How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself (9 page)

Read How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself Online

Authors: Robert Paul Smith

BOOK: How to Do Nothing with Nobody All Alone by Yourself

5.18Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Let's say you find another kid, and either show him how to get a horse chestnut and thread it on a string, or let him get his own string and lend him a chestnut to start with.

You choose up for who goes first. The one who loses holds the end of his string with the horse chestnut dangling

down. Say you've won the choosing up: you take the end of your string in one hand, the chestnut in the other. (All through this book, I've been saying right hand and left hand, but since a lot of you are left-handed, I'm just going to say one hand or the other from here on. When I was a kid I was left-handed, and now I'm more or less right-handed, so I know how confusing it can be.) The idea is to swing your killer down so it hits the other kid's. It may take you a while to get the idea, but it's not hard to do.

down. Say you've won the choosing up: you take the end of your string in one hand, the chestnut in the other. (All through this book, I've been saying right hand and left hand, but since a lot of you are left-handed, I'm just going to say one hand or the other from here on. When I was a kid I was left-handed, and now I'm more or less right-handed, so I know how confusing it can be.) The idea is to swing your killer down so it hits the other kid's. It may take you a while to get the idea, but it's not hard to do.

Then you hold up your killer and he gets a shot at yours. The idea is to break his killer. After a certain number of shots, you'll see a crack in his killer, or in yours, or in both. You keep on until one breaks, so that it can no longer stay on the string. Sometimes it happens that you bust your own killer in hitting his; that still means you lose. The kid who has the killer left on the string, no matter how it happens, is the winner. That's the game. Now if your killer breaks his, it's a one-killer. If it breaks another one of his, or one of another kid's, it's a two-killer, and so on.

I can't be sure about this next part, but I think that if a one-killer busted a six-killer, it then became a seven-killer. All I can remember for sure is that once I had a forty-killer.

HTDN_72

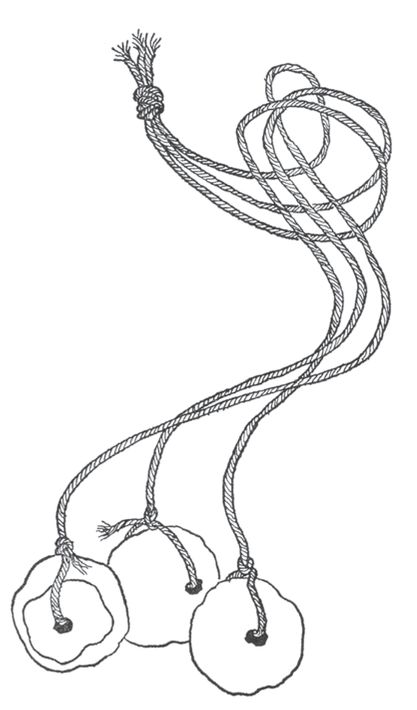

If you get tired of this game, and still have some horse chestnuts left, you can make what we called

bolas

. That's a Spanish word, and Mitch read somewhere that in Argentina, instead of a lasso, the gauchos, the Argentine

cowboys, used

bolas

. Theirs are made of rawhide and metal balls, but we made ours of horse chestnuts and string. You get three horse chestnuts and fasten each one of them to a string, oh, about two feet long. Put the string through and tie it on around so that the horse chestnuts will stay at the end of the string. Now take the other ends of the string and tie them all together.

bolas

. That's a Spanish word, and Mitch read somewhere that in Argentina, instead of a lasso, the gauchos, the Argentine

cowboys, used

bolas

. Theirs are made of rawhide and metal balls, but we made ours of horse chestnuts and string. You get three horse chestnuts and fasten each one of them to a string, oh, about two feet long. Put the string through and tie it on around so that the horse chestnuts will stay at the end of the string. Now take the other ends of the string and tie them all together.

Now, if you will take this by one horse chestnut and whirl it around your head and let it go so that it's aiming at a tree, when you hit the tree with any of the horse chestnuts the string will wrap around and so will the other horse chestnuts. The gauchos used them to wrap around the legs of cattle to hold them, instead of a lasso. What animals you use them on is your affair.

Â

Â

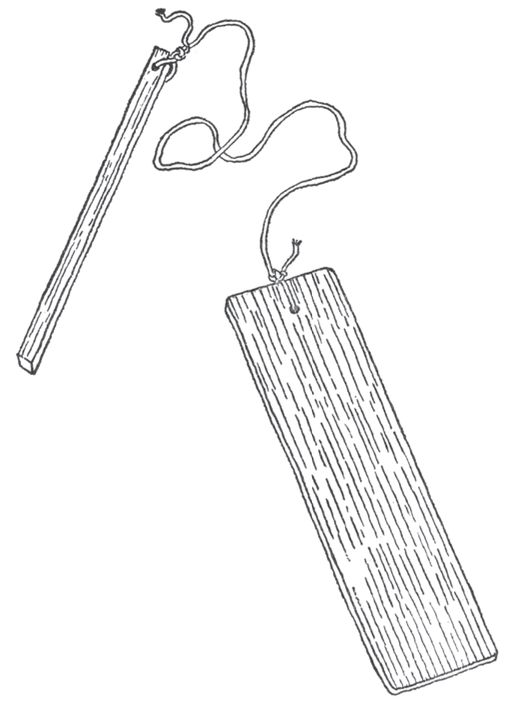

I'm not sure that we called these next things bull-roarers when we made them as kids, but I've since found out that's what they're called. I've also found out that they make them in many parts of the world, and in some primitive tribes, they're used by the grownups to scare devils away. We just used them to make enough noise to drive grownups away.

These are a cinch to make. You need two pieces of wood and a piece of string. It really doesn't matter what

size you make these either, but a good size to start with is one piece of wood about a foot long and half an inch square, another piece about two and a half inches wide, six inches long and a quarter of an inch thick. The first piece is just to be used as a handle, so make it any size that will fit your hand. The other piece has to be thin, but if it's a

little

more or less than a quarter-inch thick, it doesn't make any difference. All you do is bore a hole in one end of the handle, and in the middle of the end of the flat piece. Thread a piece of string about six inches long through the hole in the handle, and tie a good hard knot so it won't come through. Do the same thing with the other end of the string, through the hole in the flat piece. That's the whole thing, all the making you have to do.

size you make these either, but a good size to start with is one piece of wood about a foot long and half an inch square, another piece about two and a half inches wide, six inches long and a quarter of an inch thick. The first piece is just to be used as a handle, so make it any size that will fit your hand. The other piece has to be thin, but if it's a

little

more or less than a quarter-inch thick, it doesn't make any difference. All you do is bore a hole in one end of the handle, and in the middle of the end of the flat piece. Thread a piece of string about six inches long through the hole in the handle, and tie a good hard knot so it won't come through. Do the same thing with the other end of the string, through the hole in the flat piece. That's the whole thing, all the making you have to do.

HTDN_74

Now, whirl it around, holding it by the end of the handle, and when it gets going fast enough, the flat piece will whirl from the air hitting it, and it will start making a wonderful noise. It will work even better if you make both sides of the thin piece taper to an edge, like a knife blade. Whirl it faster and the noise gets higher, whirl it slower and the noise gets lower. You have now learned, even if you don't know it yet, something about the science of physics. I won't tell you what it is, but later on, when you study science, or right now, if you are studying science, you'll find out. The reason I won't tell you is because if I don't, maybe you'll go to your library again and get out a

book about elementary physics, and that'll be one other nothing you can do with nobody.

book about elementary physics, and that'll be one other nothing you can do with nobody.

Â

Â

You probably have seen or heard of boomerangs; they were invented by another primitive people, in Australia, and everybody thinks that what a boomerang is is a thing that you throw and it comes back to you. The fact of the matter is that what the Australian natives did mostly was make bent sticks that they could throw to hit game with, and the idea of it coming back to them was found out, like all great discoveries, by accident. Much later on, they started making them deliberately to come back, and the boomerangs that you see now are just for sport, for fun. You can buy them in a store, they make them of wood and, I understand, now, of plastic. I owned a wooden one when I grew up: a friend of mine gave me one for a present, and I took it along with me on a vacation. One day my wife and I walked out into a big open field; I had no belief I could throw it and make it come back to me, and I told my wife we'd better get ready for a long hike across the field to pick it up, and then I rared back and threw it. It went an awful long ways, and I was just saying to my wife, “You see, I never believed they really work,” when all of a sudden I

heard a whistling noise, looked up, and ducked out of the way just in time to see the boomerang stick in the ground about three inches from where my foot had just been. I was immediately convinced that I was a natural born boomeranger, or whatever they call them. I rared back and let fly again. It didn't come back. I had a nice long walk across the field. I rared back again. Same thing. I never did get it to work that well again.

heard a whistling noise, looked up, and ducked out of the way just in time to see the boomerang stick in the ground about three inches from where my foot had just been. I was immediately convinced that I was a natural born boomeranger, or whatever they call them. I rared back and let fly again. It didn't come back. I had a nice long walk across the field. I rared back again. Same thing. I never did get it to work that well again.

But when we were kids, we never made that kind of boomerang. In the past couple of years, there have been articles in magazines and maybe in some books, about how to make that kind, but I think it's quite a job, unless you're really good at woodworking. If you want that kind of boomerang, maybe your shop teacher can help you out.

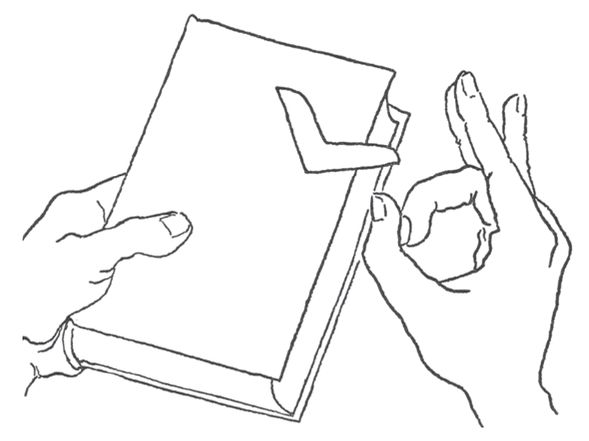

In the meantime, here are two different kinds that are easy to make. One is an indoor boomerang. Okay, now you're sure that I have gone completely goofy, but that's what I mean. An indoor boomerang. Get a piece of very thin cardboard. If your father uses business cards, that's exactly the right kind of cardboard, and the right size. The top flap of a matchbook will do, too. Now just cut a boomerang shape out of it, just about the same size and shape

as in the drawing. Now put it on a book, so that one arm sticks out just a little bit.

as in the drawing. Now put it on a book, so that one arm sticks out just a little bit.

HTDN_77

Flick it with your fingernail and it'll go sailing out just like an Australian boomerang, and after very little practice, you'll find out how to make it whirl so that it will come back to you. A good way to do it is to hold the book in one hand, tipped up a little, so that the boomerang goes up in the air at an angle, and slides back at just about the same angle, like a ball going almost to the top of a hill, and then rolling down again.

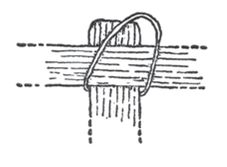

The other kind of boomerang is for use outdoors, and all you need for it is two long strips of thin wood, about the size of a regular twelve-inch ruler. Balsa wood, that you can get at a hobby shop, is good for this, but any light, thin wood is good, like the sides of an orange crate, which you can pick up for free at the grocer's or the supermarket. All you do is make a cross of the two pieces, and fasten them together with a small rubber band. A good way to do this is to put the rubber band on one piece, a little way from the top.

HTDN_78a

Cross the other piece over, between the rubber band and the end of the first piece, then pull the rubber band up over the second piece and around and under the first piece.

HTDN_78b

As always, if the rubber band is too long, double it.

HTDN_79a

Other books

Catalyst (Forevermore, Book Two) by K.A. Poe

The Escapement by K. J. Parker

Medicine Wheel by Ron Schwab

Netherworld: Drop Dead Sexy by Tracy St.John

A Cowboy in Disguise by Victoria Ashe

From London Far by Michael Innes

Jet by Russell Blake

Thirty Days: Part One by Belle Brooks

Phantom Warriors: Arctos by Jordan Summers