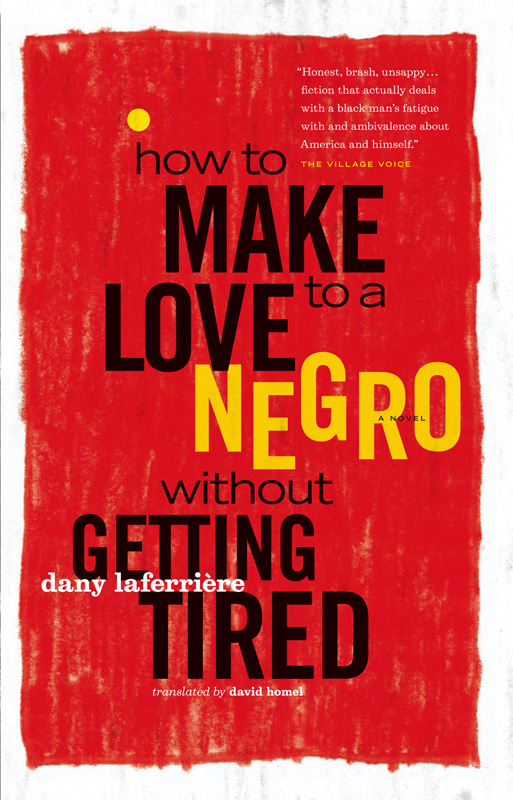

How to Make Love to a Negro without Getting Tired

Read How to Make Love to a Negro without Getting Tired Online

Authors: Dany Laferrière

Tags: #FIC000000

PRAISE FOR

How to Make Love to a Negro without Getting Tired

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“Laferrière brilliantly and hilariously sifts through the tired, frigid beliefs Western culture lays on African-derived males (and everyone else) . . . The 117 pages of

How to

form a heady meditation, a psychic tussle that resonates with the furious stuff in James Baldwin's essays, or Louis Armstrong's smiling trumpet, or Martin Luther King's oratory. . . honest, brash, unsappy, new: non-fiction fiction that actually deals with a black man's fatigue with and ambivalence about America and himself.”

The Village Voice

“A funny book fun to read and original in style and conception.”

Times Literary Supplement

“There's a ribald high energy here, a go-for-broke chutzpah that makes other Canadian writing seem anemic and genteel by comparison . . . Laferrière's book crackles and snaps with the profane and profound power of Jack Kerouac, Henry Miller, Eldridge Cleaver, James Baldwin and Charles Bukowski.”

The Edmonton Journal

“Laferrière's prose is uncompromising. His observation is wicked and sharp. He takes no prisoners, least of all himself.”

The Irish Press

“I can't remember a book that had me laughing and thinking at the same time like this one does.”

Le Devoir

“Dany Laferrière's short novel has a terrorist side to it. Watch out! It's no sputtering firecracker. It's a little grenade, designed by a conscientious, clever demolitions expert.”

La Presse

“Laferrière is totally without respect for any kind of sexual morality.”

Le Nouvelliste

“The book is calculated to offend both blacks and whites, but most readers will forgive the brash writer. No matter how discomfiting his satire, he is always outrageously funny.”

Hamilton Spectator

HOW TO MAKE LOVE TO A NEGRO

WITHOUT GETTING TIRED

dany laferrière

translated by

david homel

how to

MAKE LOVE

Copyright © 1985, 2010 by Dany Laferrière

Translation copyright © 1987, 2010 David Homel

First U.S. edition 2010

10 11 12 13 14 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright license, visit

www.accesscopyright.ca

or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Douglas & McIntyre

An imprint of D&M Publishers Inc.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver

BC

Canada

V

5

T

4

S

7

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN

978-1-55365-585-5 (

B

pbk.)

ISBN

978-1-55365-650-0 (ebook)

Cover and text design by Peter Cocking

Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens

Text pages printed on acid-free,

FSC

-certified, 100% post-consumer paper

Distributed in the U.S. by Publishers Group West

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

Contents

How to Make Love with the Reader. . . Slyly

The Great Mandala of the Western World

Beelzebub, Lord of the Flies, Lives Upstairs

The Negro Is of the Vegetable Kingdom

Must I Tell Her That a Slum Is Not a Salon?

And Now Miz Literature Is Giving Me Some Kind of Blow Job

Miz Afternoon on Her Radiant Bicycle

A Remington 22 That Belonged to Chester Himes

A Bouquet of Lilacs Sparkling with Rain

Like a Flower Blossoming at the End of My Black Rod

A Young Black Montreal Writer Puts James Baldwin out to Pasture

Miz Clockwork Orange's Electronic Rhythm Drowning out Black Congas

A Description of My Room at 3670 Rue St-Denis

Miz Snob Plays a Tune from India Song

Miz Mystic Flying back from Tibet

The Black Poet Dreams of Buggering an Old Stalinist on the Nevsky Prospect

The Black Penis and the Demoralization of the Western World

The West Has Stopped Caring about Sex, That's Why It Tries to Debase It

My Old Remington Kicks Up Its Heels While Whistling Oh Dem Watermelons

You're Not Born Black, You Get That Way

How to Make Love with

the Reader. . . Slyly

“WHEN MY BOOK

came out,” Dany Laferrière recalls with bitterness and amazement, “nobody believed it was written by a black man. They said, Whoever wrote it writes

almost

like a black. Everyone was so sure it was written by a white. A black couldn't write like

that,

they said.”

But the famous photo of Dany sitting in the Carré St-Louis, in his Miller/Bukowski attitude with gym shoes, typewriter and booze-in-a-bag, left the doubters no way out: the Negro of the title was indeed black.

Why did so many readers doubt the narrator's identity, even after he had revealed his true colors? After all, these same readers were acquainted with black writers rising up to take a stand. The names of some of them are mentioned in this novel as icons, some of which are worn out, others still powerful: James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Chester Himes. But what confounded the expectations of Laferrière's unsuspecting readers was this erotico-satiric novel with the come-on title that plays both sides of racial and sexual stereotypes against the middle, and takes fatal and uproarious aim at all manner of sacred cowsâincluding young gifted black writers. Here was a novel by a black man that begins by pronouncing a funeral elegy for the myth of the Great Black Lover. And when Laferrière describes himself and his brothers, he uses the word nègreâ “Negro,” or even “nigger”âinstead of the more politically and socially correct

noir

â“black.” What kind of Nègre was this anyway? Not one whom readers, white or black, had met before.

When the novel hit bookstore shelves in Montreal in the fall of 1985, it caused a sensation. Laferrière's ambiguity, and the difficulty of pinning him down, was one of the reasons his book was so infuriatingâand so seductive.

Laferrière, meanwhile, was simply following the great tradition of satire, giving students of authorial intention a giant headache. Example: readers on the Left of the political spectrum were condemning this novel for not taking a clear enough stand against racism, even as they recommended it to friends. One critic went after Laferrière for making all his white women English-speaking, not realizing the stereotypical value such things might have for a recent immigrant from Haiti: White = English = America. As Laferrière says in one chapter, “America is a totality.”

Laferrière knows about the totality of America from the underside. Born in Port-au-Prince, he practiced journalism under Duvalier. When a colleague with whom he was working on a story was found murdered by the roadside, Laferrière took the hint and went into exile in Canada. The year was 1978. He did what most immigrants do: start at the bottom. He worked tanning cowhides in a Montreal factory.

How to Make Love to a Negro

was begun around this time, and when the narrator says at the end of the novel that this book is “My only chance,” we can see where he's coming from. That manic energy, that bold and sometimes outrageous tone is that of a man eager to get out of the factory and get some respect, a man suffocating in his social position the way the main character suffocates in his overheated room at 3670 rue St-Denis. Some immigrants get to the top through commerce of varying sorts. Laferrière, a voracious reader, understands the lesson of the great Jewish-American writers: you can get to the top with words too.

On one level,

How to Make Love to a Negro

is a book about one man's progress as an immigrant. It is, as Leferrière has remarked, the story of a young man who has acquired a culture he was never meant to have; he covets that culture, he wants you to know he's acquired it (hence, punning literary allusions such as the title of Chapter One), but he doesn't want to lose his identity in the meantime. That's where Laferrière parts company with many immigrant novels: the narrator has a distinctly critical eye on the new culture around him, even as he is trying to move into it. Which is another source of ambiguity in the book.

Just as knowing how to manipulate words gets you social mobility, so does making love.

Voilà :

the eternal marriage of sex and artistic creation. The coupling of white women and black man creates a lot of sparks in this book: the attraction of opposites, the potency of guilt, the weight of history. In one episode, the hero of the piece contemplates the Empire-style family portraits on the wall of an ivy-clad dwelling. What am I doing in such a mansion? he wonders, then answers his own question: I am here to take the daughter of the house to bed. Though nothing in his upbringing prepared him for such a cross-class encounter, he is astute enough to note, “History hasn't always been good to us, but we can always use it as an aphrodisiac.”

Despite the effective teaser title, in this book sex is mostly an indicator of class, ethnic, and historical conflict. When the hero fails to score, it is because he has committed, not a romantic, but a historical gaffe. Whether it is his praise of carbohydrates to a Scarsdale Diet girl, or his admission that, in his country, people eat cats, the results are hilarious and usually result in the hero sprinting out of his prospective lover's apartment to try to catch the last subway of the night. Even in the most sensual moments, the hero's calm, collected consciousness is evaluating the acts of love-making in terms of class and color. I suspect that this attitude, more than any erotic description, led that critic in a Trois-Rivières paper to pontificate that Laferrière “was totally without respect for sexual morality.”