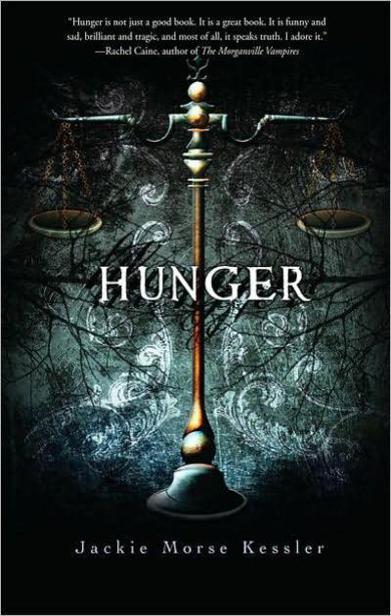

Hunger

Authors: Jackie Morse Kessler

Jackie Morse Kessler

G

RAPHIA

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Boston New York 2010

IF YOU HAVE EVER LOOKED IN THE MIRROR

AND HATED WHAT YOU SAW, THIS BOOK

IS FOR YOU.

Copyright © 2010 by Jackie Morse Kessler

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Graphia,

an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

For information about permission to

reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003

Graphia and the Graphia logo are registered trademarks of

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

The text of this book is set in Adobe Garamond.

Book design by Susanna Vagt.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kessler, Jackie Morse.

Hunger / Jackie Morse Kessler.

p. cm.

Summary: Seventeen-year-old Lisabeth has anorexia, and even turning into

Famine—one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse—cannot keep her

from feeling fat and worthless.

ISBN 978-0-547-34124-8 (pbk. original : alk. paper) [1. Anorexia

nervosa--Fiction. 2. Eating disorders—Fiction. 3. Emotional

problems—Fiction. 4. Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse—Fiction.]

I. Title.

PZ7.K4835Hu 2010

[Fic]—dc22

2009050009

Manufactured in the United States of America

DOM 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

4500251676

Lisabeth Lewis didn't mean to become Famine. She had a love affair with food, and she'd never liked horses (never mind the time she asked for a pony when she was eight; that was just a girl thing). If she'd been asked which Horseman of the Apocalypse she would most likely be, she would have probably replied, "War." And if you'd heard her and her boyfriend, James, fighting, you would have agreed. Lisa wasn't a Famine person, despite the eating disorder.

And yet there she was, Lisabeth Lewis, seventeen and no longer thinking about killing herself, holding the Scales of office. Famine, apparently, had scales—an old-fashioned balancing device made of brass or bronze or some other metal. What she was supposed to do with the Scales, she had no idea. Then again, the whole "Thou art the Black Rider; go thee out unto the world" thing hadn't really sunk in yet.

Alone in her bedroom, Lisa sat on her canopied bed with its overflowing pink and white ruffles, and she stared at the metal balance, wondering what, exactly, she'd promised the pale man in the messenger's uniform. Or had it been a robe? Frowning, she tried to picture the delivery man who'd just left—but the more she grasped for it, the more slippery his image became until Lisa was left with the impression of a person painted in careless watercolors.

Maybe the Lexapro was messing with her.

Yeah

, she thought, putting the Scales on her nightstand, next to a half-empty glass of water (which rested on a coaster) and a pile of white pills (which did not),

I'm high as a freaking kite.

And you're fat

, lamented the negative voice, the Thin voice, Lisa's best friend and worst critic, the one that whispered to her in her sleep and haunted her when she was awake.

High and fat

, Lisa amended.

But at least I'm not depressed.

Or dead; the delivery man had rung the doorbell before Lisa could swallow more than three of her mother's antidepressants. Bundled in her white terry cloth bathrobe over her baggy flannel pajamas, Lisa had answered the door and accepted the parcel.

"For thee," the pale man had said. "Thou art Famine."

And once Lisa had opened the oddly shaped package, all thoughts of suicide had drifted away. Thanks to the pills, that was sort of the way she was feeling now, as if she were drifting—drifting slowly like a cloud in the summertime sky, a cloud shaped like a set of old-fashioned scales...

The pills.

Pulling her gaze from the Scales, Lisa scooped the pills into her nightstand drawer. She wiped away the stray trails of powder, brushed off her hands, and gently closed the drawer. It wasn't as if she had to worry whether her mom would notice that her stash of bliss had been depleted; Mrs. Simon Lewis was off at some charity event or another, accepting some award or another. Lisa just didn't want to leave a mess. Even if she

had

overdosed, as she had originally planned, she would have died neatly in her own bed. Lisa tried her best to be considerate.

She frowned at the Scales. Dappled in moonlight there on her nightstand, they gleamed enticingly. Lisa couldn't decide if they looked ominous or merely cheesy.

Cheddar cheese, one ounce

, the Thin voice announced.

One hundred fourteen point three calories. Nine point four grams of fat. Forty minutes on the exercise bike.

And behind that, the pale man's words burned in Lisa's mind: "

Thou art Famine.

"

Uh-huh. Right.

Famine having a set of old-fashioned scales, Lisa decided, was stupid. The only scales that mattered were the digital sort, the ones that also displayed your body mass index.

Lisa yawned. Her head was fuzzy, and everything seemed pleasantly blurred, soft around the edges. It was peaceful. She thought about closing her window shade, but she decided she liked the moonlight shining on the Scales—sort of a celestial spotlight.

You're loopy

, she scolded herself.

Hallucinating. Get some sleep, Lisa.

She settled down on her bed, pulling the princess pink covers around her to fend off the chill. Lately, she was always cold—and hungry. Although she enjoyed the feeling of hunger, she hated it when her body shivered. Whenever she forced her body to stop shivering, it made her teeth chatter. And when she forced her teeth to clamp shut, her body shivered. It was a physical conspiracy.

Lisa gripped the blankets tightly and started thinking about the homemade cookies she'd make for Tammy tomorrow. As she imagined the smell of chocolate chips, she calmed down. Baking was soothing. And Tammy was a fiend for Lisa's baking. James was, too, but he always acted hurt when she wouldn't taste any of the sweets she made for him.

Snuggled like a baby, Lisa stared at the object on her nightstand. Backlit by the moon, the Scales seemed to wink at her.

"

Thou art Famine.

"

She let out a bemused laugh. Famine. Really. She would have made a much better War.

Smiling, Lisa closed her eyes.

***

The black horse was in the garden directly beneath Lisa's window, invisible, waiting for its mistress to climb atop its back and go places she had never imagined—the smoke-filled dance clubs of Lagos, dripping with wealth and hedonism; the opulent world of Monte Carlo, oozing with indulgence; the streets of New Orleans, filled with its dizzying smells and succulent foods. In particular, the horse had a fondness for Nola's sweet pralines.

Perhaps they would go to Louisiana first—perhaps even tonight.

The black horse snorted and pawed the grass, chiding itself in the way that horses do. So what that it wished to move, to fly, to soar across the world and feast? It was a good steed; it would wait forever, if needed, until its mistress was ready to ride.

It wasn't the horse's fault that it was impatient; the rhododendrons in the garden couldn't mask the cloying odor of rot, which made the horse's large nostrils flare. Death had come and gone, but its scent had left its impression on the land, in the air.

Death was scary. The horse much preferred the smell of sugar. Or pralines.

The black horse waited, and Lisabeth Lewis, the new incarnation of Famine, dreamed of fields of dust.

"Famine?" Tammy said, reaching for another cookie. "Like the disease?"

"Is it a disease? I thought it's a condition," Lisa said, putting a third pan into the oven. The kitchen was heavy with the aroma of freshly baked cookies, and Lisa's growling stomach was currently duking it out with her salivary glands to see which part of her body would be more embarrassing. She was practically foaming at the mouth as she imagined the taste of a cookie crumb nestled on her tongue, evaporating slowly as her saliva broke the bit down—but then a particularly loud whine from her middle region ruined the daydream and put the contest in the tank for her belly.

Stupid body.

She slammed the oven door shut and mopped a mitted hand over her brow. The blast of oven heat, though brief, had been blissful. God, she felt like she'd never be warm again. Even her turtleneck sweater wasn't enough to block away the chill.

"Pregnancy is a condition," Tammy said after she finished her cookie. "Famine's a disease."

"So wouldn't that make it Pestilence?"

"No, that's like for bugs. You know, West Nile virus, black plague fleas, swine flu."

"Pigs aren't bugs."

"Same thing," Tammy insisted. "Pestilence is animals. Famine is people. It's a disease."

Lisa didn't want to argue, not with Tammy. She never argued with Tammy. She pulled off her oven mitts and set them on the counter, next to the mixing bowl still a quarter full of batter. "Whatever. But yeah, I was Famine. I had these scales, too. You know, the old-fashioned ones, like you see in legal seals and things."

"Cool."

"I guess." When Lisa had woken up late that morning, she'd looked at her nightstand, convinced she'd see a bronze balance perched there. But no; there had only been her mostly empty water glass and her small alarm clock.

"It is. It's ironic." Tammy was in Lisa's English lit class, where they were studying parody and satire, so she spoke from authority. "You've got a sense of humor when you dream."

"What do you mean?"

"You, as Famine. It's funny. I'm getting more milk."

"It's stupid, is what it is," Lisa said, spooning out more cookie dough onto a baking sheet. She'd made too much, even for Tammy's appetite; she'd have to give some to James later, and a few to her father. Maybe she'd even leave some for her mom for when she returned tomorrow night—or not. "It's not like I don't care about other people, or global hunger, or anything like that. I care." She was, in fact, in three social awareness groups in school. Granted, her mother had strong-armed her into joining to beef up her college applications, and Lisa was a member of those groups in name only. But it still proved that she cared—at least, on paper.

"Of course you do," Tammy said, pouring a second glass of milk. "You're one of the most sensitive people I know."

"So why would I come up with Famine?"

"Like I said, your subconscious has a sense of humor. I mean, Famine? You? You never eat junk food. You exercise everyday."

She did. Multiple times per day. Lisa stood a little straighter as she slapped raw dough onto the cookie tray.

"That's not Famine," Tammy continued. "That's like the opposite of Famine. You're healthy."

Unbidden, Lisa remembered the last words Suzanne had said to her—Suzanne, her so-called best friend, her one-time childhood pal. Last week, Suzanne hadn't said Lisa was healthy. No, Suzanne had called her a name, basically telling her she was a mental case.

"

You need help," Suzanne tells her.

"

I don't!

"

"

You're sick, Leese. Don't you see that?

"

"

You're crazy!" Lisa clamps her hands over her ears, but that doesn't stop her from hearing the last thing Suzanne has to say, the words shaky and broken with tears:

"

You're anorexic, Lisa.

"

Lisa pressed her lips together, surprised by a rush of anger as foreign as it was brief. The feeling ebbed, vanished, leaving behind a dull ache, a pang of loss. She had food issues. She knew that. But she wasn't anorexic. That was ridiculous.

You're not skinny enough to be anorexic

, the Thin voice whispered.

If you were anorexic, your belly wouldn't still pook out over the top of your jeans.

Lisa imagined her fingers tracing over the curve of her abdomen, made all the more prominent by the low-rise jeans she wore. And yes, her lower belly did still pook out.

Anorexics don't have muffin tops

, the Thin voice said.

You're not anorexic. You're just fat.

And she was. No matter how much weight she lost, Lisa would always be fat. She just knew it. She also knew the thought should make her feel sad, or mad, or ... well,

something.

But she didn't feel anything inside, except maybe scooped out. Hollow.

Lisa grimaced, concentrating on scraping the last of the dough from the sides of the glass mixing bowl. Suzanne was insane. Jealous. She wasn't a real friend, not like Tammy.

"If my subconscious was trying to twist things around," Lisa said, "wouldn't it focus on how fat I was? It wouldn't be about taking food away from other people." The very notion made Lisa shudder. "Me being Famine is just dumb."

"It was a

dream

, Leese. What's the big deal?"

Lisa floundered, trying to properly frame her outrage. "Famine hurts lots of people. Famine's a bad guy."