House on the Lagoon

Read House on the Lagoon Online

Authors: Rosario Ferré

A Novel

Rosario Ferré

I wish to thank both Susan Bergholz and John Glusman for their generous help during the writing of this book. Their literary expertise and spiritual support were crucial to me, and made this novel possible. I also wish to thank my husband, Agustín Costa, for sharing the novel’s difficult moments with me, as well as its joys.

1

Buenaventura’s Freshwater Spring

2

Buenaventura Arrives on the Island

4

When Shadows Roamed the Island

Part 2 The First House on the Lagoon

10

Madeleine and Arístides’s Marriage

11

The Courage of Valentina Monfort

Part 4 The Country House in Guaynabo

15

Carmita and Carlos’s Elopement

Part 5 The House on Aurora Street

Part 6 The Second House on the Lagoon

22

A Dirge for Esmeralda Márquez

Part 7 The Third House on the Lagoon

38

The Strike at Global Imports

Part 8 When the Shades Draw Near

40

Petra’s Voyage to the Underworld

41

Quintín Offers to Make a Deal

Any shade to whom you give access to

the blood will hold rational speech

with you, while those whom you

reject will leave you and retire.

HOMER

The Odyssey,

XI

Before I ever loved a woman

I wagered my heart on chance

and violence won it over.

JOSE EUSTASIO RIVERA

The Vortex

M

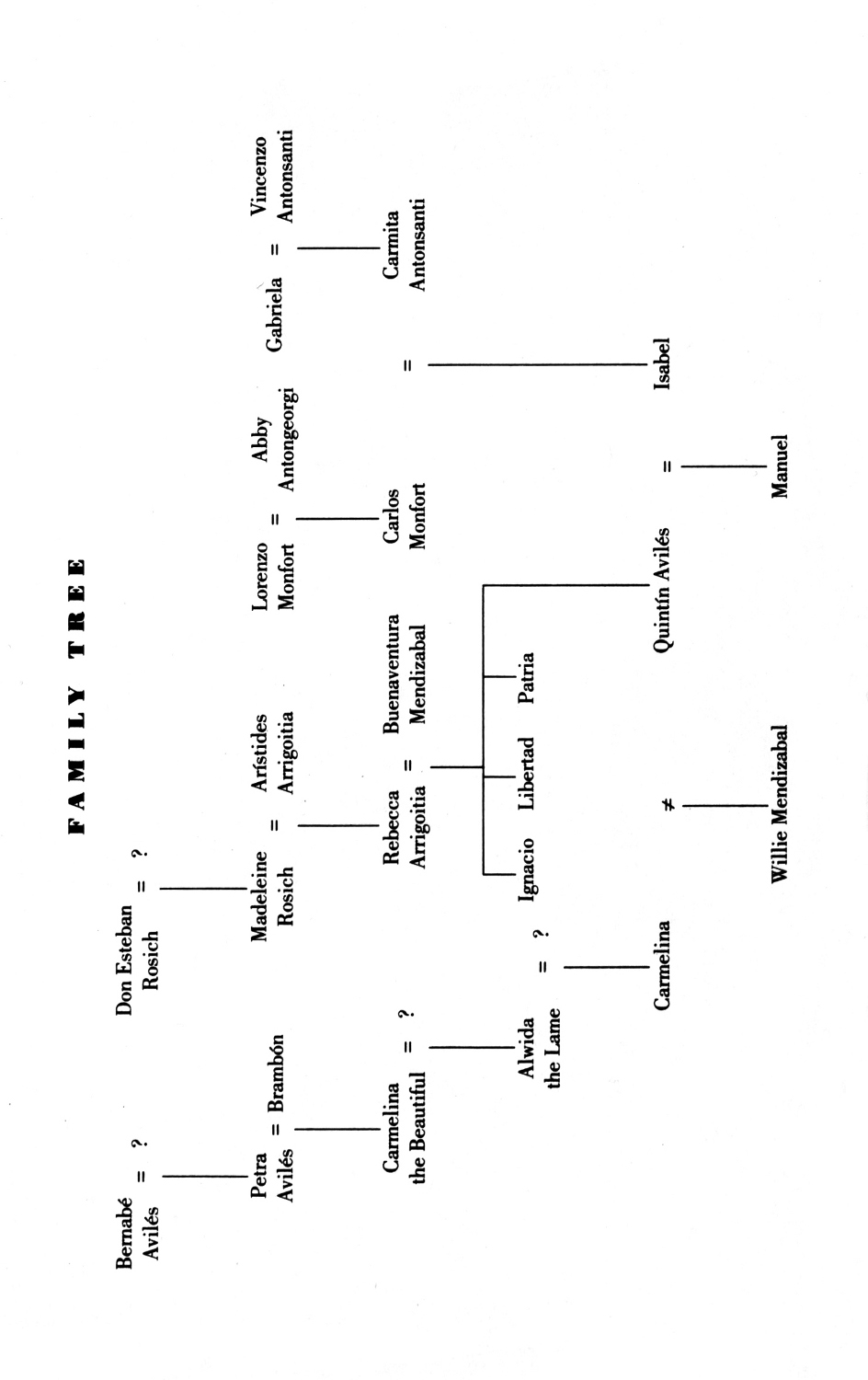

Y GRANDMOTHER ALWAYS INSISTED

that when people fall in love they should look closely at what the family of the betrothed is like, because one never marries the bridegroom alone but also his parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, and the whole damned tangle of the ancestral line. I refused to believe her even after what happened when Quintín and I were still engaged.

One evening Quintín came to visit me at the house in Ponce. We had been lounging on the veranda’s sofa, when a sixteen-year-old boy who was sitting on the sidewalk in front of the house began to sing me a love ballad.

The singer, the son of a well-known local family, had been secretly in love with me, although we had never met. He had seen me occasionally when our paths crossed in the streets of Ponce and at parties. Recently, my picture had been in the society columns, announcing my engagement to Quintín Mendizabal.

The young man became very depressed when he read the news, and in his deranged state the only thing that would ease his sadness was to sit under the flowering oak tree which grew in front of my house on Aurora Street and sing

Love Me Always

in a haunting tenor voice.

That night, as I sat next to Quintín on the veranda’s sofa, I was mesmerized by the song. I had never heard anyone sing with such a voice; it sounded like a silver bell as it filtered through the terrace’s white iron grillwork, and I thought that if there were angels in heaven, they would probably sing like that.

When the unexpected serenade began, Quintín had one of his fits of temper, which he inherited from his ancestors. He rose from the sofa, walked unhurriedly to the door, crossed the garden path under the purple bougainvillea vine massed over the veranda’s roof, went through the hedge of hibiscus that grew in front of the house, his belt in his hand, and mercilessly lashed the unfortunate bard. I ran after him crying, but I couldn’t make him stop. When she heard my cries for help, Grandmother ran out of the house, too, and tried to hang on to Quintín’s arm, but he went on beating the boy. Abby and I stood there horrified. As the brass buckle whistled at the end of Quintín’s belt, he coldly counted the blows aloud, one by one.

I had begged the boy to get up and defend himself, but he refused even so much as to look at his attacker. He went on sitting on the ground, singing: “Love me always, / sweet love of my life. / You know I’ll always adore you. / Only the memory of your kisses / will ease my suffering,” until he fell unconscious on the sidewalk.

Soon after this, the young man slashed his wrists with a razor blade, without even trying to contact me. I was tormented by guilt, and for a while deeply resented Quintín for his brutal behavior. Many years later I still couldn’t listen to that song without tears welling up in my eyes. It always made me remember the young man who had wanted to serenade me, spreading the balm of his voice on a beautiful summer night.

It took my family a long time to recover. From then on, Grandmother was obstinately opposed to my marriage to Quintín Mendizabal. “Someday you’ll be sorry, that’s all I can tell you,” she said to me repeatedly. “There are enough kind, educated men in this world so that you shouldn’t have to end up in the arms of a common bully.”

Abby had married a Frenchman’s son, and this perhaps had

s

omething to do with her dislike for everything Spanish. “Quintín’s ancestors,” she would insist, “are from the most backward country on earth. ‘Spain never had a political or an industrial revolution,’ my husband used to say, and it’s been our tragedy that it was the Spaniards who colonized us. If I ever travel to Europe, the only reason I would visit that country would be to relieve myself, and then I’d leave.”

For years the episode stayed vividly in my mind, though at the time I refused to see it as a bad omen. I never forgot the unhappy singer, however. Whenever I thought of him, I remembered what Grandmother had said. Unfortunately, I did not mind Abby’s advice, and on June 4, 1955, I walked down the aisle on Quintín’s arm.

Quintín was very much in love with me. After the young man’s suicide, he began to have trouble sleeping, and he would wake up in the middle of the night bathed in sweat. One day he came to visit me in anguish and asked me to forgive him. “An ungovernable temper is a detestable thing,” he said. “One ceases to be oneself and becomes another; it’s as if the devil himself crept up under your skin.” He didn’t want to be like his father, his grandfather, or the rest of his ancestors, he added, who were descended from the Spanish Conquistadors. They all had wrathful dispositions and, worse yet, were proud of it, insisting that rashness was a necessary condition for bravery. But there would be no getting away from them if I didn’t help him wrench himself from the morass of heredity.

It was after lunch, the hour of the siesta, and everyone else in the house was sleeping, stretched out lightly on their beds without bothering to take their clothes off. We were sitting as usual on the veranda’s sofa, and the afternoon heat intensified our wooing. We kissed and embraced a dozen times under the flowering jasmine that hid us from intruding eyes. “Love is the only true antidote to violence,” Quintín said to me. “In my family, terrible things have happened which I find difficult to forget.”

It was then that we made our pledge. We promised we would examine carefully the origins of anger in each of our families as if it were a disease, and in this way avoid, during the life we were to share together, the mistakes our forebears had made. The rest of that summer, we spent many afternoons together, holding hands on the veranda and telling each other our family histories as Grandmother came and went busily through the house, performing her household chores.

Years later, when I was living in the house on the lagoon, I began to write down some of those stories. My original purpose was to interweave the woof of my memories with the warp of Quintín’s recollections, but what I finally wrote was something very different.

The Foundations

1

Buenaventura’s Freshwater Spring

W

HEN BUENAVENTURA MENDIZABAL, QUINTÍN’S

father, arrived on the island, he built himself a wooden cottage on the far side of Alamares Lagoon, a forgotten stretch of land that had been only partially cleared of wild vines and thickets. There was a spring nearby which the residents of the area had once used. A stone fountain built around it had been maintained by a caretaker, since it was considered public property. In recent years, however, people had forgotten all about it. The caretaker, an arthritic old man who lived next to the spring, had stopped keeping it up, and soon the mangrove swamp had enveloped it completely.

Half a kilometer down the beach stood the beautiful houses of Alamares, one of the most exclusive suburbs of San Juan. Alamares stood on a strip of land crossed by a palm-crested avenue—Ponce de León Avenue—with water on either side: the Atlantic Ocean to the north, and Alamares Lagoon to the south. The more public side of the avenue looked out to the Atlantic, where the surf was always swelling and battering the sand dunes; and the more private one opened onto the quiet beach of the lagoon. This beach ended in a huge mangrove swamp, and only the tip of it was visible from Alamares. When he moved to the area, Buenaventura built a modest cottage precisely at this site, where the mangrove swamp met the private beach of the lagoon.