How Does Aspirin Find a Headache? (6 page)

Read How Does Aspirin Find a Headache? Online

Authors: David Feldman

Who would have ever thought of Lewis Carroll summarizing the answers to an Imponderable, while simultaneously contemplating the plight of a Sears portrait photographer?

Submitted by Donald McGurk of West Springfield, Massachusetts. Thanks also to Wendy Gessel of Hudson, Ohio, and Geoff Rizzie of Cypress, California

.

Why

Are Carpenter’s Pencils Square?

Two reasons. Carl Reichenbach, product manager at pencil giant Dixon-Ticonderoga, told

Imponderables

that the square shape enables carpenters to draw thin or thick lines more easily than with conventional pencils.

But a more pressing point: If we drop a pencil from our desk, it’s not a big deal to lean over and pick it up from the floor. However, what if we happen to drop a pencil from a beam on the thirty-fourth floor of a construction site? Or the roof of a home? As Ellen B. Carson of Empire Berol USA put it, “The carpenters’ pencils are produced in a square shape so they won’t roll off building materials.”

Submitted by Nate Woodward of Seattle, Washington

.

Why

Don’t Windshield Wipers in Buses Work in Tandem Like Auto Wipers?

Hearing that two

Imponderables

readers were obsessed with this question made us feel less lonely. We’ve always wondered whether we were the only ones bugged by the infernal racket and displeasing look of two huge, awkward, asymmetrical windshield wipers churning away on rainy trips.

The answer turns out to be simple, if technical. Most automobiles use one motor to power two windshield wipers. With bigger windshields and blades, the two bus wipers are driven by separate, independent motors, so the movement of the two blades is not coordinated.

Isn’t there any way to get the two wipers to work together? Sure, for a cost, as Karen Finkel, executive director of the National School Transportation Association, explains:

A larger motor to accommodate the larger blade and windshield could be developed. However, there isn’t a reason to synchronize the wipers so it hasn’t been done.

Hmmm. Not driving us nuts, we guess, isn’t reason enough to change the status quo.

Submitted by P.M. Cook of Lake Stephens, Washington. Thanks also to Karyn Heckman of Greenville, Pennsylvania

.

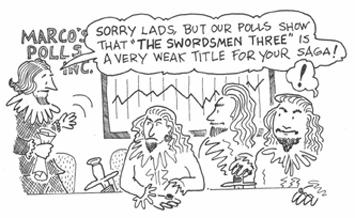

The Three Swordsmen

sounds like a decent enough title for a book, if not an inspiring name for a candy bar, so why did Dumas choose

The Three Musketeers?

Dumas based his novel on

Memoirs of Monsieur D’Artagnan

, a fictionalized account of “Captain-Lieutenant of the First Company of the King’s Musketeers.” Yes, there really was a company of musketeers in France in the seventeenth century.

Formed in 1622, the company’s main function was to serve as bodyguard for the King (Louis XIII) during peacetime. During wars, the musketeers were dispatched to fight in the infantry or cavalry; but at the palace, they were the

corps d’élite.

Although they were young (mostly seventeen to twenty years of age), all had prior experience in the military and were of aristocratic ancestry.

According to Dumas translator Lord Sudley, when the musketeers were formed, they “had just been armed with the new flintlock, muzzle-loading muskets,” a precursor to modern rifles. Unfortunately, the musket, although powerful enough to pierce any armor of its day, was also extremely cumbersome. As long as eight feet, and the weight of two bowling balls, they were too unwieldy to be carried by horsemen. The musket was so awkward that it could not be shot accurately while resting on the shoulder, so musketeers used a fork rest to steady the weapon. Eventually, the “musketeers” were rendered musketless and relied on newfangled pistols and trusty old swords.

Just think of how muskets would have slowed down the derring-do of the three amigos. It’s not easy, for example, to slash a sword-brandishing villain while dangling from a chandelier, if one has a musket on one’s back.

Submitted by John Bigus of Orion, Illinois

.

Why

Don’t Public Schools Teach First Aid and CPR Techniques?

Wouldn’t our world be a safer place if every high school required students to take a class in life-saving techniques? Reader Charles Myers sure thought so, so we tried to find out why CPR isn’t a part of school-room curriculums in most communities. Considering the violence in our schools, the argument needn’t be made that such training would only be usable in the “outside world.” In fact, this issue recently has become a hot topic among educators, particularly because of concerns about the response times of fire, paramedic, police, and other emergency medical services in many communities.

All of the health officials we contacted felt that CPR and first aid training in public schools could be valuable, but they provided a litany of reasons why we shouldn’t expect to see it in the near future. Why not?

1.

Money

. Most school systems are riddled with financial problems. CPR training is labor-intensive. While a normal classroom might have a ratio of twenty-five or thirty students per teacher, CPR requires a six-to-one or eight-to-one radio. And training teachers to learn and then teach CPR costs money.

2.

Liability problems

. “America,” says Bill Powell, prehospital emergency training coordinator for Booth Memorial Medical Center in Flushing, New York, “is the land of the suing.” What if a student botches a rescue operation? Would the school be legally and financially liable for poor training?

3.

No one should be forced to administer CPR

. Several of our sources indicated that although it is an admirable goal to have every student learn first aid techniques, in practice it might not be a good idea to force those who don’t desire to learn or who are incapable of administering them properly. Georgeanne Del Canto, director of health services for the Brooklyn, New York, Board of Education, told

Imponderables

that good intentions notwithstanding, asking every student to learn first aid would be a little like asking every schoolkid to go out for the wrestling team: Too many students would be insufficiently strong, energetic, or limber to apply CPR adequately, and more than a few would be too squeamish.

If we required all students to learn CPR, we would be forcing them to learn a technique that they would not be obligated to use outside of school. In most states, Bill Powell told us, lay citizens are under no legal obligation to act as a Good Samaritan (in most states, physicians do have such an duty), even in life-threatening situations.

4.

Motivation of students

. Powell isn’t too sanguine about the desire of students to learn CPR properly. Why should they pay any more attention to first aid training than they do to math or history? Most non-health professional students in CPR courses are people who are friends or family of someone who they fear is at risk; few learn CPR out of sheer altruism or an abstract academic interest.

5.

Time

. CPR certifications must be renewed every two years, not so much because first aid techniques change but because most students, thankfully, never get a chance to apply their lessons in real life. Constant retraining of students might be another financial and labor drain on schools, although this problem could be ameliorated by introducing the subject in the junior year of high school, thus saddling colleges with the task of recertification.

6.

Training of trainers

. “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing,” emphasizes Ira Schwartz, project director of the New York State Regents Advisory Committee on Community Involvement. Schwartz and others we talked to thought that finding a ready supply of teachers qualified to teach CPR, or training nonqualified teachers to do so, was a major hurdle.

7.

Competition

. CPR isn’t the only health item clamoring to be included in public school curriculums. Although she joined in the chorus of educators who thought that universal CPR training would be a noble idea, Arlene Sheffield, director of the school health demonstration program for the New York State Education Department, told us that many educators believe that teaching students about bulimia, anorexia nervosa, and child abuse has a higher priority. Sheffield’s program, for example, focuses on eliminating drug abuse among students, a subject of more pressing importance to students, educators, and parents than CPR. As Sheffield puts it,

The pool of money and time available for schooling in any given subject is finite and CPR and first aid have a lot of healthy competition.

CPR training is not totally abandoned in our public schools. Many schools offer kids training on an elective basis; community groups and hospitals offer low-cost courses. And a few public school systems, such as Seattle’s, find the time, money, and training resources to offer all students CPR courses.

Charles Myers was not alone in wondering if some of that time he (and, let us admit, we) wasted in school might have been better spend learning a skill that could save others’ lives. When we asked Emmanuel M. Goldman, former publisher of

Curriculum Review

, this Imponderable, he echoed our sentiments exactly:

As to why CPR isn’t taught, at least in high school: It beats me. Probably because it is such a logical, desirable, and useful skill.

Submitted by Charles Myers of Ronkonkoma, New York.

Why

Do Peanuts in the Shell Usually Grow in Pairs?

Botany 101. A peanut is not a nut but a legume, closer biologically to a pea or a bean than a walnut or pecan. Each ovary of the plant usually releases one seed per pod, and all normal shells contain more than one ovary.