power to the undeniable beauty of much modernist design. Yet the image was powerful enough to stick. Even today, the idea that society’s salvation might come through design alone seems, at least to some, perfectly plausible.

The man chiefly responsible for promulgating this vision of a brave new world was the Swiss-born architect Le Corbusier. For him, the cluttered interiors of

fin de siècle

Europe reflected the ‘crushing bourgeois values’ of ‘an intolerable period which could not last’.

55

Nothing short of a complete physical and moral purge was required, and in a series of caustic essays, including his groundbreaking manifesto

of 1923,

Vers une Architecture

, Le Corbusier showed his readers the way. ‘Demand bare walls in your bedroom, your living room and your dining room,’ he commanded. ‘Once you have put ripolin [whitewash] on your walls you will be

master of yourself

. And you will want to be precise, to be accurate, to think clearly.’

56

As the architect Mark Wigley has observed, Le Corbusier used the colour white as a sort of architectural hygiene, much as men in the eighteenth century might have put on a white shirt instead of washing.

57

Le Corbusier believed that by living in a pure environment, modern man would be purged of his imperfections both physically and morally: ‘His home is clean. There are no more dark, dirty corners.

Everything is shown as it is

. There comes inner cleanness …’

58

The stripped, white building was to become the leitmotif of modernism, an image fixed by the Stuttgart Weissenhofsiedlung of 1927, an international exhibition of model housing designed by a who’s who of twentieth-century architects, including Peter Behrens, Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Hans Scharoun and Bruno Taut. The Weissenhof housing – clean, pure and white to a fault – had enormous impact, as did the series of modernist tomes that followed in its wake, such as F.R.S. Yorke’s seminal survey of 1934,

The Modern House

. But as Yorke’s book illustrates, the socialist intentions of early modernism hid an underlying paradox. ‘We do not need large houses, for we have neither large families to fill them nor domestics to look after them,’ he wrote, yet the iconic villas in his book suggested otherwise.

59

All but a few had separate kitchens linked to substantial servants’ quarters.

60

Even Le Corbusier’s supposedly proletarian Maison Citrohan, the prototypical ‘machine for living in’, had a separate kitchen and service entrance with a maid’s room off it.

61

Despite Le Corbusier’s pronouncement that everything was ‘shown as it is’, not quite everything was. Modernism glossed over the problem of cooking by putting all its mess behind a wall. As Reyner Banham observed in his book

Theory and Design in the First Machine Age

, the defining works of the modern movement focused on the pure image of the buildings, rather than on the biological needs of their inhabitants.

62