How the Hot Dog Found Its Bun (12 page)

Read How the Hot Dog Found Its Bun Online

Authors: Josh Chetwynd

Tags: #food fiction, #Foodies, #trivia buffs, #food facts, #History

Why the fizzy sweet became such a magnet for fictional stories is unclear. Heck, it didn’t even have the Internet to spread false rumors. But the danger claims did frustrate Mitchell, who in 1979 took the unusual step of writing open letters to parents and schools about the safety of Pop Rocks (which were also known as Cosmic Candy). Mitchell even addressed the Mikey rumor, telling customers that “we checked on ‘Mikey’s’ well-being and found he is alive and well.”

Popsicles: Cold night and forgetful kid

All Frank Epperson wanted was a cool drink. On a red-letter date (now lost in the mists of time) in 1905, he was sitting on his back porch using a stick to mix together some dry flavored powder into a glass of soda water. For one reason or another, he became distracted. This shouldn’t be surprising because Epperson was just eleven years old at the time. Maybe his mother called him; maybe he went to play some ball; or, maybe he simply lost interest in the drink, which by some accounts had lost its fizz.

Whatever the case may be, when he was called into the house that evening he left the mixture outside. It would have been a forgotten mistake if not for the fact that it was an unexpectedly ultrafrigid evening that night in Northern California’s Bay Area where Epperson grew up. The next day he came out to find his drink frozen with the stirring stick poking out.

Epperson tasted the combination and loved it. But what was an eleven-year-old to do? He apparently showed his friends (I’m sure it made him very popular at recess), but basically put the idea in the freezer—so to speak.

He would go on to serve as a pilot in World War I and embark on a number of business ventures from real estate to manufacturing kewpie dolls. But in the early 1920s, he noticed that ice-cream sandwiches were becoming a popular treat.

While frozen fruit juice treats, called “hokeypokeys,” had been around since the 1870s with vendors successfully selling them on the streets of New York and other big cities, Epperson figured his creative advantage would be that stirring stick he’d left in his soda mixture as a preteen. He filed for a patent for “a handled, frozen confection” in 1923 and began selling his treat, which he first called “the Epsicle”—a combo of his last name and icicle—at a popular local amusement area called Idora Park in Oakland. (Useless fun fact: The wood of choice for the ice treat’s stick was and remains birch.) It was a hit and he sold the rights to make his ice lollies to a New York manufacturer called the Joe Lowe Company.

One of the first orders of business around the time Epperson partnered with Joe Lowe was to alter the product’s name for marketing purposes. The most popular story surrounding the choice of “Popsicle” asserted that Epperson’s children called it “pop’s icicle” rather than its real name. This was no small marketing sample as he had nine kids, so this tale could very well be true. Others suggest that the name was simply a variation on another sweet that used a stick: the lollipop.

Regardless, the product quickly became a nationwide favorite and by 1928, sixty million of the treats were sold. With royalties rolling in, Epperson’s childhood discovery looked to be an annuity for life. Sadly, the Depression changed that course. Being an entrepreneur at heart and always in need of money for his next venture, he ended up selling his stake in his invention in 1929.

Little did he know that during the Depression, a double-Popsicle with two sticks, which allowed friends to break apart the ice treat and share the cooling confection for very little cost, would become an even bigger hit and cemented the Popsicle’s place in most Americans’ memories of childhood. (In one 2005 survey adults said that the Popsicle—rather than the ice-cream cone or the ice-cream sandwich—was the treat they most often purchased as a child.)

Later in life Epperson, who died in 1983 at age eighty-nine, would have mixed emotions about his accidental discovery. On the one hand, he clearly regretted his decision to sell out. “I was flat and had to liquidate all my assets,” he once said. “I haven’t been the same since.” But he did always appreciate his place in snack lore—which undoubtedly made him a hit with his more than two dozen grandchildren. “It has given a lot of simple pleasure to a lot of people,” he said in 1973 on the fiftieth anniversary of the Popsicle. “And I’ve enjoyed being part of it all.”

Potato Chips: Take-no-guff chef

Sussing out the origins of the potato chip can be as messy as digging your hand into a bag of the ubiquitous snack food.

For decades one particular story has been the darling of most authors, journalists, and potato chip industry professionals. It revolves around a larger-than-life chef from Saratoga Springs, New York, named George Crum. The son of an African-American father and a Native American mother, Crum was renowned as a top-notch cook in the fancy resort town in upstate New York. During his career, he would serve such luminaries as presidents Chester A. Arthur and Grover Cleveland.

In 1853 Crum was working as the head chef at one of the area’s most exclusive hotels, Moon’s Lake House. On one summer evening, a prominent guest—some claimed it was the uber-wealthy Cornelius Vanderbilt—ordered french-fried potatoes. Back then these thick-cut slices of the starchy tuber were a dish of the rich. Thomas Jefferson discovered them while serving as ambassador to France in the 1700s and brought them back to the United States, offering the potatoes to company at Monticello. On the night in question, the guest (whether it be Vanderbilt or another well-heeled patron) thought the potatoes were either too soggy or not flavorful enough for consumption and sent them back to the kitchen.

Even when it came to the well-heeled and famous, Crum was not a man to be trifled with. It was said that he once forced industry barons William Vanderbilt and Jay Gould to wait more than an hour while other guests who had arrived earlier got seated first. Crum was clear about his skills: He could cook a dinner “fit for a king,” but if there was a complaint he could also present “the most indigestible substitutes [he] could contrive.”

In this case, the complaint from the dining room meant that he was going to provide what he thought would be the latter. He sliced the potatoes so thin that when fried they would come out too crispy to pick up with a fork. He then added so much salt that there could be no complaint about it being bland. The tale concludes with the guest trying Crum’s attempt at indigestible and loving it. From then on, the dish—named Saratoga Chips—was included on the menu as a house special.

As great as this story is, there is some evidence it’s more legend than reality. While most everyone agrees that the chip did find its start in Saratoga Springs, Crum may have only been a bit player in its invention—and the tale of battling a rich eater apocryphal. Author Dirk Burhans offers a compelling case on this front in his book

Crunch! A History of the Great American Potato Chip

. Burhans points out that while Crum was not a man short on confidence, he never claimed he came up with potato chips. In fact, that contention didn’t really enter print until the 1940s. As for the upset customer anecdote, it didn’t become popular until the 1970s.

Still, even if Crum’s lucky run-in with a snotty guest isn’t true, it’s quite possible that the potato chip was an accidental find. Burhans suggests that the “most credible” origins explanation did come from the kitchen of Moon’s Lake House. But it was Crum’s sister, Katie Speck Wicks, who made the discovery. “Aunt Katie,” wrote Burhans, “was frying crullers and peeling potatoes at the same time. A thin slice of potato found its way into the frying oil for the crullers, and Katie fished it out.” Crum saw the chip, took a taste, and was pleased. After Katie explained how it happened, Crum supposedly said, “That’s a good accident. We’ll have plenty of these.” While Crum’s local obituary in 1914 didn’t mention the chip, Katie’s obit three years later credited her with its creation.

Other explanations exist as well. Still, the popular disgruntled patron story has never been definitively disproved, leaving some hope that Crum’s tale of trying to stick it to the rich man may have truly happened.

Pretzels: Holy rewards

If author Dan Brown ever needs new grist for a

Da Vinci Code

–type book, he might consider munching on some pretzels. The snack has Catholic roots shrouded in the fog of food lore.

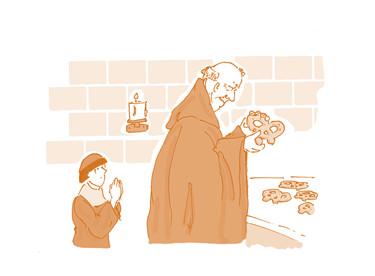

One popular story about the pretzel’s religious invention stars a monk in either Northern Italy or Southern France (already we’re getting a bit hazy). It was circa AD 610 and the religious man’s job was making bread. One day, he had excess dough after completing his work and wasn’t sure what to do with it. Giving it just a moment’s thought, he decided to roll the dough into a new shape to make gifts for small children who had successfully learned their prayers. The pretzel’s distinctive design was meant to represent two folded arms. Back then folding arms, rather than clasping or putting hands together, was the common posture for praying. The monk allegedly dubbed his creation the

pretiola

, which is Latin for “little reward.”

An alternative to the story ditches the monk and has the dawn of pretzels occurring approximately two centuries earlier. In this one, Roman Christians, who abstained from meat and dairy products during the forty days of Lent, needed a nonoffending food option. The pretzel was made to serve that role and, again, the shape was to remind religious adherents to focus on prayer. The original name in this account was

bracellae

(Latin for “little arms”). According to the Catholic Education Resource Center, there is a fifth century illustration of a pretzel-like product in the Vatican Library but no recipe to corroborate this early birth (for those of you who want to get on this mystery, check out Codex 3867).

While those are the most popular tales, others exist. There’s one that says monks made the strangely shaped bread to allow for pilgrims to easily hang it on their walking staffs. An alternative claims a German king decreed loaves of bread be made in a way to allow the sun to shine through them three different ways. Why he wanted this is unclear. Whichever you believe, the pretzel was a popular purchase at the local marketplace in Germany by the Middle Ages. At that point it was known by an Old High German word,

bretzitella,

and then

brezel

(or

bretzel

, depending on who you believe) before transforming into its modern name.

The Christian storytelling surrounding the pretzel doesn’t end there. It’s said that pretzels saved Vienna from Muslim invaders in 1529. The Ottoman Turks were laying siege to the European capital and devised a plan to dig tunnels underneath the sturdy city walls in the middle of the night. What the Turks didn’t know was bakers labored through the night cooking pretzels in order to have fresh bread ready for morning customers. These men supposedly heard the below-ground commotion and alerted authorities. As a result, the Turks were repelled, preventing Muslim rule in Europe.

This romantic recounting is very unlikely. It’s true that the Ottomans tried to tunnel under the walls in order to lay mines to destroy the city’s protection, but, according to the book

Besieged: An Encyclopedia of Great Sieges from Ancient Times to the Present

, it was an Ottoman deserter who warned the Austrians about the digging plans.

So what ties between the pretzel and the Christian faith are worthy of our devotion? Some in Europe, along with members of the Pennsylvania Dutch in the United States, have put pretzels on Christmas trees as decorations and hidden them as prizes at Easter (a la Easter eggs). They have also been used at wedding ceremonies, where the baked good is broken apart in a wishbone-like game. As for the rest of it, I leave it to Dan Brown to figure out how to weave it all together in

The

Pretzel Code

.

Twinkies: Strawberry afterthought

Devoted fans of the ubiquitous Twinkie should give praise to the ever-so-wholesome strawberry for the confection’s invention. It was the strawberry’s relatively short season for freshness that inspired the spongy American icon.

In 1930 James Dewar was working as a Hostess bakery manager in Schiller Park, Illinois, a Chicago suburb. Times were tight and the company wanted to come up with a low-priced product that would appeal to Depression-starved consumers. Cue the strawberry. Dewar’s factory used them as part of a little finger cake product they were selling. But the problem was strawberries would only stay sweet for six weeks so the cakes came and went quickly. As a result, the bakery molds used for the strawberry treats sat idle for most of the year.