How They Started (2 page)

Authors: David Lester

Sara Blakely: putting her butt on the line

Founder:

Sara Blakely

Age of founder:

29

Background:

Fax machine sales, stand-up comedy

Founded in:

2000

Headquarters:

Atlanta, Georgia

Business type:

Men’s and women’s intimate apparel

In 1998, Sara Blakely was a 27-year-old, bubbly blonde

aspiring lawyer whose day job was selling fax machines. Then one day, she didn’t like how she looked in a pair of white pants.

Her handcrafted solution would revolutionize the stodgy women’s shapewear category, which hadn’t changed much since Playtex introduced its first rubber girdle in 1940. Sara’s comfortable support undergarments were designed for real women’s figures and marketed with a sassy attitude previously unheard of in women’s lingerie. Launching her product in the strangely male-dominated women’s underwear category would take two years and require scores of prototypes, a brazen shared bathroom visit, and a little help from a red backpack.

Sara would later chalk it all up to failing the Law School Admission Test (LSAT). The Florida State University graduate had always wanted to be a lawyer like her father; however, her failing LSAT scores would ultimately point her in a different direction.

The Clearwater, Florida, native drove to Disney World in hopes of getting a job playing Goofy, but learned that at 5’6” she was too short. She was offered the role of a chipmunk, but decided to forgo the hot costume for a job selling fax machines door-to-door instead.

Seven years later, she was at a convention for top-selling fax-machine sales reps. She recalls one motivational speaker at the event giving a speech on how there are no bad products. “I’ll prove it in four words—Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles!” he shouted. She would think of this speech again a few years later, when she got a product idea of her own.

The trouble began with an expensive pair of chic, cream-colored pants Sara bought in 1998. They sat in her closet, seldom worn, because she felt they made her rear end look a bit lumpy. She had a nice pair of open-toed shoes they would work with, but hesitated to wear the outfit. She realized she probably needed some kind of support undergarment to give the pants a smooth line, but was certainly not about to wear a girdle.

“Traditional shapers were too thick and left lines and bulges, and underwear leaves a panty line,” she says. “And thongs, I’ll never get—they put the underwear exactly where we have always been trying to get it out of.”

In a moment of inspiration, Sara took out a pair of scissors and cut the feet off a pair of her support pantyhose. Voila! Her pants looked great, and she still had the naked-foot look she wanted for the shoes. She went to a party in Atlanta’s trendy Buckhead neighborhood that night, feeling fabulous. There was one problem—the cut-off bottoms of the pantyhose kept rolling up her legs all night. Sara thought if she could find a way to keep the legs from rolling up, she’d have a great product.

“Traditional shapers were too thick and left lines and bulges, and underwear leaves a panty line,” she says. “And thongs, I’ll never get …”

Little did she know it would be a two-year sojourn from that “Ah-ha!” moment to getting a finished, packaged product ready for sale.

In her quest to become a successful inventor, Sara was armed with little but an engaging smile and a passionate belief that she had created something women would find supremely useful. She’d never taken a business class in college, had no experience in fashion merchandising and certainly had zero insight into hosiery manufacturing.

Knowing she’d need a manufacturer to create a prototype of her product, she began looking up hosiery mills in the phone book. She discovered the product-sourcing platform thomasnet.com, which listed all the manufacturers in the US. From there, she learned that there were a lot of hosiery manufacturers located fairly nearby in North Carolina. Over the course of about six months, Sara cold-called all the hosiery makers and asked if they would be interested in making her prototypes. Every single one said no.

Pressing on, Sara decided to prototype her garment herself while she continued seeking a manufacturer. She stocked up on sewing supplies at Michael’s and other local craft and fabric stores and started sewing. Soon, she had a design that offered the control-top support of typical pantyhose but stopped just below the knee, assuring a smooth line down a woman’s thigh.

Over the course of about six months, Sara cold-called all the hosiery makers and asked if they would be interested in making her prototypes. Every single one said no.

As she worked on her prototype, she decided she needed to patent her invention. She looked up three of the top law firms in Atlanta, and made appointments. For her presentations to the lawyers, she brought her product and printed materials in a very special container—her lucky red backpack from college.

To say the lawyers were not impressed with Sara’s idea would be an understatement. One kept looking around the room while she pitched her product. He later confessed he found her idea so ridiculous that he suspected he was being filmed for a

Candid Camera

-type reality TV show.

All the lawyers quoted Sara upwards of $5,000 to handle her patent paperwork. Since $5,000 was the total savings she had in her bank account, that wasn’t going to work. Instead, Sara headed to Barnes & Noble, got a book on how to write a patent application, and started drafting. She researched hosiery patents at night in the Georgia Tech library.

Sara made a list of nearby hosiery and shapewear manufacturers and embarked on a road trip, once again bringing along her lucky red backpack. For several weeks, she drove around, meeting plant managers in person. They were invariably male.

The conversation followed a similar track at each stop. The plant owner would begin by asking, “And you are … ?”

“Sara Blakely,” she would reply.

“And you’re with … ?” they’d ask.

“Sara Blakely,” she’d say, smiling wider.

“And you are financially backed by … ?” they’d return.

Smiling even wider, Sara would say, “Sara Blakely.”

At each stop, after this exchange, Sara was gently shown to the door.

“So nice to meet you,” the owner would say. “Best of luck with your idea.”

But the road trip wasn’t a total loss. On plant tours, Sara learned a lot about how women’s undergarments were made. She learned how various yarns could be combined to give a garment different characteristics.

Two things she saw on the tour would shape her company’s approach to the business. First, she saw that to save money, most manufacturers utilized one average-sized elastic on all their products’ sizes.

Second, she discovered that the manufacturers all used hard-plastic forms of women’s bodies to test their garments. Now she knew why so many women’s undergarments didn’t fit well: small and large sizes didn’t have the right-sized waistbands, and real women never tried on the products before they hit stores.

Sara saw how to stand out in the market: her product would be customized to fit different sizes and be tested on real women.

“They’d put the underwear on the form,” Sara recalls, “and then these men would stand back with their clipboards and say, ‘Yep, that’s a medium.’”

Immediately, Sara saw how to stand out in the market: her product would be customized to fit different sizes and be tested on real women.

Several weeks after Sara’s road tour, she got a call from one manufacturer she’d visited in Charlotte, North Carolina. He informed her that he had decided to help her make her “crazy” product.

“What made you change your mind?” Sara inquired.

He responded with: “I have two daughters.”

From the start, Sara knew she needed a fabulous, attention-getting name for her product. But it took more than a year to come up with one.

She wanted to incorporate a “K” sound. She knew two of the most recognizable brands were Kodak and Coca-Cola, and both had a strong “K” sound. Also, from stand-up comedy, she knew it was a trade secret that the “K” sound can make people laugh. Suddenly, driving through Atlanta traffic, the name hit her: she would call her sassy new undergarment Spanks.

“The word came to me, like it was written across the windshield of my car, and I pulled over to the side of the road and wrote it down,” Sara says.

At the last minute, she changed the spelling to SPANX, as she knew it was difficult to trademark real words. The “X” gave her the “K” sound she wanted while forming a unique, new word and it signaled what the product did: help women make their butts look better.

Up to this point, Sara had not told anyone but lawyers and manufacturers about her invention. She didn’t want to risk hearing any negative feedback about it.

“A great idea is most vulnerable at the moment you have it,” she says. “Something just told me intuitively to keep it inside. I had a year under my belt before I said, ‘OK everyone, it’s footless pantyhose.’ And of course they all looked at me like ‘Are you crazy?’ But if you’re a user of your product and you know it works, then just stick with it, and find the people who will help you get it made.”

Heartened to have a manufacturer on board, Sara moved to complete her patent application. She recruited her artistic mother to make a sketch of her wearing the product to submit on the application. The final step was to decide what legal claims the product would make in its packaging and marketing.

For this touchy area, she went back to the

Candid Camera

lawyer and asked if he would help. He still didn’t understand her idea, but he told her for $700 he was willing to spend a weekend on it. The attorney asked to speak to her manufacturer to get the garment’s technical specifications.

The manufacturer was Southern with a deep accent. When the attorney asked what the garment was made of, he replied, “Cotton and lacquer.” The attorney duly noted this and completed the application.

That night, Sara couldn’t sleep. She planned to file her patent application the next day. She kept wondering: how was there lacquer in the product? The next day, she called the manufacturer back.

“Ted, can you spell lacquer for me?” she asked.

“Shore,” he drawled. “L-y-c-r-a.”

With the lacquer mystery solved, the application was quicky changed and sent on its way. For $300, Sara trademarked her name on the US Patent Office’s website, and for $150 incorporated her business name.

The next step was to design the packaging for

Spanx

. Sara toured hosiery departments in big stores and noticed the department was a sea of beige and gray. Every package looked identical, down to the same photo of a half-naked model. She knew she wanted her packaging to have a completely different look, so that if she could land shelf space with a big retailer, SPANX would immediately stand out. Also, she had no money for advertising, so the package essentially would

be

the ad.

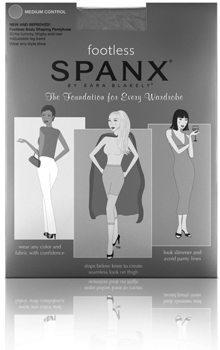

“I chose red, which was extremely unconventional,” she recalls. “Then, I put on three cartoon-illustrated women who were very different-looking. No one had done that, either.”

The original footless SPANX packaging.

She worked on her design nights and weekends for three months on a friend’s computer, while working days at her fax-sales job. Her goal was to make the package look like a present a woman would buy for herself, rather than a commodity women dread buying. To write the package copy, she bought 10 different pairs of pantyhose and read the packages. Whatever language they had in common Sara concluded must be needed for legal reasons, so she added it to her package.